I occasionally get away to the desert (like the Sahara, in this photo I took near Zagora, Morrocco), and more often to the forest, in order to escape the overwhelming distraction of noise in the world, and get down to a simpler vision of life.

This is one of the things that has appealed to me most, in making a feature film on the exploration of polar deserts, The Blinding Sea, which is nearing completion.

But the problem is not just noise in the world. Actually, there are times when I feel utterly saturated with metaphors – with those figures of speech that supposedly explain one thing by implying that something else “stands in” for it. Metaphors permeate political discourse, media polemics, advertising, self-promotions, likes on Facebook, analogies, wishful thinking, selective interpretations (cherry-picking), caricature, distortions….

In re-reading the works of the French historian of mentalities Jean Delumeau, particularly La Peur en Occident and Le Péché et la peur, I realize to what extent metaphors have shaped mentalities, channeling people’s fears, whipping up panic about all the evil supposedly lurking within each person, and especially within the other. As if the human dependence on figurative language – on seeking something to “stand in” for whatever dissatisfies or frustrates or frightens – sends people down dark pathways to delusion.

Religion sometimes strikes me as a way of organizing and codifying delusions. Spirituality aims at voluntary simplicity however – at turning down the volume of this ongoing glut of metaphors.

Delumeau shows that fear dominated Western civilization between the 14th and 18th centuries. The fear of the Four Horsemen of the Apocalypse – conquest, war, famine and plague; the fear of fire spreading across cities, the collapse of society and its hollowing-out from within; the fear of sex, sin, aging, disease and death; the fear of the end of the World, the judgment of God; the fear of ourselves.

Delumeau shows that the dominant culture in Europe (ecclesiastical and/or political) singled out several categories of people as agents of Satan, since they seemed to live in flagrant defiance of the panic-stricken European desire for control.

Once the Reformation and Counter-Reformation got underway in the 16th century, Catholics and Protestants accused each other of being agents of Satan. Of course, in identifying agents of Satan, one also claimed to be acting as an agent of God in a supreme combat between good and evil.

Leading figures in early modern Europe readily consigned “idolatrous” Amerindians to the fire, because they refused to convert to Christianity in newly-conquered territories of the New World. Martin Luther was so furious with Jews for not spontaneously converting to his vision of Christianity, he wrote virulent anti-Semitic writings that Adolf Hitler would later distribute in millions of copies in Nazi Germany. Catholic Spain feared and therefore persecuted Muslims.

The largest category of agents of Satan was made up of women (whose biological power and understanding of Nature threatened many men and the celibate priests with whom they formed a kind of unholy alliance). Last of all, Delumeau mentions witches (most often female). He singles out ascetic monks, celibate priests and Reformation pastors as responsible for advocating the contemptus mundi – contempt for the world, and even fuga mundi – flight from the world; for promoting a morbid fascination with the macabre, and the rejection of human sexuality as evil in itself. Which amounts to rejecting Nature.

True, some parts of the New Testament promote the universality of humankind; but other parts overtly promote this delusional fear of the other, which amounts to targeting categories of people, denying them a real existence on their own terms, loading them up with fearful attributes, converting them finally into metaphors.

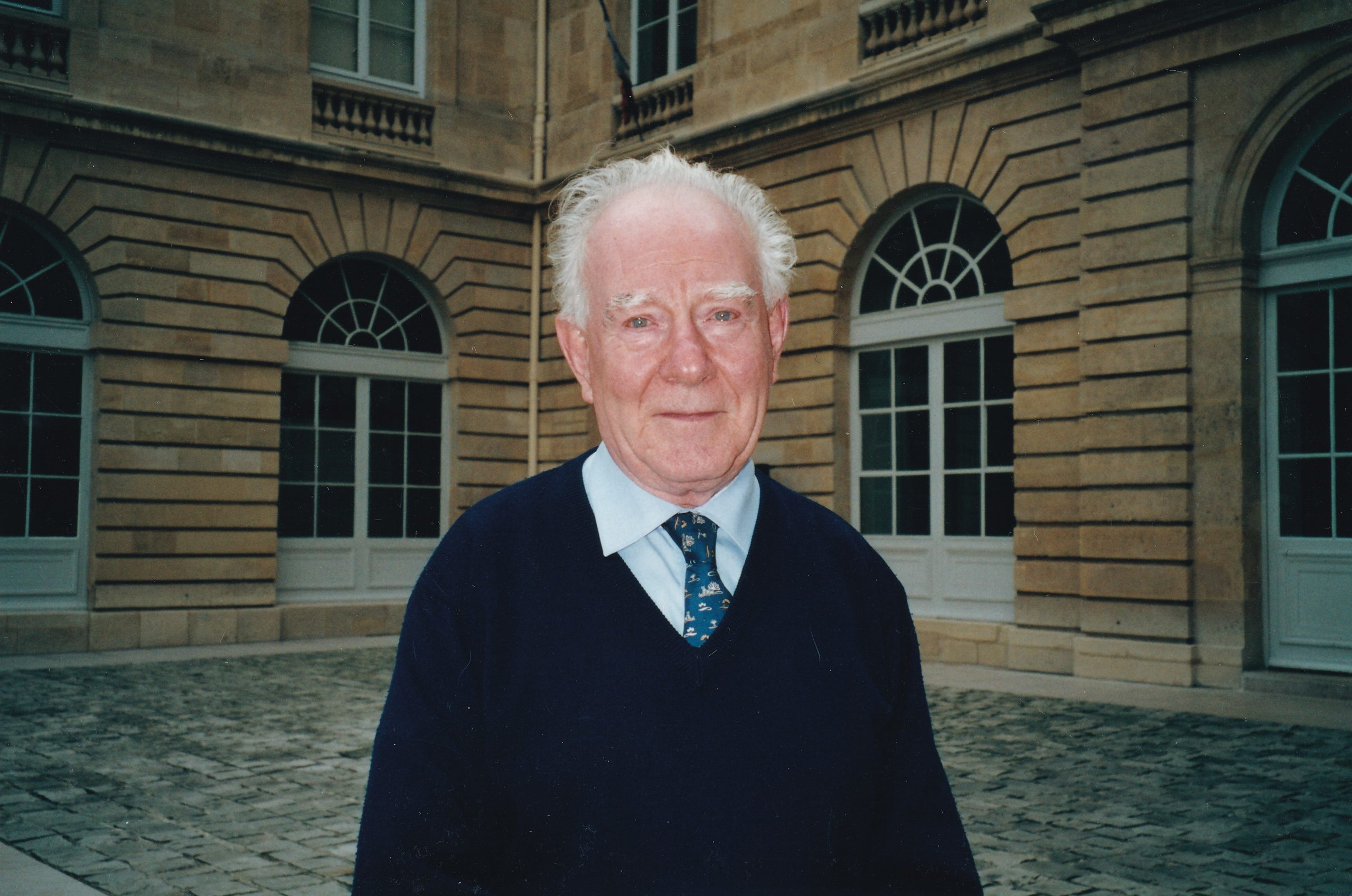

Jean Delumeau died a few weeks ago; of the 15,000 or so interviews I have done, my interview with him at the Collège de France was surely one of the most interesting. Once the interview was done, he told me he remained a practising Catholic, despite all the hostility he had faced from self-appointed guardians of the faith who objected to his study of religion. He mentioned to me how appalled he was by the Catholic Church’s record on pedophile priests. Jean Delumeau struck me as more spiritual than religious. Indeed, the distinction between voluntary simplicity and the quest for power runs like a golden thread through his works.