A decade ago, I had the pleasure of getting to know Marcel Trudel, the great historian of New France, then a retired professor from the University of Ottawa. I was translating his ground-breaking work on slavery in Canada for Véhicule Press. Trudel died on January 11, 2011, so he never saw my translation get into print. This work, Canada’s Forgotten Slaves: Two Hundred Years of Bondage, came out in 2012 and was a finalist for the Governor General’s Award for Translation the following year.

In this work, Trudel reveals the fates of over 4000 Aboriginal and Black slaves held in colonial Canada between 1632 and 1834. According to Trudel’s count, 2671 of these slaves were Amerindian, 12 were Inuit, and at least 1443 were Black.

You can get a copy, here: https://www.amazon.ca/Canadas-Forgotten-Slaves-Centuries-Bondage/dp/155065327X/

I remember writing in the preface about Trudel: “Even in his nineties, wearing eyeglasses as thick as fishbowls, surrounded by an impressive library of first editions, he was passionate about a historian’s duty to establish facts, ground them rigorously in statistical and documentary evidence, and bring them together in an appealing though balanced narrative. He was passionate above all, in a subversive, irrepressible way, about going against the grain, defying conventional wisdom in his native Quebec, making a contribution to the history of human rights.”

There is a movement nowadays to decolonize history. Researchers question the history of colonial Canada. Some protesters topple monuments to such famous figures as Sir John A. MacDonald, who played a key role in the creation of residential schools.

I wonder what would happen if we paid tribute to the slaves rather than the slave-owners. How would the names of places and institutions in Canada change, if the memory of slave-owners were no longer celebrated?

Here is a partial list of prominent slave-owners, many of whom are commemorated across the country, their names given to cities, counties, boulevards, streets, subway stations, a hydroelectric generating station, hotels, parks, parishes, sanctuaries, a university, schools, libraries etc.:

Louis de Buade de Frontenac, Governor General of New France 1672-1682 and 1689-1698 (slave-owner)

Charles Lemoyne, Baron de Longueuil, officer, Governor of Trois-Rivières and later of Montreal, acting administrator of New France, lived 1656-1729 (owner of ten slaves)

Philippe Rigaud de Vaudreuil, Governor General of New France 1703-1725 (owner of eleven slaves)

Marguerite d’Youville, founded the Grey Nuns of Montreal, lived 1701-1771, made a saint by Pope John Paul II in 1990 (owner of three slaves)

Charles de la Boische de Beauharnois, Governor of New France 1726-1746 (owner of twenty-seven slaves)

Pierre Gaultier de La Vérendrye, fur trader and explorer, lived 1714-1755 (owner of three slaves)

Marie Anne Catherine Fleury dite Deschambault, Baroness de Longueuil, lived 1740-1818 (slave-owner)

Paul-Joseph Lemoyne de Longueuil, Governor of Trois-Rivières 1757-1760 (owner of twenty-three slaves)

The Jesuits under the French régime (owners of forty-six slaves)

The Séminaire de Québec, a community of secular priests under the French régime (owners of thirty-one slaves)

The Montreal Gazette, newspaper (owners of at least three slaves)

John Askin, fur trader, merchant, office holder, and militia officer in Upper Canada, lived 1739-1815 (owner of twenty-three slaves)

Sir John Johnson, Loyalist leader during the American Revolution, British Loyalist/provincial military officer, a politician in Canada and wealthy landowner, lived 1741-1830 (brought fourteen Black slaves with him to Canada)

James McGill, merchant and member of the Legislative Assembly of Lower Canada, lived 1744-1813, left a legacy that was used to found McGill University in 1821 (owner of six slaves)

John Campbell, businessman, justice of the peace and seigneur in Lower Canada, lived 1787-1855 (owner of seventeen slaves)

This list does not include explorers and colonial authorities who committed kidnappings, hostage-takings and other forms of arbitrary captivity.

I have met people who deny the importance of slavery in colonial Canada, in seven different ways.

The heroic argument: Slaves were well-treated in New France, and were practically considered members of the families that owned them.

The lesser-of-evils argument: Religious orders and institutions that held slaves were protecting them from greater harms.

The blame-the-victim argument: Slaves passively accepted being in bondage, and could have become free if they had really wanted to.

The selective denial argument: The real problem was British slave-owners (after the Conquest), not French slave-owners. Trudel attacks head-on the angelist distortions of French-Canadian nationalist historiography. I remember a Quebec historian/former cabinet minister stringing this line as well. Actually, 85.5% of the slave-owners Trudel identifies between 1632 and 1834 were francophone, and 14.5% anglophone.

The not-America argument: OK, there were slaves in colonial Canada, but they were never in the same numbers as in the United States, nor were they subjected to such bad treatment.

The one-of-many-evils argument: Slaves were not treated worse than other people in colonial society, such as indentured labourers, young men kidnapped by press gangs, etc.

The social-conventions argument: Slave ownership was generally approved throughout society, so it was OK, up till the point the British Parliament outlawed slavery throughout the British Empire in 1833, at which point, suddenly, it was no longer OK.

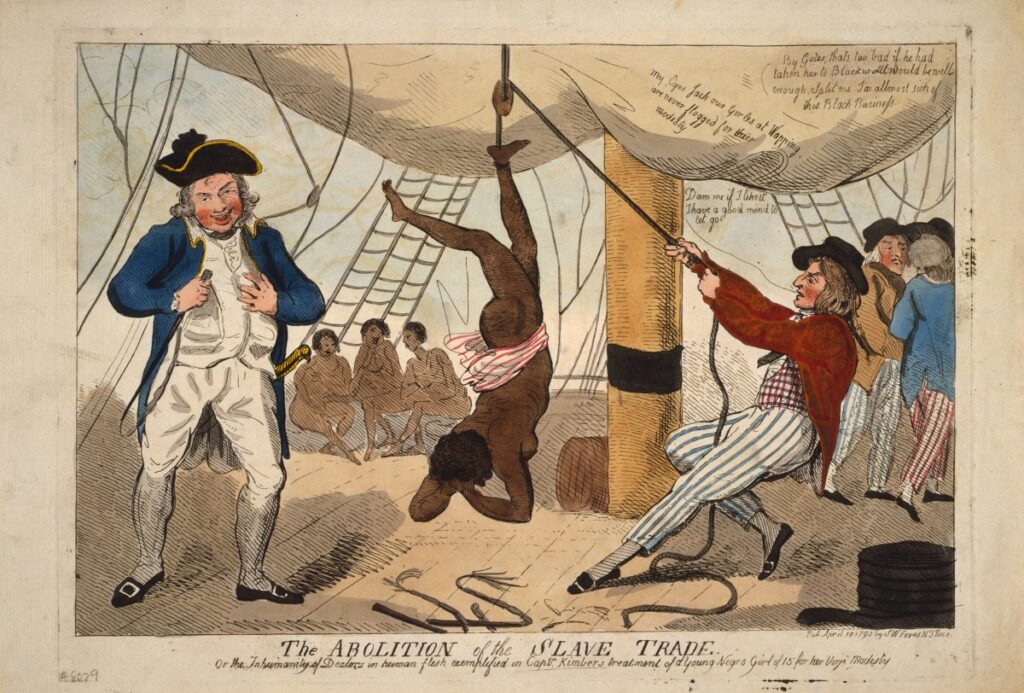

Overall, under both the French and British régimes in colonial Canada, slaves were bought, bartered and sold. They were seized as war booty and sought out by slave traders on the West African coast, in Madagascar, in the Caribbean or in the Great Lakes region/Mississippi basin. As slaves, they were forced to provide unpaid labour. They were denied legal rights under the law and sometimes exploited for reproductive purposes by slave-owners, who automatically owned the children they had with their slave concubines. They could be offered as gifts (bribes) to powerful people to curry favour, and faced the prospect of abuse, physical torture and execution if they tried to regain their freedom.

As I mention in the preface to my translation: “One of the most remarkable parts of [Trudel’s] work is in establishing that slaves did not passively wait to be freed by others; some slaves researched their condition, filed lawsuits, challenged their master’s ownership rights, sought to negotiate their release or simply ran away.”

And in one documented case, a free Black accepted a return to bondage in order to marry the female slave he loved. Trudel’s passage on p. 210 speaks volumes about the strength of character and commitment of the Black slave Louis-Antoine, originally from Cap Français, then the capital of Saint-Domingue (modern-day Haiti): “The Montreal merchant Dominique Gaudet faced a dilemma in March 1761 when his fifteen-year-old black slave Marie-Catherine Baraca fell in love with the twenty-year-old black Louis-Antoine. The latter had been free from childhood, but the merchant Gaudet had no intention of losing his slave Marie-Catherine. The person who found a way out of this situation, on March 26, 1761, was none other than Louis-Antoine himself, who accepted before a notary to return to slavery, selling himself to Gaudet.”

Frank Mackay has translated the actual contract as follows: “Whereas the said Gaudet is willing to grant him in marriage Catherine Baraca, Louis-Antoine has by these presents sold himself to the said Gaudet, the said Louis-Antoine and Catherine Baraca to remain in the service and under the power, mastery and authority of the said Gaudet, who may as he chooses dispose of and sell them, as well as the children to be born of their marriage. By these presents, the said Gaudet at his death, intends that the said Louis-Antoine, Catherine Baraca, and the children born of their marriage shall go free, his heirs to have no claim whatsoever upon them.”

Gaudet died in 1769, after which Louis-Antoine and Marie-Catherine Baraca were freed.

Slaves in colonial Canada were ultimately emancipated starting in 1834, but then were largely forgotten. To this day, the masters are remembered far more often than the slaves. Will this ever change?