The woodcut at the top of this blog shows Nordic hunters on skis, chasing after reindeer. It is from a famous 16th-century work on the history of the Scandinavians by the Swedish archbishop Olaus Magnus. Thanks to Marie Frenette, for hand-colouring the woodcut.

As I have been putting together my feature film The Blinding Sea, I have been focusing on whether it was necessary, during the heroic era of polar exploration in the late 19th and early 20th centuries, to understand Vitamin C in order to avoid scurvy.

I have come to the conclusion that it was not. Yes, scurvy is a deficiency disease, but knowing about Vitamin C is not required to avoid scurvy, since Vitamin C was only identified in the 1930s, and some people have understood remedies to prevent scurvy for thousands of years.

Two thousand years ago, Chinese navigators grew ginger plants on board their vessels, as a remedy for scurvy.

A thousand years ago, Viking navigators kept barrels of cloud-berries on their dragon-ships, as a remedy for scurvy.

In the 1530s, Iroquoians near modern-day Quebec City showed Jacques Cartier how to cure scurvy by drinking a herbal tea made from white cedar leaves.

In 1555, the Swedish archbishop Olaus Magnus published a compendium of Scandinavian folk knowledge (as well as legends about giants, trolls and demons) going back to Viking days. The woodcut above is from that work. He identifies two remedies for scurvy: drinking herbal tea made from wormwood and eating fresh meat.

In the 1600s, French navigators began using spruce tea to combat scurvy while at sea, and Dutch navigators used fresh lemons and oranges.

Then in the mid-1700s, James Lind published a work about scurvy, in which he recounts conducting a trial with twelve patients with scurvy, on board HMS Salisbury:

“Their cases were as similar as I could have them. They all in general had putrid gums, the spots and lassitude, with weakness of their knees. They lay together in one place, being a proper apartment for the sick in the fore-hold; and had one diet common to all, viz, water-gruel sweetened with sugar in the morning; fresh mutton-broth often times for dinner; at other times puddings, boiled biscuit with sugar, &c.; and for supper, barley and raisins, rice and currents, sago and wine, or the like…. The most sudden and visible good effects were perceived from the use of the oranges and lemons; one of those who had taken them, being at the end of six days fit for duty.… Next to the oranges, I thought the cider had the best effects.”

In 1877, the Scottish physician John Rae, who had spent 25 years working for the Hudson’s Bay Company in Arctic Canada, testified before an Admiralty Committee investigating the causes of scurvy. He explained he had lived through Arctic winters on a diet of fresh meat, without eating any vegetables or fruit. The Admiralty Committee was inquiring above all into the disastrous British Arctic Expedition of 1876-1877, led by Sir George Nares, which had been severely impacted by scurvy. Expedition organizers had sought substitutes for fresh meat, to lighten the loads of man-hauling crewmembers: they had assumed that dehydrating, drying, salting and otherwise processing fresh meat (that is, using industrial processes to create light-weight substitutes) would not destroy the freshness on which human health depended. Dr. Rae was right about the benefits of fresh and lightly cooked meat; expedition organizers were wrong to believe industrial substitutes for fresh meat were healthy.

By the 1890s, Dr. Frederick Cook, the American polar explorer, wondered how Greenland Inuit could possibly understand that eating fresh meat prevented them from getting scurvy: can’t civilized men “learn something from these wild savages?” he asked, in his private diary.

But in the 1890s, alternate views of scurvy were also being promoted, even by the experienced Norwegian polar explorer Fridtjof Nansen, who assumed scurvy was caused by bacteria, not some deficiency of diet.

Robert Falcon Scott definitely suffered from scurvy during the Discovery expedition of 1901-1904, and probably suffered from it during the Terra Nova expedition of 1911-1912, during which he died. He was following dietary advice from the British Admiralty.

The Hungarian biochemist Albert Szent-Györgyi discovered Vitamin C in the 1930s.

The fascinating story of scurvy reveals how Chinese, aboriginal, Scandinavian and even Scottish folk wisdom (based on experimentation by trial and error) was way ahead of the British Admiralty and Western theoretical medicine.

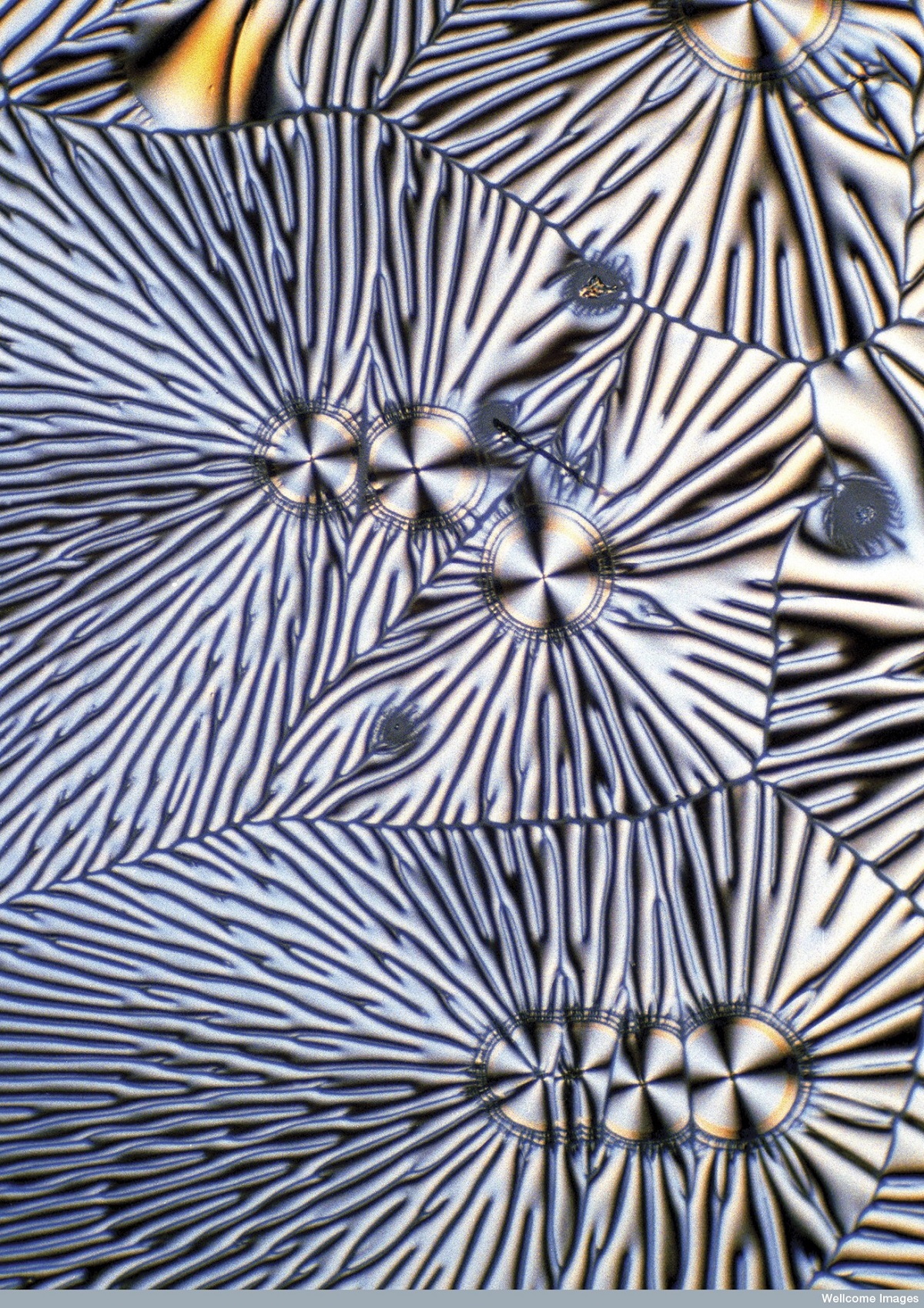

Credit: Kevin Mackenzie, University of Aberdeen. Wellcome Images

images@wellcome.ac.uk

http://wellcomeimages.org

Vitamin C (ascorbic acid) crystals imaged by cross polarised light microscopy. Vitamin C is an antioxidant and is important for collagen formation and wound healing. A good source of vitamin C is found in a variety of fruit and vegetables including citrus friuts, brussels sprouts and broccoli. It is a water soluble vitamin that cannot be stored in the body so needs to be ingested regularly. A lack of Vitamin C causes scurvy. 100X image magnification.

Light microscopy

2006 Published: –

Copyrighted work available under Creative Commons Attribution only licence CC BY 4.0 http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/