Nature is the source of many of the stories we tell, for better or worse. I have long seen the sea with its incessant movement and unpredictable moods and textures as a mirror of the human soul; and glaciers as miraculous holdovers from former times, slowly retreating like poignant memories; and trees as sentinels rooted in the soil, standing as nonjudgmental witnesses of human events. As we look at phenomena in Nature, we begin telling ourselves stories.

Walking along a footpath with my wife and son in Carcassonne in southern France while on a film tour last year, I stopped to look at some umbrella pines near our hotel. I took the feature photo above wondering what it would feel like to be a blackbird flying up to the tree-top. I was drawn to the way the huge branches twisted this way and that in a slow, deliberative movement which must have started off years before with a modest sapling reaching upwards for sunlight.

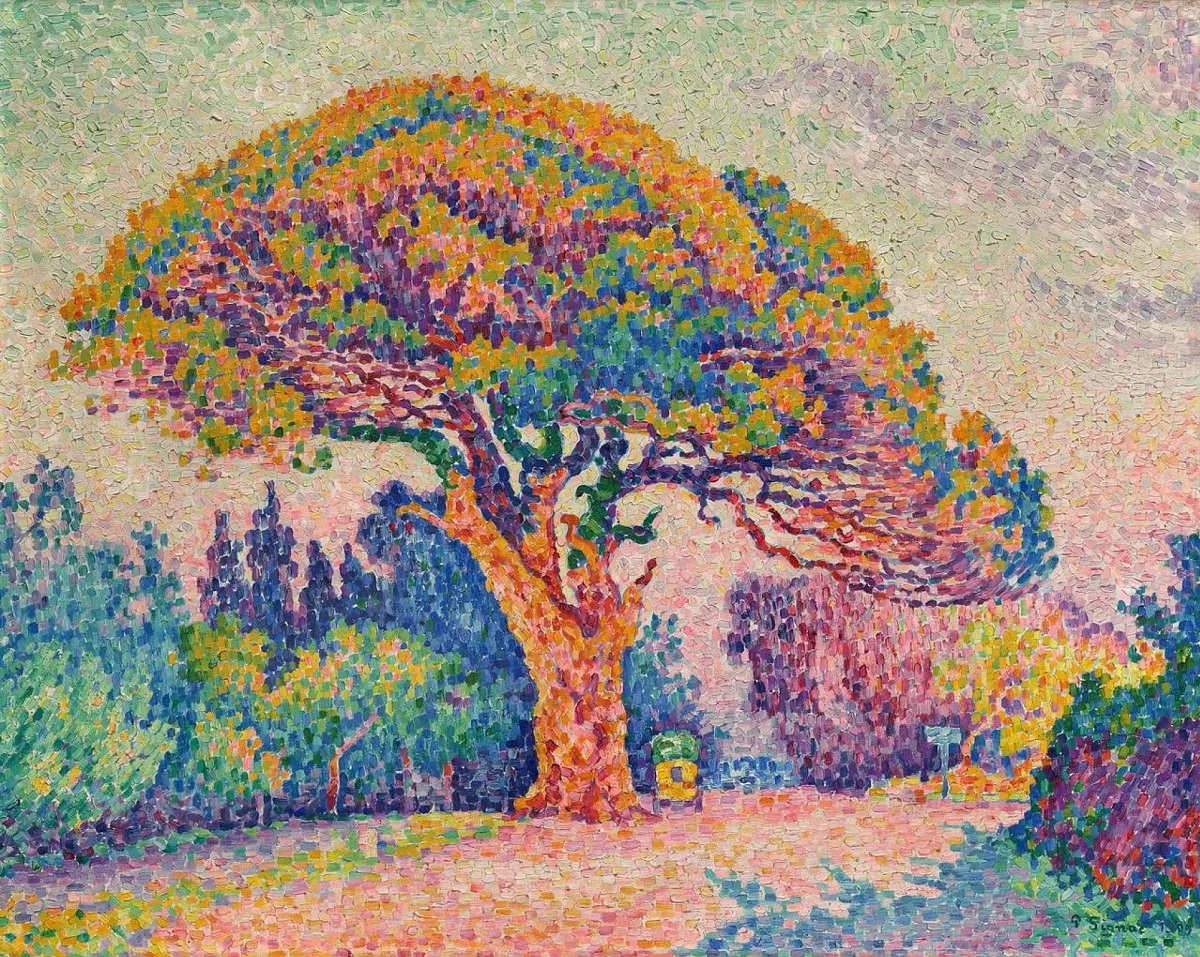

This suddenly reminded me of a visit to the Pushkin State Museum of Fine Arts, in Moscow, when I was 15. Of all the artworks there, the one that made the biggest impression on me was a neo-impressionist painting by Paul Signac from 1909, showing an umbrella pine in St. Tropez. Why? Because through his pointillist technique, forming luminous patterns of multi-coloured dots of paint, which we the viewers then blur or fuse in our minds, Signac reveals what it means to draw our sense perceptions together to form coherent images of Nature.

In his Theory of Colours, published in 1810, Goethe writes about the experience of the mind: “Looking at a thing gradually issues in contemplation, contemplation is thinking, thinking is establishing connections, and thus it is possible to say that every attentive glance which we cast on the world is an act of theorizing.” For Goethe, that glance is an act of interpreting, and for Signac so is the glance at an umbrella pine.

This partly answers the question I raised the other day. Does narrative come before, after or during what we experience? I have always wondered, in listening to Matthew 7:7 (“seek and you shall find”), whether we find what we are looking for and expect to see, and in so doing whether we create what we experience, at least some of the time.

But then, I never expected to see the painting by Signac in Moscow, and to be frank, it switched part of me on, it taught me a new way of seeing.

Then, while staying in Montpellier last year for a lecture-screening at the university there, I drew back the curtains of my hotel-room, before going out for supper, and was struck by the sight of umbrella pines in southern France, suddenly remembering Signac’s painting.

The dots of Signac’s pointillism strike me as very much like the pixels of my cinematography, and while making The Blinding Sea I had to keep a close eye on managing pixels, I had to study the scenes I was shooting and make calculations of light and shade, hue and saturation, brightness and contrast, down to the level of zones of pixels. It took me awhile, by trial and error, to learn that some crystal-clear images are inappropriate, because an utterly perfect, idealized image conveys the wrong kind of emotions, as if exquisite geometry were supposed to stand in for chaos. As for clarity, the dramatic context of the story requires or at least justifies a blurred image, for example when a character is suffering, or dying, or when I experienced disorientation on a storm-tossed sea, and had a hard time focusing my eyes, let alone the camera!

During the production, Nature lashed, slapped, pummelled, shook up, flung over, dazed, quick-froze, dehydrated and above all astonished me. This is a typical challenge facing film-makers in the polar regions. Nature scolded me when I was ill-prepared or deluded, and taunted me when I reached my limits. I learned to listen, otherwise the production … and my life … could well have ended then and there.

You can take two people and they will see pretty much the same thing; but if you include a third, troubled person, it may be a psychological or structural necessity for that person to form a highly altered image of what he or she sees, to have a distorted or even delusional view, even to the point of experiencing something the first two people simply could not recognize in a given situation. So in the case of that troubled person, perhaps the narrative kicks in before the experience, the narrative that person has already prepared guides along what he or she perceives, whereas for the other two people, they form images of their ongoing experience, and share that with each other, then form and share yet more images to develop a common understanding.

I have some experience of mountaineering. I sometimes find that volcanoes resemble the boiling-up, venting and explosion of human personality. I find volcanic eruptions fascinating … at a safe distance. But the next person may find eruptions simply terrifying, and something to be avoided at all costs, as if they disrupted the comforting regularity of everyday life. When we see with our emotions, we don’t always see the same thing.

I occasionally write on Evidentia of the dangers of analogical thinking; yet here I am drawing more analogies between Nature and human behaviour! The stories we tell are a mixed bag: sometimes we start off with the story, then apply it to an experience; other times, we story-tell in real time, as we move along; I can think of cases where the narrative only comes together after and even long after the fact. And then, stories change over time, don’t they, taking on a life of their own.