As I continue screening The Blinding Sea in Britain, France, Canada and the United States, I find it interesting to hear university critiques of my work. I put an enormous amount of historical and iconographic research into this production, so the similarities between academic research and documentary film-making might seem obvious. I tell audiences that my doctorate in the History and Philosophy of Science has helped shape the way I identify and explore key themes in the film, such as access to Aboriginal knowledge/lack of access to Aboriginal knowledge. So far, so good.

However, there are some big differences between academic research and film-making.

For one thing, a film is in the narrative mode, whereas much academic research is in the logico-deductive mode.

An academic needs to be critical in order to be relevant. I notice in some academic research what I would call the “therefore syndrome,” which consists in interpreting every strand of evidence, drawing conclusions, and abstracting the significance of what is being described.

Whereas, when making a documentary, I am careful not to editorialize, not to moralize, not to judge the characters, whether historical figures like Roald Amundsen or people I interviewed for the film. I find it far more interesting to leave characters a certain latitude, so they can share their point of view, intact, without being interrupted and redefined by my own interpretations. This leaves it to each person in the audience to make up his or her own mind based on the evidence I present.

The “therefore syndrome” raises disturbing questions about the art of documentary. Should a film-maker take a position on every piece of information, coming and going, as if the film were a series of factual claims and refutations? Is a documentary basically an argument, a set of talking points? Why make a film at all, if the film-maker does not come down on one side or other?

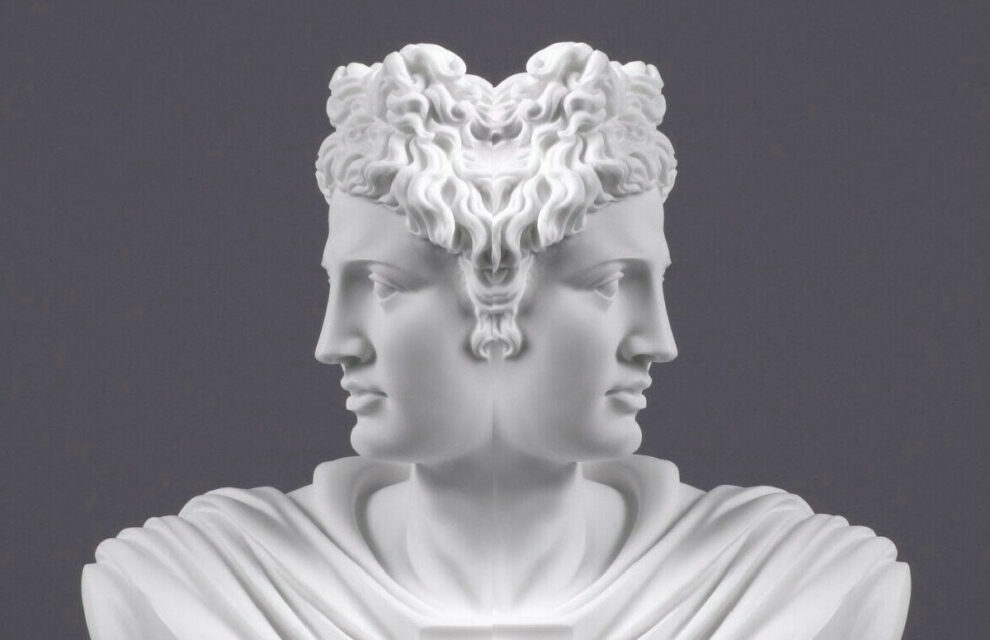

For example, how does a film-maker deal with the complexity of personality, or the changes a single character undergoes over the course of life? What if a character, like Amundsen, is sometimes empathetic, but other times callous? This could make him appear like the two-faced Roman god Janus, as shown in the feature image at the top of this blog: a person facing in two directions at the same time.

I notice in some Norwegian research about Amundsen that he is presented as either all good (a hero worth our admiration) or as all bad (a self-involved villain). There is such a tradition of Norwegians treating Amundsen as a hero that some Norwegian scholars eager to stake out their own research territory are only too happy to point out his character flaws.

Actually, this reminds me of a subject I have occasionally discussed in these blogs, and my podcasts: the perils of either/or thinking. Casting historical characters in binary, Manichean terms is reductionist. It is also a form of caricature.

In the rush to judgment, the “therefore syndrome” can induce a state of panic. A remedy to panic is patience, and it takes patience to make a feature documentary first of all, and then for the audience to sit through the film’s one hour forty-eight minutes of story-telling.

When making The Blinding Sea, I present the audience with new ways of seeing human interactions with Nature. This includes representing Inuit ways of seeing. And I did this by commissioning artworks by sculptor Damien Iquallaq, a descendant of Koleok, acquiring the rights to show graphic art by the late Victoria Mamnguqsualuk, showing some of Nanook of the North, playing with my camera, and occasionally inverting the colours of Nature scenes, for a more expressive effect.

And the expressive effect includes controlling the tone of my voice as narrator, creating soundscapes, performing and recording original music – all of which is far from the realm of straight facts in the logico-deductive mode.

Then again, to what extent can a film-maker use of visual metaphors in his or her story-telling? I show food dreams of starving explorers, paranoid delusions, and occasional fantasies, sometimes using animations for this purpose. I ask at one point whether Amundsen felt at home most of all at sea. This question has its place in a work about the oceans. But how is it to be conveyed in a film? I show storms at sea, mountains of water looming above the camera, the sense of vertigo as crew-members on sailing ships struggle to avoid being swept off the deck by rogue waves. I ask in one place whether the sea was Amundsen’s mistress, as a way of conveying that the sea was in authority or control over him, and commanded his respect. This is a metaphor sometimes used by Amundsen’s contemporary, the author Joseph Conrad.

Many people who love the outdoors invest the sea and even particular mountains, such as Mount Rainier in Washington state, with a metaphorical female persona. I suppose the people of Darjeeling, whom I mentioned in a recent blog, invest their extraordinary mountain Kanchenjunga with a male persona, since they often refer to it as “the Sleeping Buddha.” Metaphors are in the narrative mode, not the logico-deductive mode.

I remember the words of the 19th century German historian Leopold von Ranke, who said the goal of the historian is to show “Wie es eigentlich gewesen ist” or “How it essentially was.” If this is the standard to which a documentary film is held, particularly a historical one, then “How it essentially was” should include many dimensions of experience, including the inner world of emotional experience.

I have noticed so far, judging from recent reactions to the film in France, that audiences identify with Amundsen. Why? He was, in his own way, simplifying his life down to the bare essentials, emptying himself of distractions, and thrusting himself into harsh environments, even when that meant risking sudden death. I admit I have occasionally done this myself, making The Blinding Sea and producing radio documentary series for CBC Radio and Radio-Canada in the Guianese Highlands, Patagonia and the Sahara. One of the payoffs I got from this film has been … breathing the extraordinarily pure air of Nunavut, the Yukon and the Southern Ocean!