I recently posted a blog on my direct ancestor Mary Osgood, of Andover, Massachusetts (on my mother’s side). In 1692, she confessed under duress to being a witch during the Salem witchcraft trials, but then she recanted and was released after three dreadful months in the witches’ prison.

Now I am wondering about Guillaume Trahan – my first French-speaking direct ancestor in North America (on my father’s side). Originally from St-Pierre de Montreuil-Bellay, then Borgueuil in Touraine, he married Françoise Corbineau in Saint-Étienne-de-Chinon in 1627. Together, they left La Rochelle, France on April 1, 1636, on board the ship Saint Jehan, bound for Port-Royal in Acadia (modern-day Nova Scotia), where they settled.

A few things are worth mentioning about him. He had got into trouble in France, by cutting down trees without authorization, in a forest that apparently belonged to the all-powerful Cardinal Richelieu. A court judgment of the time notes: “le dict TRAHAN 20 livres d’amende et soixante dix livres pour la valleur et estymation du jeune bois qui estoit en deux arpents qu’il a fait arrachez dont partie a esté trouvée en sa maison et oultre en quarante livres pour les domaiges et intêretz.” That is, “The said TRAHAN must pay a fine of 20 livres and 70 livres to make up for the two acres of new-growth trees he cut down and stored in his house, in addition to four livres in damages plus interest.” (This sum of 94 livres may have been equivalent to 30 days of skilled labour.)

France was living through social, religious and economic upheaval, and the prospect of a simpler life in Acadia must have appealed to him, despite simmering tensions between New France and New England. At Cardinal Richelieu’s behest, Isaac de Razilly recruited Guillaume and 300 other colonists to settle the young colony at Port-Royal.

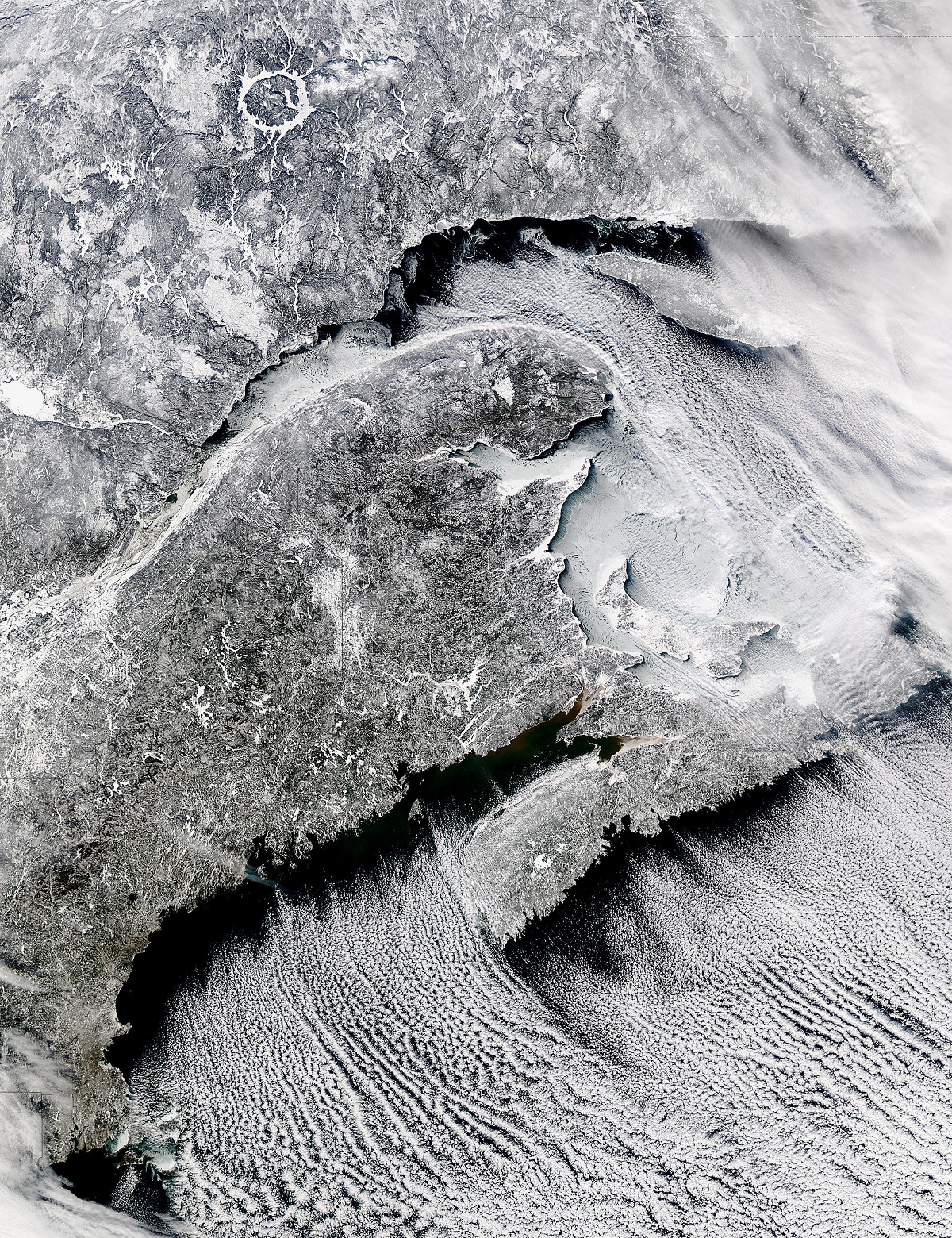

Acadia is a culture bound to the sea, so even if Port-Royal is on the bank of a river, some way inland from the Bay of Fundy, Guillaume Trahan had to adapt to a sea culture. Moreover, the Acadians became a kind of indigenous culture, very much rooted to their new region, which meant forming alliances with Mi’kmaq and Maliseet Indians, and withstanding the on-again/off-again occupations of Acadia by armies from New England.

By trade, Guillaume Trahan was an edge-tool maker. He could also read and write. He improved his condition over the years.

By 1654, Guillaume Trahan was a syndic or property manager at Port-Royal. In this capacity, he had to sign the act of surrender of Port-Royal, since in August of that year it was captured by Robert Sedgwick, at the head of 300 British soldiers and volunteers. Sedgwick was a Puritan from Massachusetts, major-general of the colony there, and a wealthy merchant.

According to Brenda Dunn, author of A History of Port Royal/Annapolis Royal 1605-1800 (Nimbus Publishing), “The soldiers at Port-Royal, who numbered about 130 … put up a brief defence against Sedgwick. Setting up an ambush between the landing site of the English troops and the fort, the Frenchmen fired on the attackers but proved no match for the experienced British. The French soon ‘took their heels to ye Fort.’ On August 16 the fort surrendered. The articles of capitulation were signed abord Sedgwick’s ship Auguste, anchored opposite the fort. Sedgwick granted honourable terms , allowing the defenders to march out of the fort with flags flying, drums beating, and muskets at the ready. … The capture of Port-Royal obviously had an impact on the French settlement that had grown up around the fort. During the attack Sedgwicks men had slaughtered the settlers’ livestock. By the terms of the capitulation, which Guillaume Trahan signed on their behalf, the settlers were offered a ship to return to France. Those who chose to remain were permitted to retain their land and belongings and were guaranteed religious freedom.”

Despite these dramatic events, Guillaume Trahan and his wife decided to remain in Acadia. He eventually remarried when his first wife passed away, and he seems to have died in Port-Royal in 1684. After a few generations, some of his descendants (and my direct ancestors) moved to Quebec, so they were fortunate to escape the English mass deportation in 1755 of Acadians to the Carolinas, Louisiana, Saint-Domingue (modern-day Haiti), Devil’s Island in French Guiana and France itself. Scholars are still debating whether this was ethnic cleansing or genocide.

In my début novel Mind the Gap, I name the heroine Chloé Trahan after my 17th-century ancestor Guillaume.