My feature film The Blinding Sea is coming out soon. The final cut of chapters 1 to 5 is done. There remain chapters 6 to 8. The film is destined for educational, non-theatrical distribution.

When I got started, I already knew how to conduct interviews from my 20 years of work for print and broadcasting media. I must have interviewed 15,000 people. But I now had to learn how to use video cameras and record sound properly. In the course of making the film, I upgraded from high definition to 4K although the end-product is 1080p. I threw myself time and again into extreme environments. Forming an accurate picture of what I needed in my mind, and then capturing clean footage and clean sound, was very challenging.

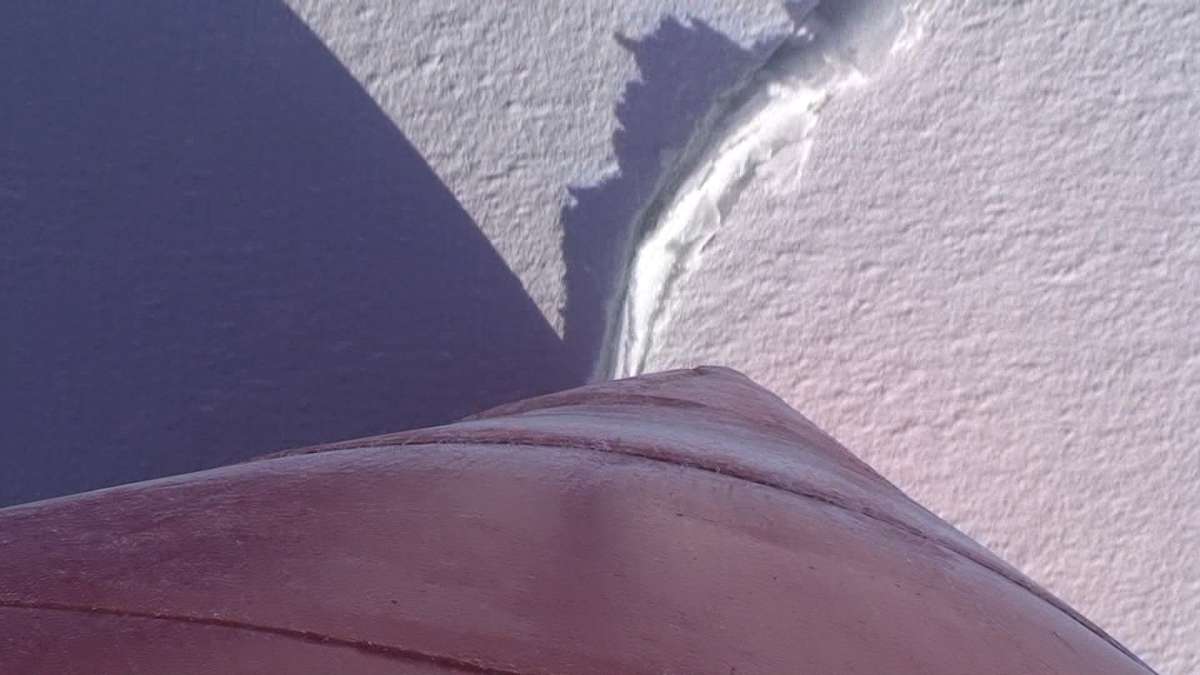

For example on a tall ship tossed this way and that on the Southern Ocean between Patagonia and Antarctica, how should I film the movement of the ship? A movie is after all … a moving picture! But I had never seen such a crazy stretch of sea. Would I get so disoriented by waves rolling along the hull and sometimes up onto the deck that I simply forgot to clean drips of salt water off the lens? What if condensation clouded up my camera, when my mind was distracted? Some other people on board, coming out onto the roller-coaster deck, suddenly vomited out of control. Fortunately I do not get seasick. (The above photo is a screen capture from the top of the foremast on the bark Europa, which I sailed to the Antarctic Peninsula.) If I wanted to represent my own disorientation on video, as part of the story, how best should I do this?

Again, I recall joining the Canadian research icebreaker Amundsen via helicopter in the Beaufort Sea, just next to Banks Island. As the helicopter circled the ship before landing, the Amundsen frozen into endless ice-pack seemed so lonely, so unnatural, so vulnerable, as if marooned at the ends of the Earth. How would I rise to the challenge of filming in air temperatures of -48° C (-54° F), and that was even without factoring in windchill? What if my camera froze while I was a few nautical miles out on the ice? What if I froze? What if marauding polar bears decided to have us for lunch?

Then, once we got underway again, the ship blasted her way through the ice, pulverizing it, sending up bursts of incredibly dry salt spray. This went on for hours at a time, with a banging, booming sound like smashing copper pots and pans together. It set my body throbbing in daytime, and disrupted my sleep at night. But the ice itself fought back, breaking up into symmetrical blocks, by turns roaring and shivering as it clawed its way along the hull, shrieking like some crazed dragon falling from the sky. The deck lurched and shuddered during this onslaught on the ice. It was certainly hard to hold the camera steady, let alone remain standing. How would I film this, without weakening my raw footage with excessive movement? Or was the movement itself an integral part of the story?

Then there came the moment when I accepted this was another world. I no longer resisted the High Arctic. I now fell strangely silent. I remember I was on the bridge at the time, the windows were frosted over, and I could just make out in the dusk, as a downdraft of smoke swirled from the funnel, the name of the ship: the Amundsen.

The Blinding Sea is not simply a Nature film. It is above all about the interactions of people and animals in extreme polar environments, and the quest for understanding and the sharing of knowledge, between different cultures.

One of the greatest moments was going dog-sledding with George Konana in Gjoa Haven, Nunavut in February. The windchill got down to -68.3° C (or -91° F) that day. (George is Inuk, and it is well-known that Inuit resist cold far better than southern Canadians do.) He kidded me after an hour or two, asking why I was so eager to head back inside. Actually my camera had completely frozen, the plasma screen had turned to ooze, the motor was dead, the lens was covered with ice crystals, I had forgotten to bring a backup, and besides I could no longer move my fingers. Well, it was all in a day’s work!