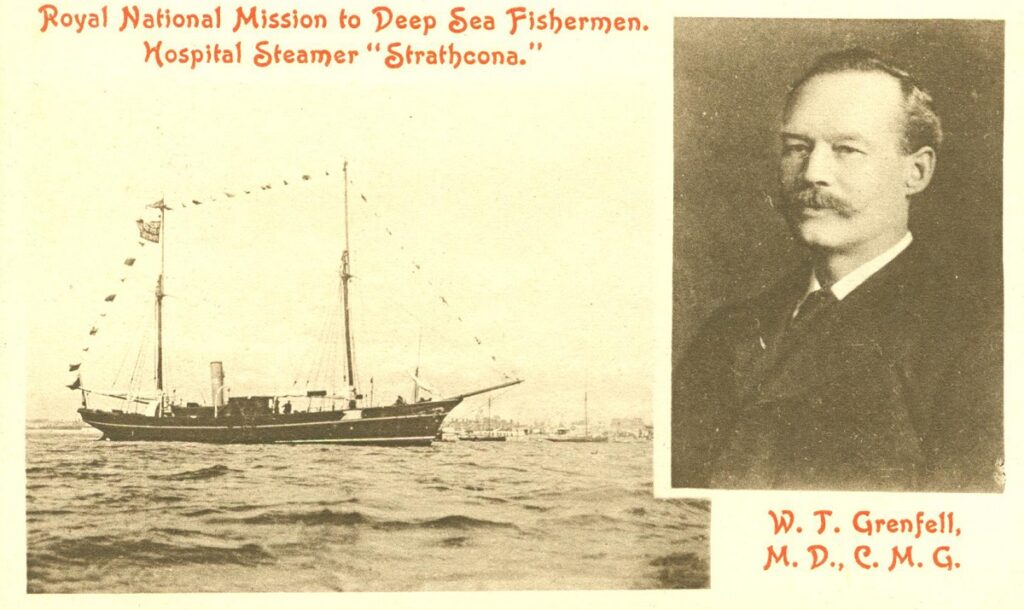

Sir Wilfred Grenfell (1865-1940) is often celebrated for having introduced health care to northern Newfoundland and Labrador. He showed enterprise and dedication, in adapting to a harsh sub-Arctic environment, spending four decades along the coast.

In setting up the International Grenfell Association, with its network of hospitals, nursing stations, residential schools in Cartwright and Northwest River, and cooperatives, he serves as a reminder of the age of heroic medicine, of “chivalrous” autocratic doctors, of an age that came before the creation of public health departments, organized by government bureaucracies.

Anthropologist Andrea Procter has just brought out a remarkable book, A Long Journey: Residential Schools in Labrador and Newfoundland, which recounts the story of residential schools from the point of view of the survivors.

You can find her book here: https://www.amazon.ca/Long-Journey-Residential-Labrador-Newfoundland/dp/1894725646/

But there is more to the story than that, as a careful reading of Grenfell’s own works indicates.

As I describe in a recent WildTrekker podcast, https://www.evidentia.net/wildtrekker/grenfell-of-labrador/, Grenfell went through a harrowing transition during the course of his life. In his younger years (1890s), his disciplinarian vision was well-suited to the context of Empire, a context demanding individual enterprise and initiative. He came out of the public-school tradition in England, which combined Victorian Muscular Christianity, harsh physical punishment, and the ideal of the gentleman in a vertical hierarchy of superior and inferior classes of society. In his latter years (1930s), he combined this disciplinarian vision with right-wing ideologies from Europe, according to which a dictator or a small commission of experts could wield considerable power over the masses.

In bringing health care to the Labrador coast, for example, Grenfell was giving large families of Liveyeres and Aboriginals the means to survive and build an independent life of their own.

Grenfell acted as health-care provider, educator and public benefactor, tending to the needs of Labradorians. As an evangelical Anglican, he sought to emancipate the people of northern Newfoundland and Labrador from the influence of the Catholic Church and the Moravian Brethren; he sought to free them from the exploitation of trading monopolies; he sought to offer them a more stable life, through social development, schooling and health care.

He was extremely well-known in his day, and capitalized on this fame to raise funds to support his work. He crafted a compelling self-image, giving the British, Canadian and American public something they badly needed, at the turn of the century and then through the years of the First World War and the Great Depression: a role model they could believe in. He was dedicated, resourceful, knowledgeable. The health-care institutions he set up improved and saved countless lives. How could anyone object to that?

Most of Grenfell’s books are at least partly autobiographical. Writing and rewriting his autobiography is a form of self-mythologizing, as he builds up a flattering, larger-than-life image of himself, and contrasts his own heroic enterprise with ignorance, degradation, avoidable illness, exploitation and domination. These passages are especially poignant when he describes the suffering of children. Several of the books contain photographs showing sick and handicapped children.

An extraordinary self-promoter, spinning one best-selling book after another, Grenfell romances the story: he casts himself, whether directly or indirectly, as a pioneering self-effacing medical missionary; he comes across in his own writings as a charismatic leader totally committed to emancipating a forgotten people, a humble saviour in the sub-Arctic wilderness, a servant of men and also of God.

By the early 1930s, Grenfell’s views of the world hardened. He became an avowed fascist and Mussolini supporter, at a time when there was no mystery about the tyrannical nature of Mussolini’s rule, whether in Italy itself, or in its extremely violent conquest of Libya throughout the 1920s. Mussolini’s armed forces used chemical warfare against indigenous people in Libya, summarily executed combatants who had already surrendered, slaughtered civilians and committed half the population of Cyrenaica (one of Libya’s three provinces) to fifteen concentration camps, where there were countless deaths due to the lack of water, food and medicine. Fascist Italy committed war crimes in its war of conquest. There was considerable cruelty on the Libyan side as well.

In the 1932 work, Forty Years for Labrador, Grenfell refers approvingly to Mussolini (p. 188): “On an Italian wall recently I saw posted one of Mussolini’s epigrams. It read, ‘We must not be proud of our country for its history only, but because of what we are making it today.’”

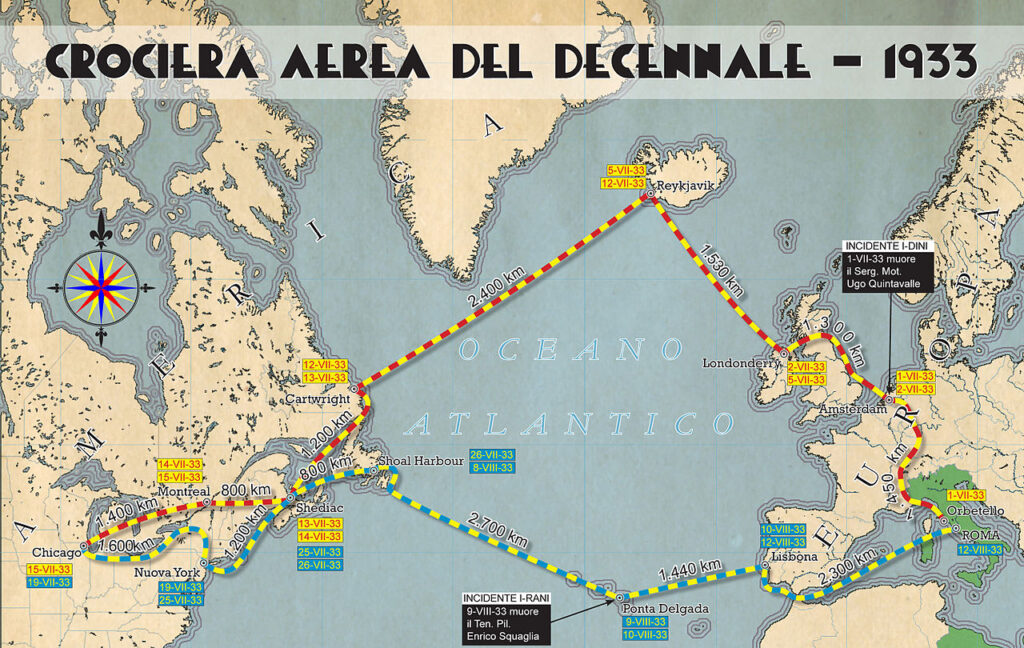

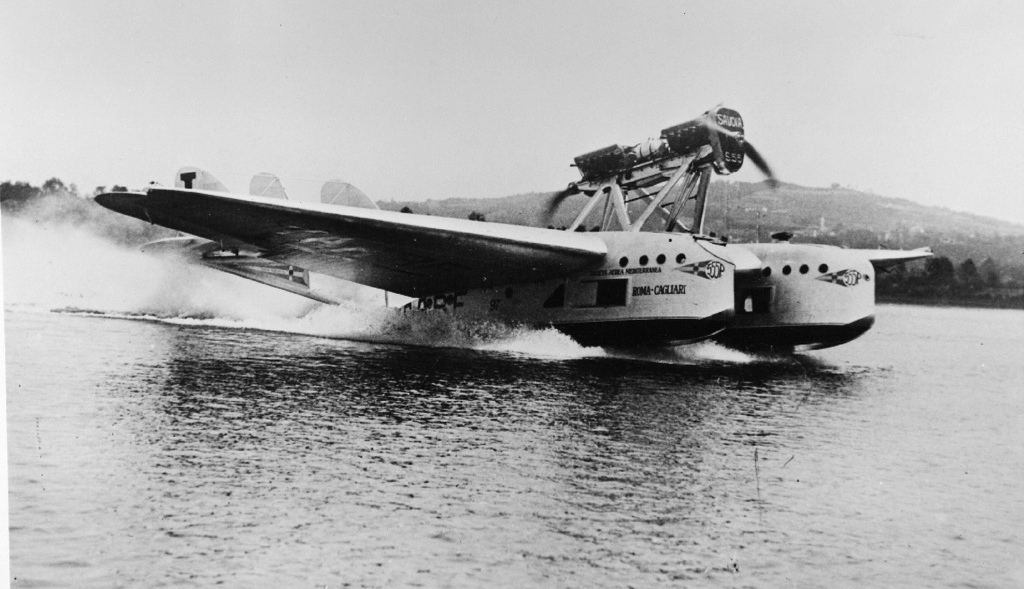

A quote like this, in a best-selling work by a famous British medical missionary, would not have gone unnoticed in fascist Italy. Grenfell’s support had a lot of propaganda value for the Italians. It is likely this flattering reference to Mussolini is the reason General Italo Balbo’s flotilla of twenty-four Savoia-Marchetti S.55 flying boats touched down at Cartwright, Labrador in July 1933, during a long flight marking Mussolini’s first decade in power. The flying boats were on their way from Italy to the Chicago World’s Fair. They made other stops in Amsterdam, Londonderry and Reykjavik before reaching Labrador. They then landed briefly at Shediac and Montreal, before heading on to Chicago. There was no particular reason to touch down in Labrador. Other sheltered bays were available in Newfoundland. General Balbo must have known Grenfell had gone on the record as an admirer of Mussolini.

In a subsequent book, The Romance of Labrador (1934), Grenfell quotes Mussolini’s epigram once again, on the very first page, in the very first paragraph (p. xiii): “This book is an attempt to record the scientific and historic facts about Labrador, as far as they are known. It is the audi alteram partem of a medical man, who has spent much of the past forty years on those coasts, and who admires greatly Mussolini’s dictum, ‘We must not be proud of our country for its history, but for what we are making of it to-day.’” The Latin expression audi alteram partem is used in court when someone seeks to get a fair hearing, by responding to the evidence presented against him. In using this expression, Grenfell suggests he is on the defensive, as if he were being unfairly treated by his opponents. Perhaps he is casting himself as both hero and victim!

Grenfell then goes on, in another passage (p. 315), to show how he applies fascism in Labrador: “A combined boarding-school and orphanage in Sandwich Bay, with fifty-five resident children was suddenly wiped out by fire … but a better building has replaced it, on a large grant of land at Cartwright; now made famous by General Balbo, who was welcomed by Black Shirts from our Lockwood School, bearing the fasces of lictors.”

In other words, on July 12-13, 1933, Grenfell actually had these children, some of them native Labradorians, dress up in fascist uniforms (black shirts), and form a procession as they saluted over a hundred triumphant Italian aviators. The children pushed along, brandishing axe heads projecting from bundles of birch or spruce rods. What an incredible scene!

What values was Grenfell trying to inculcate, in having Liveyere and Aboriginal children dress up in fascist black shirts? What was he trying to achieve in getting them to celebrate the arrival of General Balbo’s twenty-four flying boats on the Labrador coast, in having them carry symbolic fasces, as if they were lictors in a solemn fascist procession in Italy? He was a highly educated man, who had access to the world press and knew about world events. He cannot be written off simply as a naive or bitter person, whose views had by now hardened.

Grenfell’s words in this passage are clear. The school in Cartwright was “now made famous by General Balbo.” By creating a news event in July 1933, by rhetorically associating the International Grenfell Association with the military might of Italian fascism, Grenfell was raising the profile of his own work in Labrador. The visibility offered by this event would illustrate his sympathy for autocratic rule, and would help fund-raising. That he should describe this event in a book called The Romance of Labrador, a book presenting history as a series of romances full of vivid pageantry, is very disturbing from today’s perspective. The event gives the impression he saw himself as a colonial dictator, or wished to become one. Certainly his own support in the 1930s for the suspension of representative government in Newfoundland, and rumours he might himself become the autocratic governor of the colony, are along these lines.

Meanwhile, having Labrador children celebrate the arrival of a fascist general and his flotilla of flying boats in July 1933 is part of the legacy of the residential schools, and deserves more attention.

In recent years, the Truth and Reconciliation Commission has examined the fate of Aboriginal students in residential schools in Canada. This led to a legal settlement between the Canadian government and the survivors. Newfoundland and Labrador joined the Canadian Confederation in 1949, and the treatment of Aboriginal students after 1949 was the subject of a second legal settlement.

There is far greater awareness nowadays of the damaging effects that residential schools had on children. The Lockwood School in Cartwright had a few Aboriginal students at the time, but seems mainly to have been made up of Liveyeres. According to Andrea Procter, the residential schools operated by Grenfell enforced a harsh regime of physical and psychological discipline (caning, humiliation, abuse), canned food in place of fresh food, and the vertical prejudices and gender roles of the British middle class, for example by assigning female students to serve as maids for the teaching staff. True, many of these conditions also prevailed at the time in boarding schools close to urban centres. The difference is that residential schools were used to take Aboriginals away from their families, often punishing them for speaking their native languages, as part of a policy of cultural assimilation.

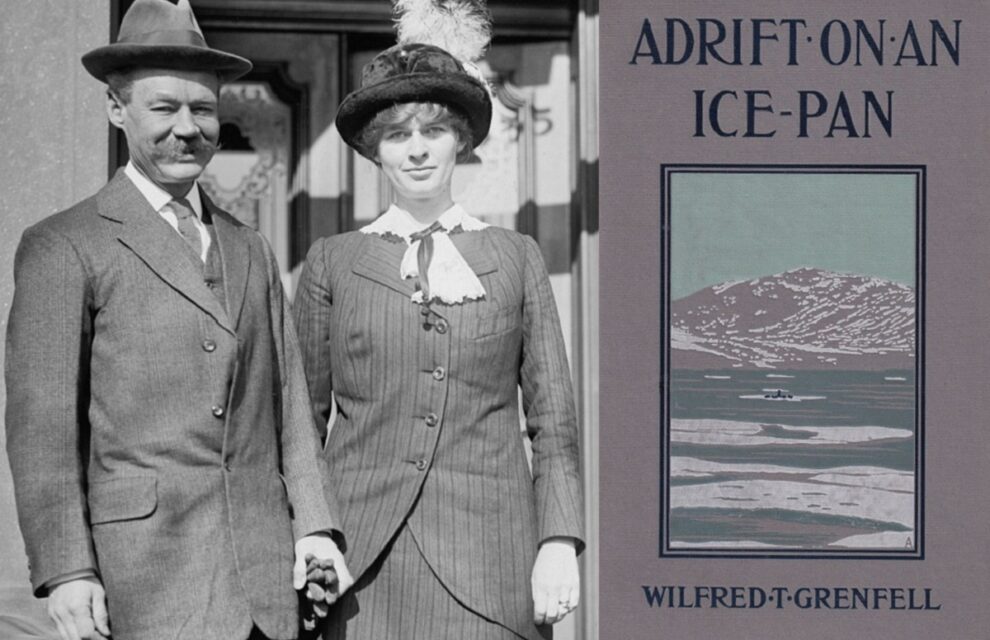

The feature image at the top of this blog combines two photographs. On the left, Grenfell stands next to his wife Anne Elizabeth Caldwell MacClanahan. They met on a transatlantic passenger liner in 1909. Photo courtesy of the Library of Congress. On the right, he managed to survive being marooned on an ice-pan off the coast by eating three of his huskies, as recounted in his best-selling book Adrift on an Ice-Pan, also from 1909.