As I continue reading Des monstres et prodiges (Monsters and Wonders), by Ambroise Paré, I am struck by the way he draws on one authoritative source after the other, between Antiquity and his own 16th century, repeating, citing, reporting, but never calling into question whether all the beasts, freaks, demons and devils his authorities describe could ever possibly have existed. Paré, the father of modern surgery and the Renaissance precursor of evidence-based medicine, relies on myths and hearsay, especially coming from people high in the social hierarchy. But nowhere is there any sign in this work of evidence. Where has it gone? Occasionally he mentions that a monster was presented to the Pope in person, who had the monster in question (that is, the evidence) destroyed forthwith. After all, monsters were sometimes conjured up by demons and devils; they came with a lot of moral baggage; even though he was a Huguenot himself, Paré presents the Pope as the supreme moral arbiter of the age. When Paré justifies the stories he tells by appeals to authority, there is no question of going back and verifying what actually happened.

Des monstres et prodiges is not a work of critical, scientific investigation. It is more of a late medieval bestiary, highlighting subhuman deformities and brutish creatures. This comes as a surprise, considering the intellectual and professional stature of Ambroise Paré, surgeon to three 16th-century kings of France, scientific author and medical innovator.

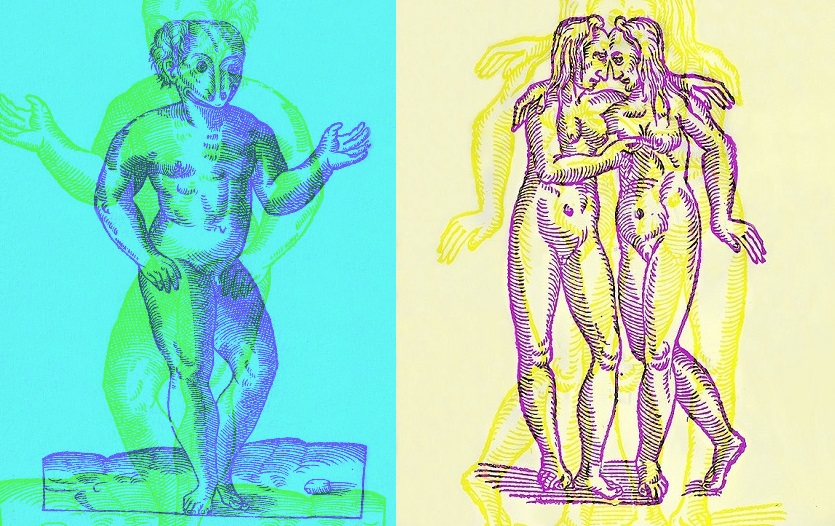

Consider for example how Paré describes the child with a frog head born near Fontainebleau in 1517, shown on the left in the image below: Jean Bellanger, surgeon in the royal artillery of King Francis I, investigated the matter, accompanied by a royal prosecutor and a notary who presumably would know something about evidence. They found that one Magdaleine Sarboucat had suffered from a fever, and on the advice of a friend had held a frog in her hand until it died, upon which she conceived the next day with her husband Esme Petit, and the child was ultimately born with the head of a frog fixed to its body as a result. This is a case of sympathetic magic, by which the fever was first transferred from a woman to a frog, fatally, and then the frog in dying transferred its energy or appearance to the yet-to-be-conceived child. Weird.

Then again, Paré notes that in 1495, Sebastian Münster encountered twin girls conjoined at the forehead in the town of Bürstadt near Worms (on the right in the image above): they lived to the age of ten, but first one twin, then the other twin died. In 1544, Münster published a celebrated scholarly work, the Cosmographia universalis, so Paré must have considered him a credible authority.

As Europe expanded outwards, exploring and exploiting the rest of the world, reports came back from overseas of strange beasts and humans unlike anything Europeans had seen before.

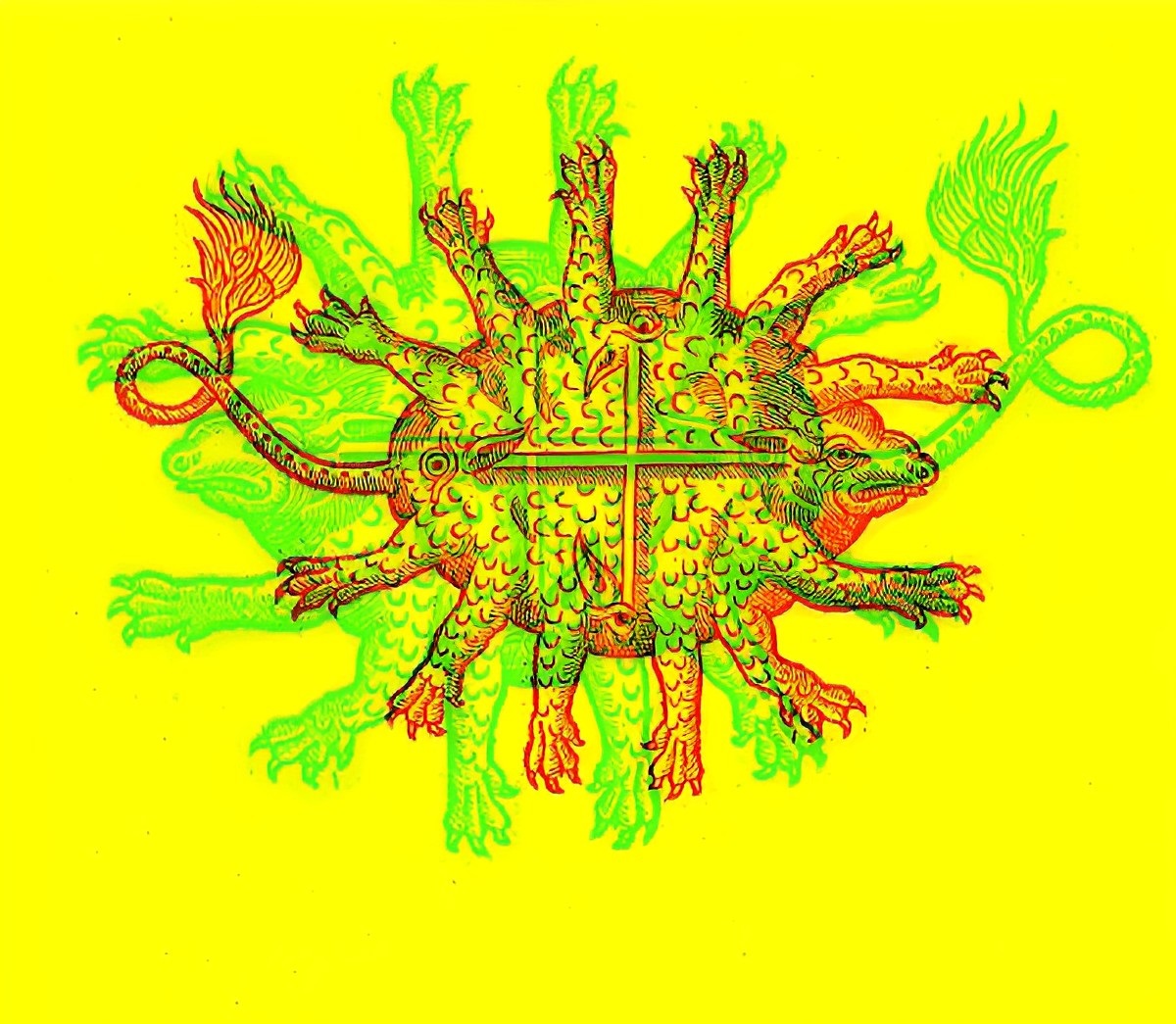

An example is this frightful African monster:

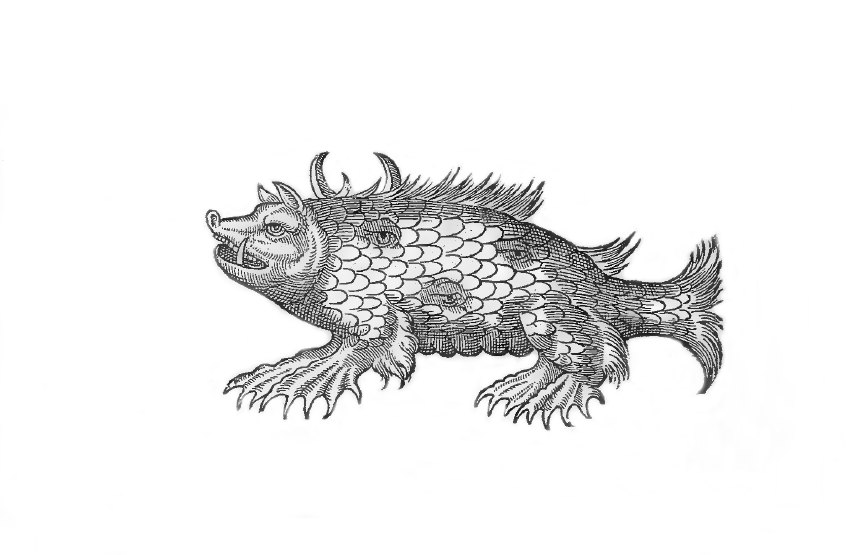

During the Renaissance, the ocean was a storm-racked place of unfathomable terrors and dangers – capricious, insatiable, liable to engulf ships and crews in mountainous waves, and send them to oblivion. No wonder that sea monsters found their way onto many nautical charts of the time. Consider this frightful horned and fanged fish, a Truye marine (literally a sea sow in English), with spiked web feet good for attacking, and eyes not only on its face but also ominously placed here and there along its body:

I doubt this is actually what we today call a sea pig or sea cucumber – a creature that typically lives at depths of over 1,200 to 5,000 metres and would disintegrate if ever it reached the surface.

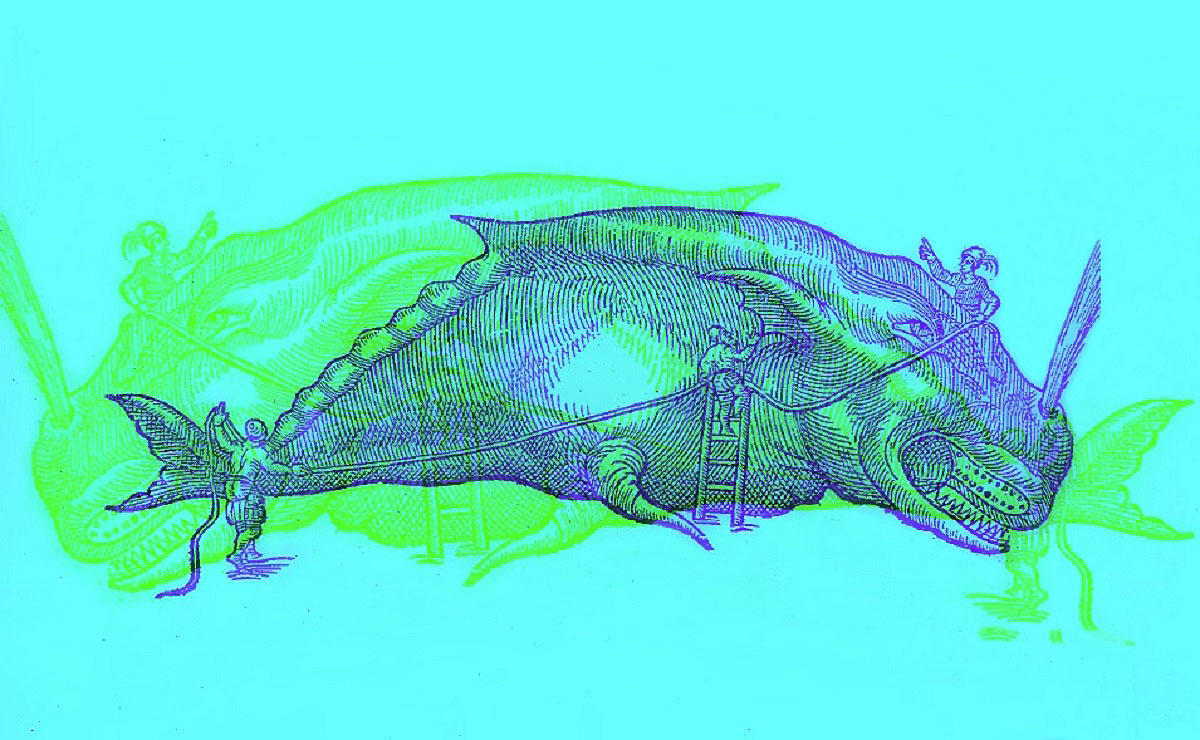

During the Renaissance, the disproportionate relationship of humans with whales was puzzling for European observers, who considered themselves fashioned in the image of God, and therefore superior to all other species. According to the Book of Genesis, on the fourth day of the world “God created the great sea monsters and every living creature that moves, with which the waters swarm, according to their kinds, and every winged bird according to its kind. And God saw that it was good. And God blessed them, saying, Be fruitful and multiply and fill the waters in the seas, and let birds multiply on the earth.” Then on the sixth day God gave humans dominion over the rest of creation: “God said, Let us make man in our image, after our likeness; and let them have dominion over the fish of the sea, and over the birds of the air, and over the cattle, and over all the earth, and over every creeping thing that creeps upon the earth.” But whales were so much greater than humans! Whatever the case, they were a monstrously valuable source of meat and oil.

In representing many different kinds of monsters, Ambroise Paré reminds me of his near-contemporary William Shakespeare, in The Tempest, who often mocks Caliban (an Amerindian on an enchanted island of the New World) as a servant-monster. Trinculo calls Caliban A most scurvy monster … A lying, drunken monster … An abominable monster.

It was convenient and reassuring for Eurocentrists to represent the Other with disregard and scorn as a fearsome, brutish, subhuman monster who deserved to be enslaved and/or cast into the darkness from the outset.

In this work, Ambroise Paré does not show a great deal of understanding. Instead, he draws up a catalogue of thrills, curiosities and exceptions, which serve as a road map of visceral fantasies and fears during the Renaissance.

While Paré is remembered today as a leading figure in the early modern Scientific Revolution, he seems literally to have believed in all the legendary creatures of this ongoing freak show, from elephant-slaying dragons (as in the feature image at the top of this blog) to basilisks, half-human/half-horse aberrations, tritons, hideous sea devils, pigs with human faces and every imaginable variety of conjoined twins and otherwise malformed children.

As if the fabulous creatures and demons in Harry Potter were part and parcel of the canon of scientific knowledge today!

By the way, all of these woodcuts are from Des monstres et prodiges by Ambroise Paré. I have added colour and double exposures to make some of these woodcuts more interesting to look at.