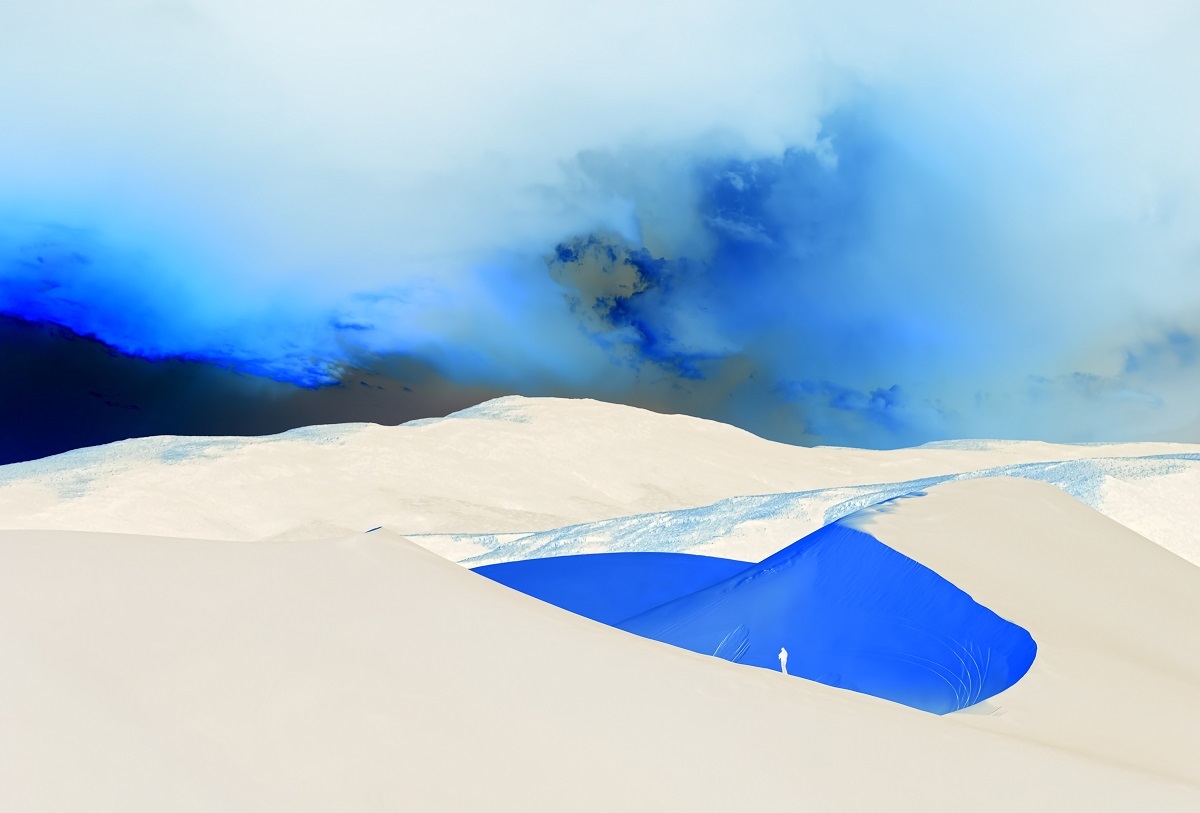

Dreams are often more gratifying than waking thoughts. Dreams take us wandering through imagined mindscapes where we break free from inhibitions, projecting ourselves into uncharted places. We soar on wings of desire, compensate for our frustrations of the previous day, effortlessly make everything possible – changing the colour of life, squaring the circle, reversing injustices, suspending death long enough to converse once again with departed loved ones. In dreams we experience the potential as something real. There is no question of experiencing the actual.

Our dream perceptions have a shimmering, fluid, tingling, shifting, evanescent quality, like a personal mythology full of meaning that is only threatened when the harsh glare of morning wakes us up. In the alternate world of dreams, there is nothing necessary about reality.

My magical-realist novel Mind the Gap occasionally dips into the grey zone between the fantastic, the dreamed, the grotesque and what we take for reality.

The gap between dreams and waking thoughts can be unsettling, as the Bulgarian literary critic Tzvetan Todorov reminds us in Introduction à la littérature fantastique, which examines alternate realities developed by Jean Potocki, Gérard de Nerval, E.T.A. Hoffmann, Edgar Allan Poe and others: “La littérature fantastique implique … non seulement l’existence d’un événement étrange, qui provoque une hésitation chez le lecteur et le héros; mais aussi une manière de lire…. Nous sommes maintenant en état de préciser et de compléter notre définition du fantastique. Celui-ci exige que trois conditions soient remplies. D’abord, il faut que le texte oblige le lecteur à considérer le monde des personnages comme un monde de personnes vivantes et à hésiter entre une explication naturelle et une explication surnaturelle des événements évoqués. Ensuite, cette hésitation peut être ressentie également par un personnage; ainsi le rôle de lecteur est pour ainsi dire confié à des personnages et dans le même temps l’hésitation représentée, elle devient un des thèmes de l’oeuvre; dans le cas dune lecture naïve, le lecteur réel s’identifie avec le personnage. Enfin il importe que le lecteur adopte une certaine attitude à l’egard du texte: il refusera aussi bien l’interprétation allégorique que l’interprétation poétique.” (pp. 37-8)

My translation: “Fantastic literature implies not only the existence of a strange event causing both reader and protagonist to hesitate a moment; it is also a way of reading the text…. We now reach our definition of the fantastic. Three conditions have to be met. First, the text has to make the reader see the world of fictional characters as a world of real living people, but the reader hesitates between a natural explanation and a supernatural explanation of the events described. This hesitation must in turn be experienced by a fictional character, so the role of the reader is to be wrapped up in the world of the characters and to see hesitation as one of the defining themes of the work; the unsophisticated reader may even identify with the main character. Finally, the reader needs to interpret the text neither as allegory nor as poetry.”

Is there always such a hard-and-fast either/or difference between dreams and waking thoughts? Why contrast one with the other? What if projecting a dream and pursuing a line of thought sometimes go hand-in-hand? What if stretching one’s mind becomes a way of compensating, of projecting, like an inventor determined to turn his or her dream into reality? In the case of invention, the dream seems silver-etched on the mind, before it is realized in broad daylight.

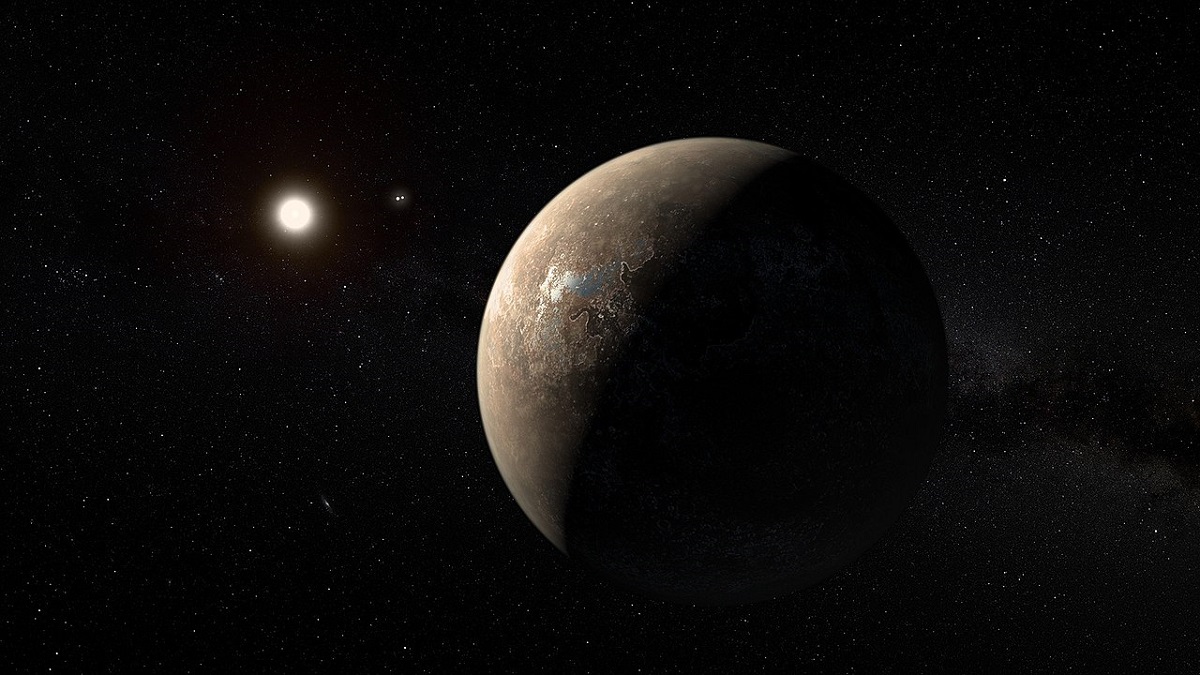

The discovery of exoplanets is a good example of observations going hand-in-hand with speculation about alternate realities. And I don’t mean to belittle the work of astronomers. Far from it.