Inevitably, living by the St. Lawrence River as I do between Quebec City and Lévis, getting a whiff of brisk salty air each time the tide comes in from the Bas-du-Fleuve, continually watching ships pass by, I am reminded that so much happens at sea.

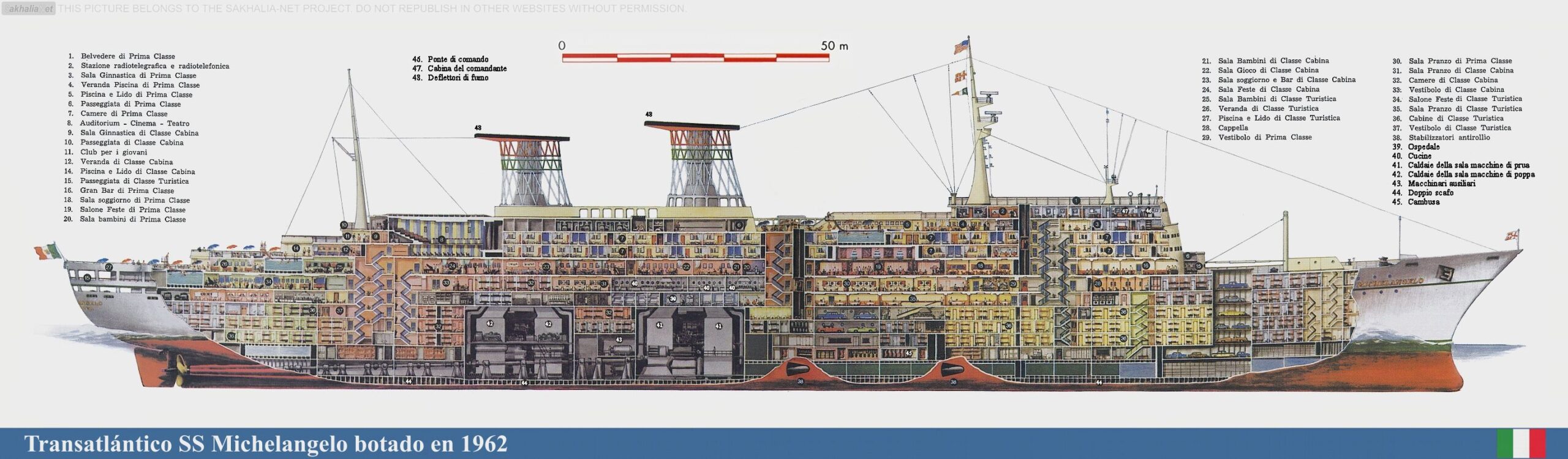

I think, for example, of the time my father invited our family to cross from New York to Naples, Cannes and Genoa on the Italian passenger liner Michelangelo (see the feature image at the top of this blog). This voyage came as a revelation for me. It changed my life.

During the crossing, the first officer Guido Bozzolo taught me how to plot a course on nautical charts, how to observe sea changes, how to keep an eye on Soviet submarines in the mid-Atlantic, how to watch for passing whales. He allowed me to stand at the wheel, steering this magnificent 45,900-tonne, 276-metre-long (906-feet) passenger liner for half an hour (under supervision), with over 1700 passengers on board! I was 12 years old at the time, so this came as an incredible honour, and I am sure nothing of the sort would be allowed nowadays.

While we were together on the bridge, Guido told me the most amazing stories about the sea, like the storm in April 1966, when the Michelangelo had to make her way through seas with 20-metre or 65-foot waves, and suddenly a monster wave descended upon the ship. Judging by the photo below, the wave must have been one-fifth the length of the ship – 55 metres or 180 feet in height.

Once we came through the Straits of Gibraltar, the captain granted me the rare privilege of remaining on the bridge during our rather tense passage through. By then, I had become the mascot of the Michelangelo, all the officers of the watch having grown used to me being around 10 hours a day.

Ships have always been part of my family upbringing and career. I have learned so much at sea: discovery and oblivion, love and hatred, disasters and rebirth, the business of maritime agencies, learning to manage with the unknown. The sea takes us back to a world of experience, where things take time to happen, and people have to help one another.

I remember my parents had spent their honeymoon on board the Canada Steamship Lines cruise ship St. Lawrence, from Montreal to Quebec City and Tadoussac, and then up the Saguenay River from there. This cruise was nothing like catching a flight nowadays. The ship was a hotel, a home-away-from-home for days and nights on end, a place for sharing and laughter, games of bridge with other passengers, and the relentless, gentle rhythm of a steam-driven vessel on a building sea.

When I was four, my father invited us on a holiday, crossing the Atlantic from New York to Lisbon on the Italian passenger liner Saturnia. I may have been too young at the time really to appreciate the voyage. I wanted to learn, but was not yet ready to. The smartly-dressed officers all in white taught me that Italy was a country to admire.

Several years later, my father invited us on a Mediterranean holiday, crossing the Atlantic on a far larger ship, the Michelangelo. The voyage out was completely different from anything I had experienced on the Saturnia. By now, at the age of 12, I caught on to the fact a passenger liner was a work of art, a city on the sea, a world unto itself.

And so many things happened on board! People falling in and out of love, Italian-American parents taking their teenage children over to visit the old country, stewards romancing bright-eyed young women in their late teens, some seasick passengers literally turning green and disappearing into their cabins, my brothers and me trying to paddle back and forth in the open-air saltwater pool, using my silver spoon in First Class to turn my scoop of gelato into a little melting volcano, and best of all my spending hour after hour on the bridge, learning the ABCs of navigation.

Once we got to Genoa, I remember we went to a hilltop, and saw the Michelangelo moored next to her sister ship Raffaello. An unforgettable sight. The Raffaello and Michelangelo were later bought by the Shah of Iran. After the Iranian Revolution overthrew the Pahlavi dynasty in 1979, the Raffaello was sunk by an Iraqi missile off Bushehr in 1983, while the ayatollahs transformed the Michelangelo into a prison for opponents of the regime, then sold her for scrap in Pakistan in 1991. A sad ending for these two vessels, surely the most beautiful I have ever seen. A lot of passenger liners nowadays look like giant top-heavy apartment blocks. I wonder how they even stay afloat!

Since that time, I have sometimes done reporting on sea and lake voyages, for example on the former Papachristidis bulker Feux-Follets, renamed the Canadian Leader.

Although many people picture a life at sea as being apart from human company, I have always seen voyages as a time for making contact with other people, engaging conversations and story-telling, like in the fiction of Joseph Conrad. Besides which, ships are close to communities on the St. Lawrence River and Great Lakes.

I realize now, with hindsight, that my feature film The Blinding Sea is yet another chapter of something that started long ago: adventures at sea, the place where so much happens.