According to the ancient Greek philosopher Heraclitus, life is in a state of flux.

“We both step and do not step in the same rivers,” he writes. “We are and are not.” (Fragment B49a).

Because water in its liquid state keeps moving, rivers renew themselves. They are never the same, from one moment to the next.

I love this metaphor, and I imagine Heraclitus applying it to the Cayster, a little meandering river running by his home town of Ephesus, in Asia Minor. The river is called “Küçük Menderes” in Turkish and “Kaystros” in Greek. In ancient times, it often silted up or changed course altogether.

I wonder what Heraclitus would have thought if he had ever come to Canada!

After all, Canadians deal with ice – practically on a daily basis, from skating rinks to freezing rain, and ice jams to dense multi-year “growlers” drifting on the Labrador Sea. I remember a winter recently when it got so cold the Gulf of St. Lawrence froze completely over, suffocating nine blue whales who couldn’t breathe under the ice.

I took the above photo in the Yukon, while flying over the South Arm of the Kaskawulsh Glacier, in Kluane National Park. The Yukon has one of the world’s largest ice fields outside of Greenland and Antarctica – but climate change is wearing the ice down.

Then there is the interaction of liquid and ice.

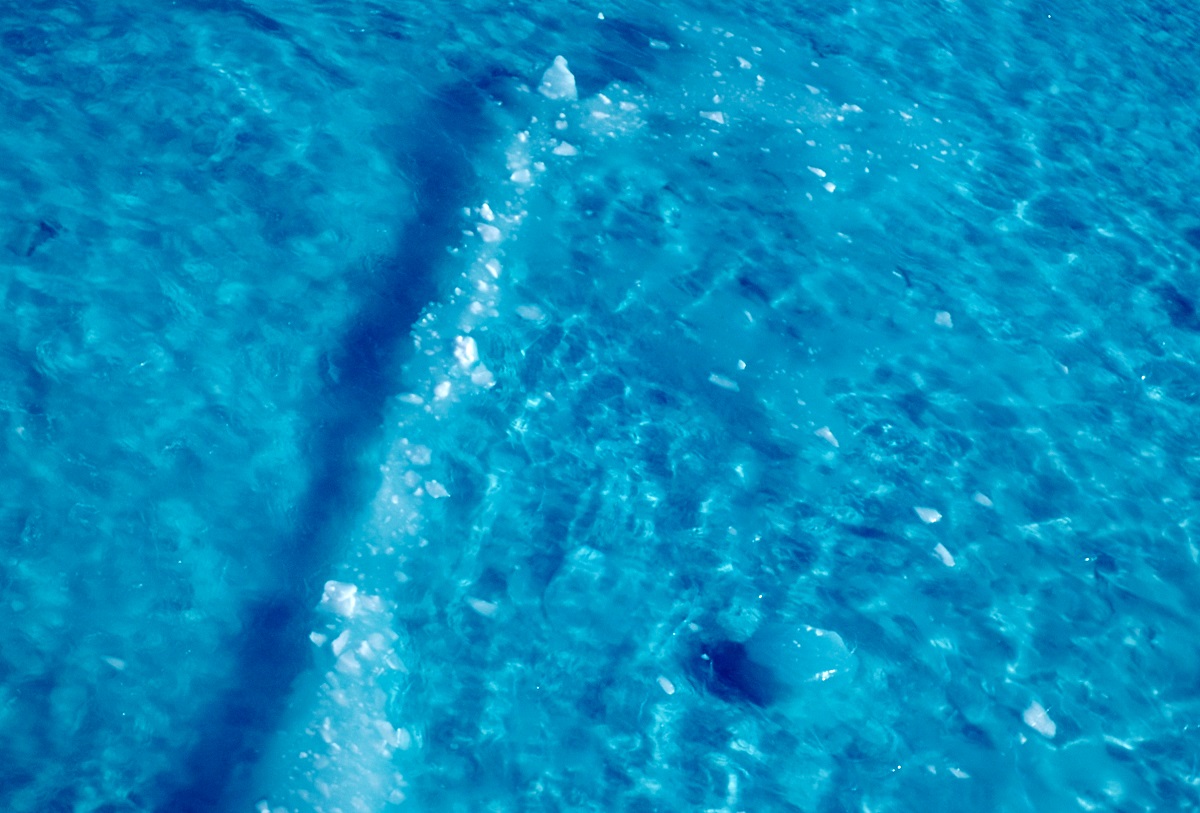

I took this photo on board a ship trapped in the Arctic ice, as we reversed engines in a desperate attempt to break free. The propellers lobbed seawater up onto the ice, turning it turquoise. Here were two states of H2O, one flowing over the other.

Ice is frozen, and in my mind, the word “frozen” also applies to an unchanging person locked into place, rigid, stuck, unbending, unshakeable – not so much from principle as from habit or fear or some law of gravity I don’t know about. I sometimes meet people snug in their belief system who see no need for change.

When you get right down to it, ice, like liquid water, is constantly moving. There may seem no silence quite as total as on a frozen lake. But then … have you ever heard the crack and moan and shudder of lake ice, as plates form and merge, coursing across the surface?

Standing on the Northwest Passage once (the wind chill that evening was -68°C or -90°F), it took me awhile to realize something. No matter how cold it gets, sea ice is porous, and constantly subject to the influence of tides, currents, the wind and gravity. Sea ice is constantly on the move. And within that sea ice, salt is leached out through microscopic brine channels, purifying and hardening the ice.

The climate apocalypse is upon us. Nobody knows how long the great glaciers will last – like the Rhone Glacier, below, which I photographed a few years ago in Switzerland, while preparing a documentary series for CBC Radio and Radio-Canada. I couldn’t help feeling, at the time, that this glacier was a vestige of the last Ice Age, a mute witness of prehistory reaching back to the first stirrings of humanity across Europe.

If Heraclitus had been to Canada, maybe he would have said ice is simply frozen water and there is no need to change his metaphor. As if to say: “We both step and do not step onto the same rivers. Ice is and is not.”