At the moment, I am working on an expedition biography of Roald Amundsen, and I am struck how challenging it is to portray a person in a literary work, and especially a person I have never met, who lived in another era.

I say this because I brought out an unauthorized biography of Conrad Black in 2007, under the title Robber Baron and Le baron Black. Based on my years of research, interactions/interviews with him and hundreds of his family members, friends, colleagues, competitors and critics, as well as my own first-person coverage of his criminal trial in Chicago, I portrayed Mr. Black as fairly as I could, while holding him at least partly responsible for the incredible destruction of value he had built up since the 1960s.

The book was very well reviewed and received around the world, with one exception: Conrad Black himself simply hated it! I can hardly find this surprising. I remember him telling me once that some biographies are puff pieces, whereas others are hatchet jobs. This comment made biography seem utterly instrumental, like a tool of propaganda rather than a portrait.

I found his biography of Maurice Duplessis deeply troubling, because it glorified one of the darkest right-wing figures in Quebec history; many of his allies, American neocons, found his biography of FDR incomprehensible since it praised the New Deal, which they abhor; his biography of Richard Nixon seemed like a story within a story, a strangely self-justifying embedded narrative, as if Mr. Black were really writing not about the disgraced former president (who died in 1994) but about his own hoped-for redemption once he had served prison time (the book came out in May 2007, and he was convicted in July that year); his biography of Donald Trump is the ultimate puff piece, and no doubt helped him obtain a presidential pardon.

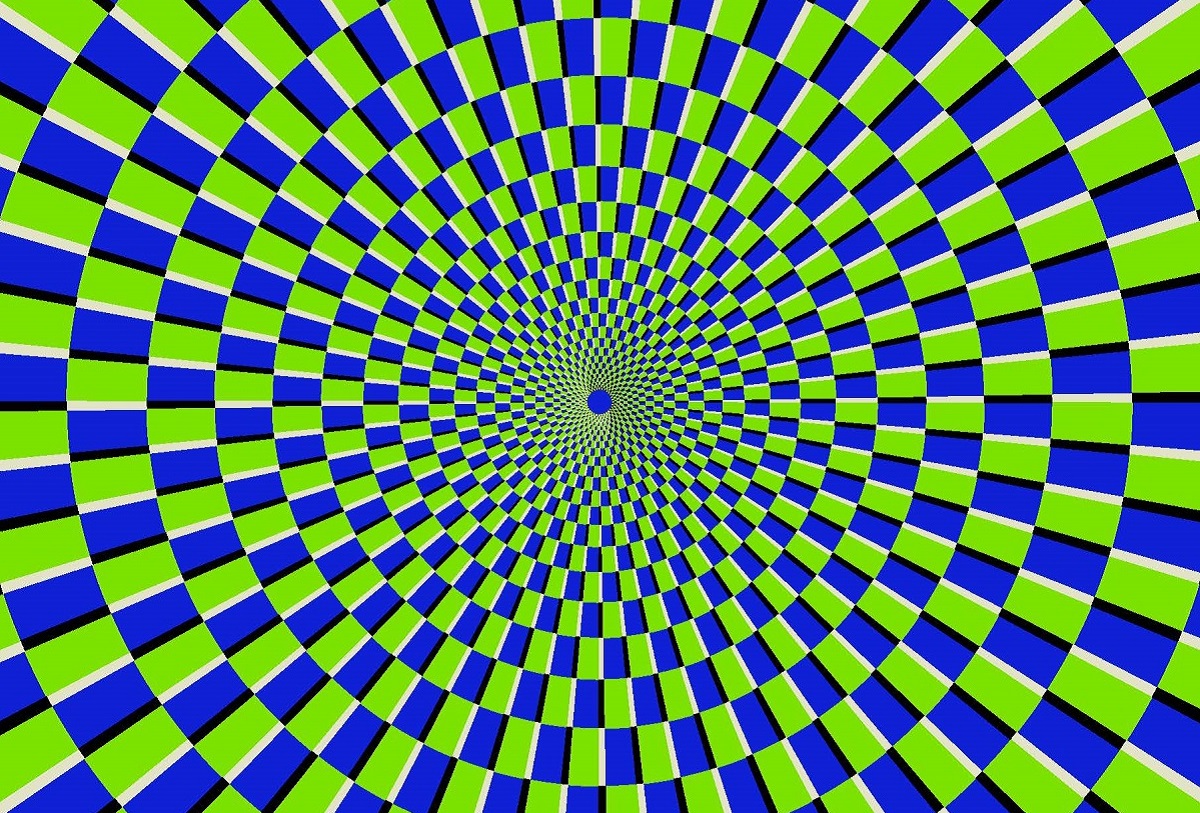

Actually, as the biographer of a convicted criminal, and a regular TV commentator, I completely zoned out at a certain point, turning down a lucrative job offer from a TV network where I would have been an investigative journalist reporting daily on financial crimes in the corporate world. By then, the subject of fraud filled me with dread, and even a sense of vertigo. I wanted to avoid getting sucked into the swirling, obsessive world of ruthless manipulation, sociopaths, charlatans and oversized egos in a delusional Hall of Mirrors.

I started my Amundsen project literally to get a breath of fresh air, making the feature documentary The Blinding Sea. And now I am working on the book. This has meant facing new challenges as a biographer!

So just who was my new subject?

Even in death, Amundsen is no stranger to controversy. He has variously been portrayed as the “conqueror” of the Northwest Passage, the South Pole and the North Pole; a latter-day Viking; a founding hero of modern Norwegian nationhood; a heartless narcissist; a world historical character; a master mariner and ski champion; a cunning rogue; an adventurer but not much of a scientist; a glory seeker; an intruder in what “by rights” ought to have been the British sphere of Antarctic exploration. But then polar exploration a century and more ago was a fiercely competitive business. And Amundsen was first and last a competitor. And a rebel.

As a biographer, I find there are habits of mind to shake off, because they contribute to what I would call narrative distortion. These habits of mind impact on interpretations of Amundsen himself, as well as his contemporaries and rivals, such as Adrien de Gerlache, Frederick Cook, Fridtjof Nansen, Robert Falcon Scott and Ernest Shackleton.

For starters, default thinking distorts our perceptions. It relies too heavily on the written or spoken record. A lot of the most important things in life are left unsaid, or can only be communicated with difficulty, since we lack the vocabulary to do that properly. The poverty of words. Making radio documentaries taught me the value of adding tone of voice, sound effects and music to story-telling; making a film taught me the value of driving the story with moving images.

Other people’s words can only take us so far. Amundsen was not a great writer; he lined up facts in a bare-bones fashion; he sometimes indulged in self-justifying rants, but he did not actually create myths about himself. Scott was a far more evocative writer, but in casting himself as a gentlemanly and ultimately tragic English hero against the harrowing and sublime backdrop of Antarctica, he created the most powerful mythology about himself. That is his legacy.

For a biographer to “debunk” mythology is no better, because the act of debunking simply replaces myth-making with myth-breaking.

Then again, there is the question what we do with our own words. It is always tempting to veer between hype and doom, between exaltation and fear, to heighten and exaggerate the contrast between personalities, portraying towering egos with broad brush strokes – egos locked in combat (e.g. Amundsen vs. Scott). I suspect this binary approach goes back to the scholastic legacy of dialectical reasoning, which consists in making inferences and either/or judgments, and in resolving contradictions. Unless it goes back to the heroes and dragons of medieval mythology. In which case, some biography is a form of fantasy writing.

Narrative distortion relies on appeals to authority, on an unthinking respect for people in power, for acknowledged authorities, as if they knew better and had set precedents or paths to follow. Narrative distortion also appeals to tradition, based on the conviction that people and situations were unalloyed, closer to the origins in times past, when ideas, values and faith were untainted by modernity. I can mention here the delusion of codes, which are based on decontextualized abstract principles, on placing the accent on what we do rather than how we do it. In addition, I can mention the writer’s own desire for recognition; cultivating novelty for novelty’s sake; attention-grabbing words; the society of the spectacle; the will to power; the will to evade responsibility for one’s decisions and actions; as well as appeals to class consciousness and national prejudice.

In the case of polar biographies, I reject the armchair approach, because a writer simply cannot imagine, from the vantage-point of a tranquil library, scenes and personalities in extreme polar environments. Why? Exploration of any kind has to do with acquiring knowledge; learning requires that we painstakingly unlearn what we thought we knew; in the case of Amundsen, exploration involved opening up to a new (Inuit) knowledge paradigm, which took him a few years.

In the face of all the challenges of myth-making, myth-breaking, the poverty of words and narrative distortion, I favour intersubjectivity. In this new biography, I am seeking to reconstitute real lived experiences as far as possible, in order to understand the many dimensions of Amundsen’s personality, including his values, experience, threats and opportunities, dream states, the driving force of his emotions, the way he defined himself through words and actions, his thought processes, world view and changes over time.