The history of polar exploration a hundred and more years ago provides important lessons about the way people develop hierarchies of knowledge, and decide which knowledge is worth learning, and which is not worth their time.

What is a knowledge hierarchy? Drawing from the Oxford English Dictionary, I would say it is “a system of arrangement or classification of knowledge according to relative importance or inclusiveness.”

A hierarchy is a way of ranking things; the earliest sense of this word, the OED tells us, is “a system of orders of angels and heavenly beings.” That necessarily means angels and heavenly beings are above mortal beings here below on earth. So, a knowledge hierarchy is vertical, like a pyramid.

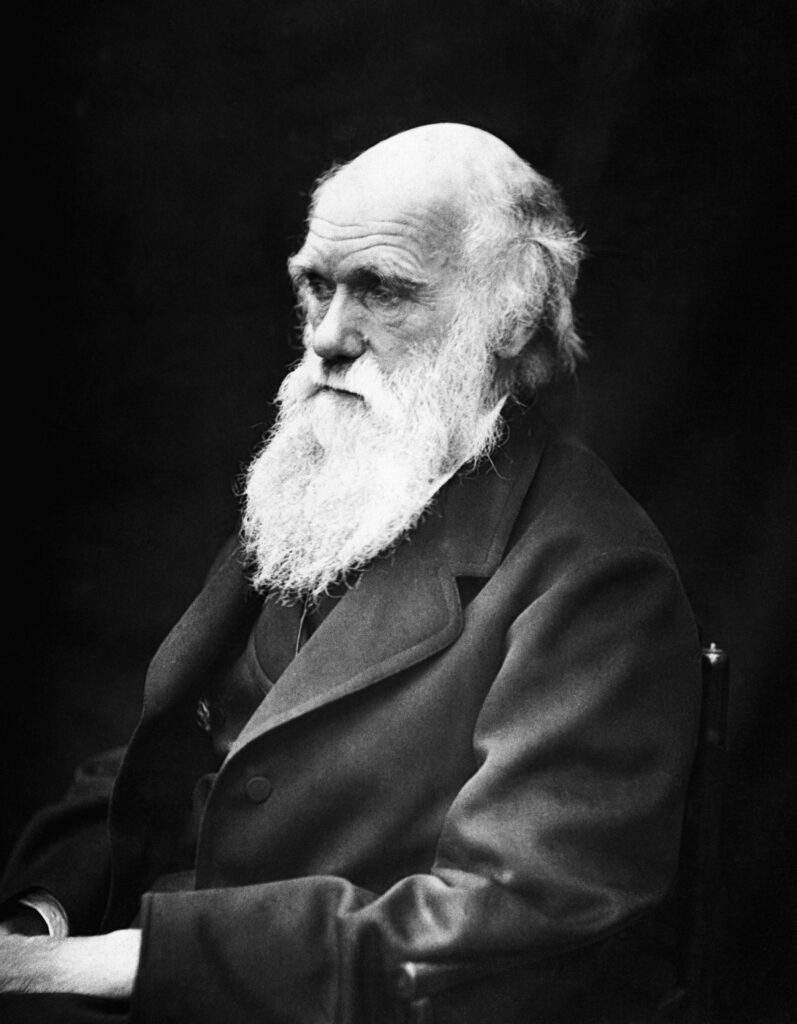

In the late 19th century, when the minds of Roald Amundsen and Robert Falcon Scott were being formed, science was widely seen as a secular religion, the very culmination of civilization’s pursuit of knowledge. For many people of the time, science was the surest sign that humanity was making progress. Science was a creation of superior minds, like the mind of evolutionist Charles Darwin. Science was at the very top of the knowledge hierarchy. According to Darwin, the white races were more advanced than other races, so it was only natural that the knowledge of other races should be ranked far lower on the hierarchy. He also believed men to be intellectually superior to women which is, to say the least, not very realistic!

Imperialists and racists considered that whatever knowledge Aboriginals developed was unsettling, hard to explain, anecdotal, possibly even instinctive. Aboriginals were “uneducated” in the Western sense of the word, they knew little about science, and they didn’t write up their findings for publication. So how could Aboriginals develop tacit, experiential knowledge that was based on more solid evidence and was less speculative than the science of the time?

A flagrant example of this knowledge hierarchy is provided in 1873 by Charles Darwin, in quoting an observation by Ferdinand von Wrangell, a Russian polar explorer of Baltic German origin. Actually, von Wrangell showed respect for the empirical knowledge of Kazakh and Yakut (or Sakha) sledge-drivers in northeastern Siberia, whereas Darwin, in later quoting von Wrangell, transformed this Aboriginal skill, observation and experience into unthinking instinct.

In Narrative of an Expedition to the Polar Sea, written in 1820-1823, but only translated into English in 1840, von Wrangell writes: “Before proceeding further with my narrative, I must mention the remarkable skill with which our sledge-drivers [my note: it is clear from the context that von Wrangell is speaking mainly of Yakut, or as we would says nowadays Sakha, sledge-drivers] preserved the direction of their course, either when winding amongst large hummocks, or on the open unvaried field of snow, where there were no objects to direct the eye. They appeared to be guided by a kind of unerring instinct. This was especially the case with my Cossack driver, Sotnik Tatarinow, who had had great practice for many years. In the midst of the intricate labyrinths of ice, turning sometimes to the right and sometimes to the left, now winding round a large hummock, now crossing over a smaller one, among all the incessant changes of direction, he seemed to have a plan of them all in his memory, and to make them compensate each other, so that we never lost our main direction, and whilst I was watching the different turns, compass in hand, trying to resume the true route, he had always a perfect knowledge of it empirically. His estimation of the distances we had passed over reduced to a straight line, generally agreed with my determinations deduced from observed latitudes and the day’s course. It was less difficult to preserve the true direction on a plain surface.”

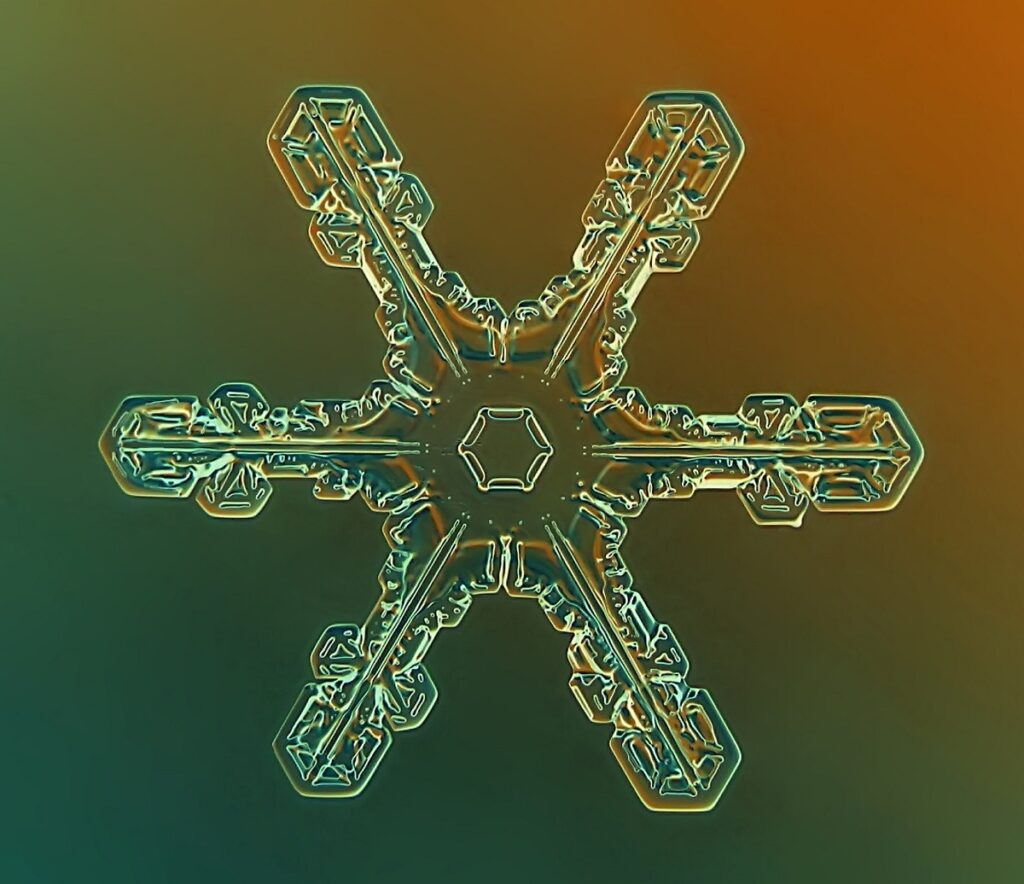

Von Wrangell continues: “To enable us to follow as straight a line as possible, we tried to fix our eyes on some remarkable piece of ice at a distance; if there was none such, we were guided by the wavelike stripes of snow (sastrugi) which are formed, either on the plains on land or on the level ice of the sea, by any wind of long continuance. These ridges always indicate the quarter from which the prevailing winds blow. The inhabitants of the Tundras often travel to a settlement several hundred wersts off, with no other guide through these unvaried wastes than the sastrugi. They know by experience at what angle they must cross the greater and the lesser waves of snow in order to arrive at their destination, and they never fail. It often happens that the permanent sastruga has been obliterated by another produced by temporary winds, but the traveller is not deceived thereby, his practiced eye detects the change, he carefully removes the recently drifted snow, and corrects his course by the lower sastruga and by the angle formed by the two. We availed ourselves of them on the level ice of the sea, for the compass cannot well be used while driving; it is necessary to halt in order to consult it, and this loses time. Where there were no sastrugi, we had recourse to the sun or stars when the weather was clear, but we always consulted the compass at least once in every hour.”

So this navigational ability was based on keen observations of snow formations (sastrugi) running over the polar ice-pack, whose hardness was an indication of their age; they were in turn an indication of the direction of the prevailing wind, which in turn served as a kind of weather compass for sledge-drivers. I am sure a multitude of other observations also came into play, such as the direction of sunlight and the movement of stars over the polar sea. On land, sledge-drivers would also have taken into consideration the lie of the land (the Kolyma River and many other Siberian rivers flow northwards), the shape of wind-worn trees and bushes (where there were any, in the taiga), and the behaviour of wildlife.

Several decades later, Darwin published “Origin of certain instincts” in Nature. A Weekly Illustrated Journal of Science 7 (3 April): 417-418. He writes: “With regard to the question of the means by which animals find their way home from a long distance, a striking account, in relation to man, will be found in the English translation of the Expedition to North Siberia, by von Wrangell. He there describes the wonderful manner in which the natives kept a true course towards a particular spot, whilst passing for a long distance through hummocky ice, with incessant changes of direction, and with no guide in the heavens or on the frozen sea. He states (but I quote only from memory of many years standing) that he, an experienced surveyor, and using a compass, failed to do that which these savages easily effected. Yet no one will suppose that they possessed any special sense which is quite absent in us. We must bear in mind that neither a compass, nor the north star, nor any other such sign, suffices to guide a man to a particular spot through an intricate country, or through hummocky ice, when many deviations from a straight course are inevitable, unless the deviations are allowed for, or a sort of “dead reckoning” is kept. All men are able to do this in a greater or less degree, and the natives of Siberia apparently to a wonderful extent, though probably in an unconscious manner. This is effected chiefly, no doubt, by eyesight, but partly, perhaps, by the sense of muscular movement, in the same manner as a man with his eyes blinded can proceed (and some men much better than others) for a short distance in a nearly straight line, or turn at right angles, or back again. The manner in which the sense of direction is sometimes suddenly disarranged in very old and feeble persons, and the feeling of strong distress which, as I know, has been experienced by persons when they have suddenly found out that they have been proceeding in a wholly unexpected and wrong direction, leads to the suspicion that some part of the brain is specialised for the function of direction. Whether animals may not possess the faculty of keeping a dead reckoning of their course in a much more perfect degree than can man; or whether this faculty may not come into play on the commencement of a journey when an animal is shut up in a basket, I will not attempt to discuss, as I have not sufficient data.”

Darwin continues: “I am tempted to add one other case, but here again I am forced to quote from memory, as I have not my books at hand. Audubon kept a pinioned wild goose in confinement, and when the period of migration arrived, it became extremely restless, like all other migratory birds under similar circumstances; and at last it escaped. The poor creature then immediately began its long journey on foot, but its sense of direction seemed to have been perverted, for instead of travelling due southward, it proceeded in exactly the wrong direction, due northward.”

Darwin was a superstar of the secular religion of science; he implicitly compares the Aboriginals of Siberia to different species of birds and bees with instinctive navigational abilities.

It is worth repeating that Darwin says: “Yet no one will suppose that they possessed any special sense which is quite absent in us.” His transformation of the tacit knowledge of Aboriginals into unreflective, instinctive navigation means moving it to a far lower ranking in the knowledge hierarchy. It also means he was simply unable to grasp how these “savages” of Siberia could possibly produce knowledge that was superior to “our” (white European) scientific knowledge.

Darwin may not have realized it at the time, but he is actually comparing two different systems of knowledge. Although he assumes one of these systems is due, probably, to an unconscious mental process, he can’t dismiss it, since it results in valid knowledge. He can only degrade it. Darwin’s musing on the instinctive navigational ability of “savages” shows the conceptual flaws of the pyramid-like hierarchy of knowledge – a concept placing “our” science above “savage” tacit knowledge.

This brings me in a roundabout way to Muir Gray, whom I mentioned in a recent blog. A leading proponent at Oxford University of both Evidence-Based Medicine and Evidence-Based Healthcare, Muir has written widely on the three kinds of generalizable knowledge in healthcare: knowledge from data analysis; knowledge from research; and knowledge from experience, which may not be written down – in other words tacit knowledge. Moreover, in the 2nd edition of his book Evidence-Based Healthcare (2001), he presents (p. 319) a fascinating graph showing two very different paradigms of medical learning (i.e. training), one old and the other new. I will show why this is relevant to polar exploration in a moment.

The old learning paradigm was knowledge-based; intuition was very powerful; one learned from received wisdom; learning was almost “complete” at the end of formal medical training – only a finite amount of knowledge could be absorbed.

Muir contrasts this with the new learning paradigm, which is problem-based, and emphasizes the importance of knowing what one does not know, the ability to generate and refine a question, and the search for, appraisal of, and action on the evidence to solve it. This new learning paradigm also emphasizes the importance of questioning received wisdom. Learning itself is a life-long process – there is always new knowledge to be absorbed; learning involves complementing experience with knowledge from research.

Now, before wandering too far away from polar exploration, which is where I started this blog, experiential knowledge can be of great practical benefit, but when it is tacit or undocumented (like Kazakh and Yakut or Sakha knowledge about navigation), a person relying solely on written knowledge, whether manuscripts or books, will not think of accessing it.

Von Wrangell was a polar explorer, who learned from Aboriginals first-hand; Darwin comments on what he sees in von Wrangell’s exploration narrative, then transforms it because he must have assumed Aboriginals had intellectual limitations, which is a racist assumption.

What bearing does this have on my film, The Blinding Sea? Actually, a lot.

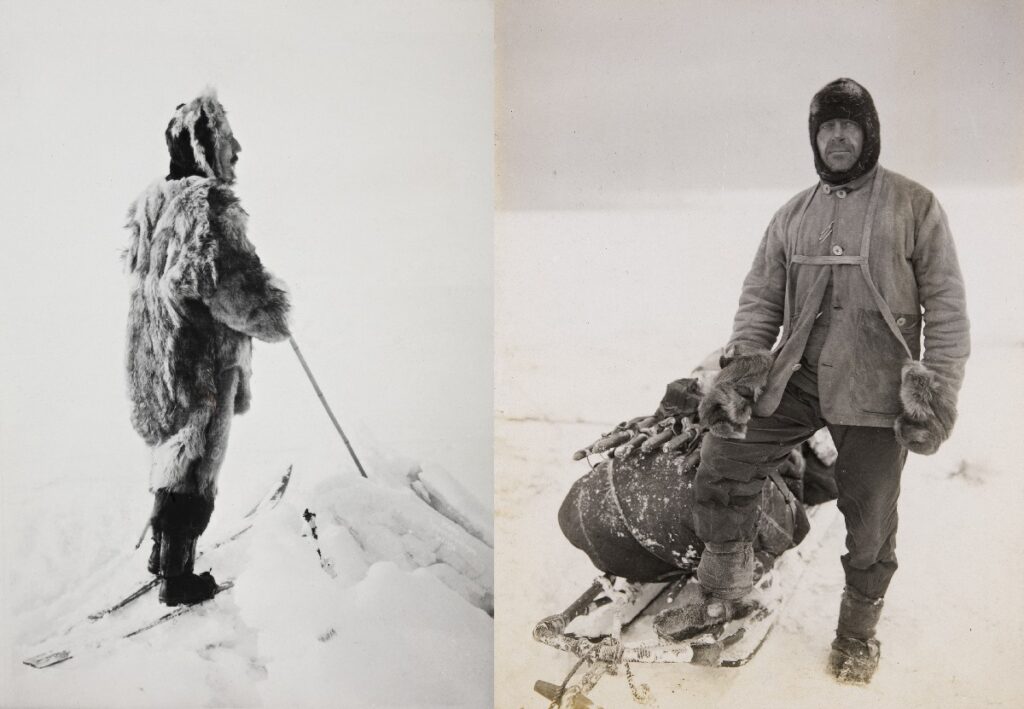

Access to Inuit knowledge helps explain Roald Amundsen’s success in December 1911. It means he favoured the new learning paradigm described by Muir Gray, and did not place Inuit knowledge on a low rung of some overall hierarchy.

Lack of access to Inuit knowledge helps explain Robert Falcon Scott’s catastrophic failure in January-March 1912. It seems clear Scott favoured the old learning paradigm, that is, he learned from received wisdom; his learning was almost “complete” at the end of his training; and he only needed to absorb a finite amount of knowledge. He did not have the chance to learn Inuit tacit knowledge in person, and I wouldn’t want to jump to conclusions about the reason for that. He may simply have lacked the opportunity, or Sir Clements Markham and others providing him with guidance may have steered him away from Inuit knowledge. In the lead-up to the Discovery expedition, Scott accessed other knowledge, mostly in manuscripts and publications, and the Discovery expedition does not seem to have expanded his mind about sources of knowledge. During the Terra Nova expedition, this written knowledge ended up being of far less practical benefit than Inuit knowledge would have been – vital knowledge about polar nutrition, clothing, lodging and dog-sledding.