Virginia Postrel has written the best book I know on glamour. I occasionally exchanged emails with her while making The Blinding Sea.

She says: “Glamour is an imaginative process that creates a specific emotional response: a sharp mixture of projection, longing, admiration, and aspiration. It evokes an audience’s hopes and dreams and makes them seem attainable, all the while maintaining enough distance to sustain the fantasy.”

She told me some people find polar explorers to have been glamorous, particularly aviators. But actually, the Belgica, beset in the polar ice during the long Antarctic night, was the scene for a bizarre Beauty Contest in May 1898, which put the focus on a completely different kind of glamour.

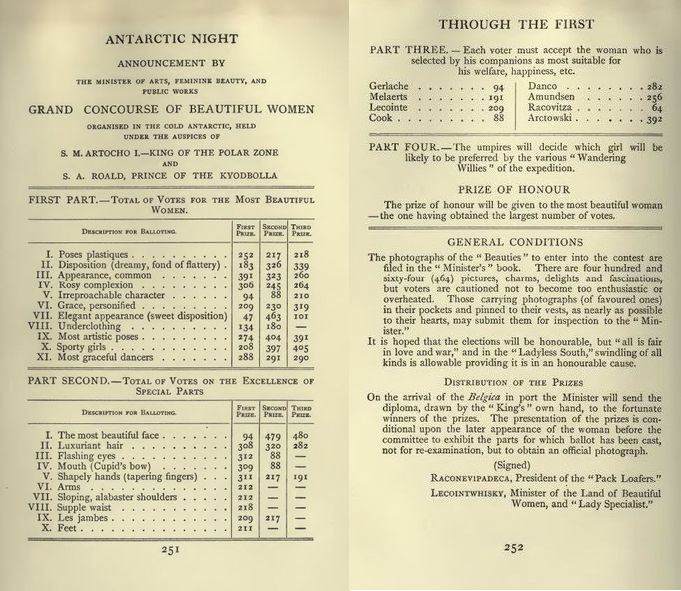

I mention this in The Blinding Sea because every officer writing about his experience during the expedition devoted a few pages to the event, and it was in striking contrast to their rather mournful day-to-day existence.

The Beauty Contest was Roald Amundsen’s idea for cheering up the officers. Remember, polar exploration at the time was a male preserve. No women were present in Antarctica.

Amundsen proposed that the officers go through 500 journal illustrations of women in the ship’s library, and vote on which woman was the most beautiful of all. Of course, Belle Époque illustrations would show well-known dancers and actresses on the public scene. The officers accepted the challenge, and knew, for a brief moment, that mixture of projection, longing and fantasy described above by Virgina Postrel.

At a distance of some 16,000 km. from Belgium, the officers were in no position to communicate the results of the contest to anyone, let alone crown the winner! Consider that the Belgica was the first expedition ever to overwinter in Antarctica. They had already lost one crewmember, Carl Wiencke, washed overboard by a rogue wave the previous summer. They were soon to lose an officer, Émile Danco, to heart failure. As they drifted in the ice-pack of the Bellingshausen Sea, they heard the relentless thundering and screeching impact of ice on the ship’s wooden hull; they sometimes heard whales moaning and blowing in the darkness; they were emotionally starved.

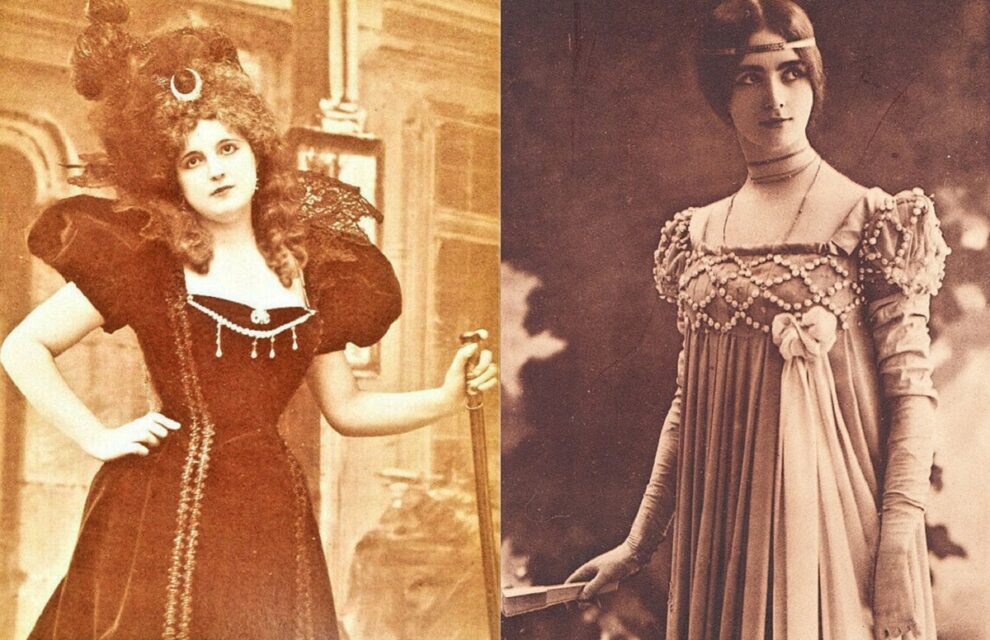

The women pictured in illustrated journals of the time were some of the first celebrities of modern times. One woman who got a lot of votes was Clara Ward, an American exotic dancer who performed in a flesh-coloured body suit, and who had married a Belgian prince. She is pictured in the feature image at the top of this blog, on the left, and at the bottom of this blog.

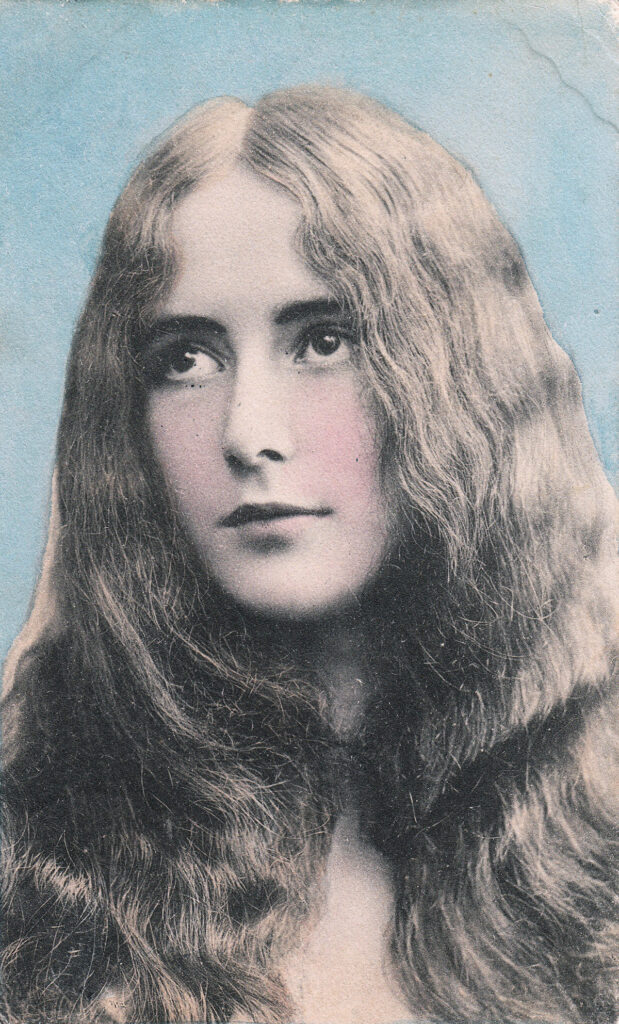

The woman who got Amundsen’s vote was Cléo de Merode, an Austrian/French baroness and dancer. She is pictured in the feature image at the top of the blog, on the right, and immediately below:

Cléo de Merode had created a sensation at the Paris Salon of 1896, by presenting La Danseuse, a statue by Alexandre Falguière for which she had posed nude, although she later denied ever having posed for it. Research by French art historian Anne Pingeot in the Falguière archives demonstrates conclusively that Cléo de Merode did pose nude for the sculptor. She was very good at managing scandal, as a way of building her brand and keeping her iconic image in the headlines. She knew great success as an exotic dancer in Europe, wearing a series of elaborate costumes, some from Cambodia, although her American tour was pretty much a flop.

From our perspective nowadays, Clara Ward and Cléo de Merode were able to capitalize on public fantasies, whether male or female, but they also assumed their own sexuality, at a time when Europeans were severely repressed. These two women were in no way victims of the iconic image they presented to an adoring public: on the contrary, they cultivated that image in a very businesslike manner, by making their beauty into a commodity, becoming postcard stars, mass-producing their likeness and selling it like hotcakes all over the world.

Cléo de Merode was rumoured to be the mistress of the far older King of the Belgians (40 years older). Her passport to fame and fortune seems to have been the scandal she stirred up after posing for Alexandre Falguière’s statue.

The Antarctic Beauty Contest was an exercise in self-deprecation. The descriptions of physical features in Cook’s book (shown above) strike us today as grotesque. The event actually serves as an indication how lonely and frustrated the Belgica officers were during the long polar night – how challenging they found it to be confronted on a daily basis with the prospect of sudden death.

I doubt any of the officers felt happier or brighter once Amundsen’s Beauty Contest was over. Depression was hitting the men hard, now that the sun had dropped below the horizon for two unbroken months of darkness. The expedition doctor, Frederick Cook, was experimenting with light therapy as a remedy for depression – what we now call Seasonal Affective Disorder. This was surely a more practical remedy than flipping through illustrated journals in the ship’s library.