Continuing on the differences between academic research and film-making …

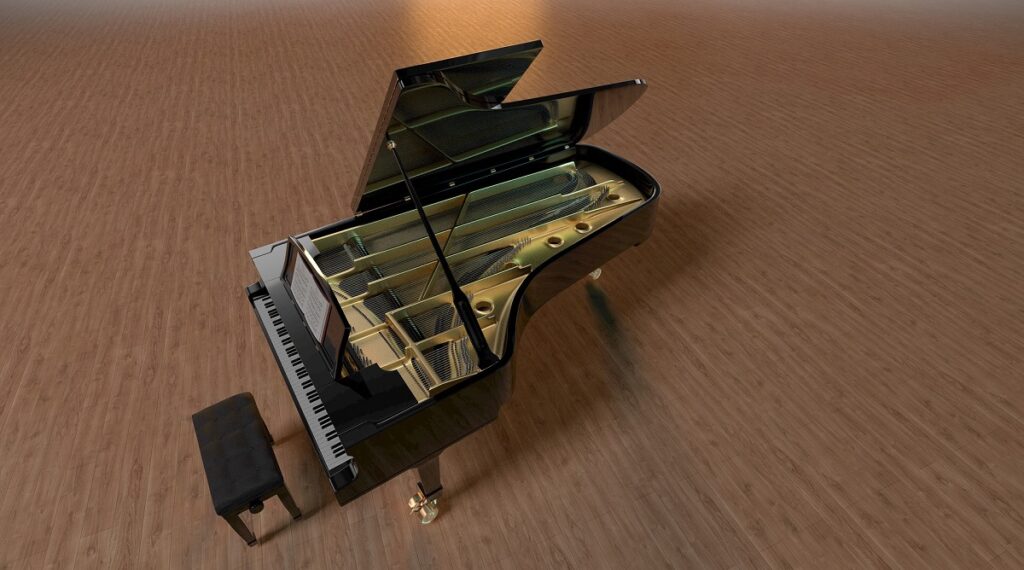

What is the role of music in a film? I put the question to Marie Frenette, who sings the haunting siren call in The Blinding Sea. We also perform several duets, with me at the piano. And she says: “dans des films, la musique est primordiale: elle est comme un des personnages” … in other words, “in films, music is essential: it is like one of the characters.”

I like the idea of music being a character of its own, having a distinct personality. And if I take the metaphor further, film music goes freely from scene to scene, reaching beyond words and communicating emotions directly to the audience. In fact, music provides emotional cues – signals to the audience that new experiences are starting, that previous experiences have not been forgotten, that the audience is here and now exploring the dramatic dimensions of characters and scenes together.

The conductor Leopold Stokowski once said: “A painter paints pictures on canvas. But musicians paint their pictures on silence.” Music sets the tone of a film; it brings melody and colour and structure.

When making this film, I worked with 16 other musicians: we composed and recorded 103 original pieces of music altogether, and also recorded four existing traditional pieces of music, for a total of 107.

Here are the musicians:

Piano and other keyboard music composed and performed by George Tombs

Vocal music composed and performed by Marie Frenette

Inuit throat singers: Janet Aglukkaq and Robin Ikkutisluk

Trumpet: David Carbonneau

Saxophone and clarinet: Cameron Wallis

Irish whistle: Brad Hurley

Violin: Catherine Hallmich and Laura Risk

Guitars: Pascal Desmeules and Marc Harvey

Percussion: Gilles Hébert

Choral ensemble 6-DS (from Quebec City)

It is interesting for the story, and also very important, that Roald Amundsen maintained lasting and respectful friendships, over several years, with Inuit women such as Koleok.

On the soundtrack, splendid throat-singing by Janet Aglukkaq and Robin Ikkutisluk establishes that the Inuit vision of the world and Nature is a different paradigm from what Amundsen was used to.

And since this film has so much to do with Nature, we include the song of trumpeter swans, like blowing jazz on brass.

Also, the crackling of aurora borealis, graciously provided to the production by California sound engineer Steve McGreevy; beluga whale recordings from the Groupe de recherche et d’éducation sur les mammifères marins (GREMM), in Tadoussac, Quebec; and humpback whale recordings from Catherine Berchok, at the Mingan Island Cetacean Study and Pennsylvania State University. We use some of these Nature sounds as the starting-point for jazz improvisations taking viewers up to the typical altitudes of aurora borealis and australis, 100 to 600 km above the Earth’s surface, as well as into the depths of the ocean, where humpbacks sometimes sing 150 to 210 metres below the ocean surface.

Occasionally I go for mock-epic music, for example when playing piano in a Klezmer-Gypsy theme along with violonist Catherine Hallmich, guitarists Marc Harvey and Pascal Desmeules … the kind of music that casts Amundsen as something of a wanderer when it came to love affairs. Of course, according to the director of a Norwegian museum I know, so were his Norwegian female partners, as their correspondence demonstrates.

Music provides emotional and/or geographical dimensions to new scenes, portraying characters in broad brushstrokes, plunging into their inner world of memory, joy and sorrow, hope and despair; music also gives an overall idea of the mood of characters, whether that mood be dreamy, fascinated, adventurous, hypervigilant, melancholy, Romantic, Gothic, nationalistic, delusional, panicky, prone to chaos, terrorized or awestruck.

So film music can be both an essential character and a way of painting emotions onto silence.