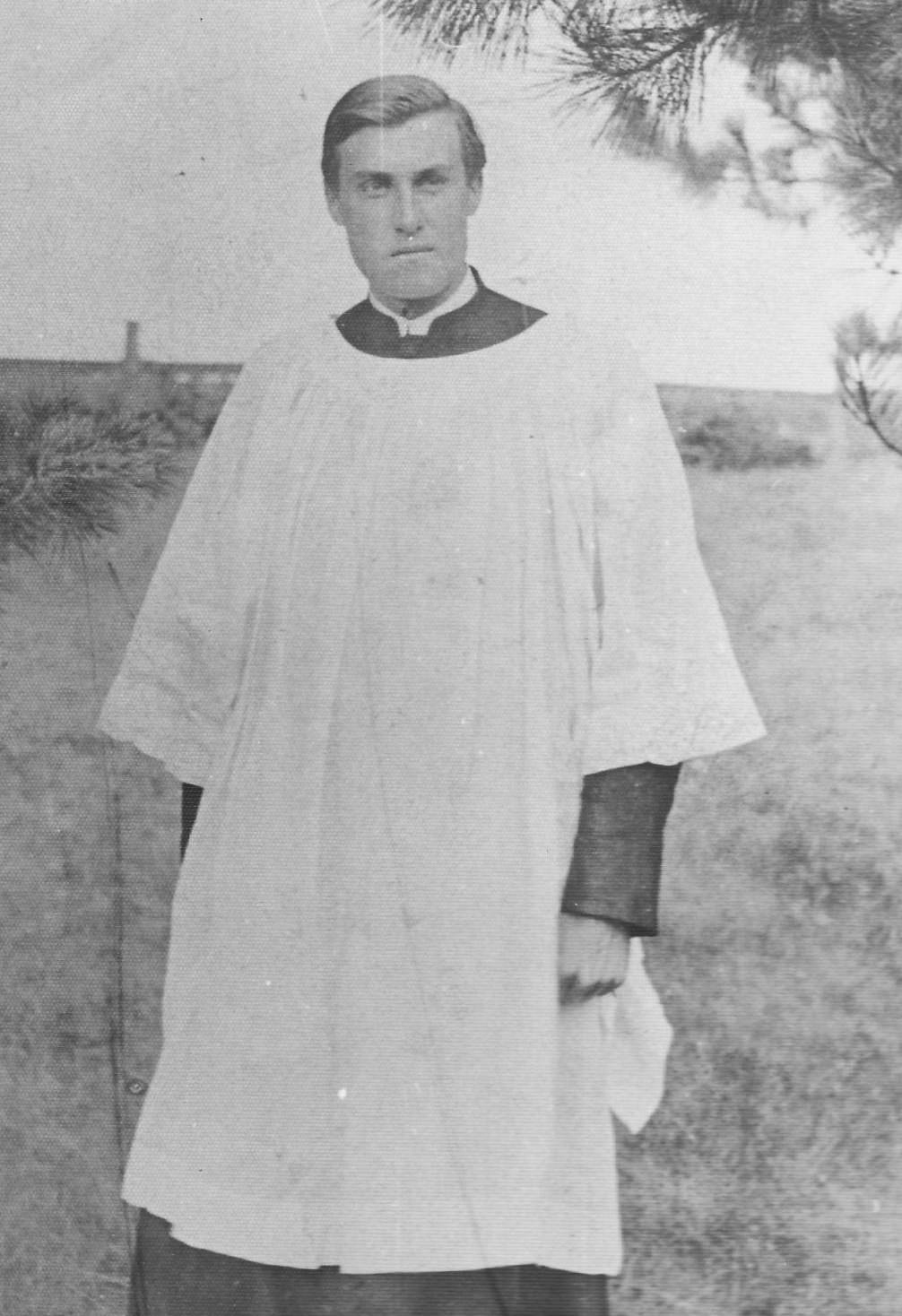

My favourite storyteller? It was my grandfather Frederick C. Grant, who passed away in 1974. Two years before he died, when I was taking care of him, he asked what impression I got from reading books he had written.

“Well, it’s as if I could hear your voice speaking directly to me,” I said.

“George, that’s the greatest compliment you can make to an author. That’s the whole point of writing.”

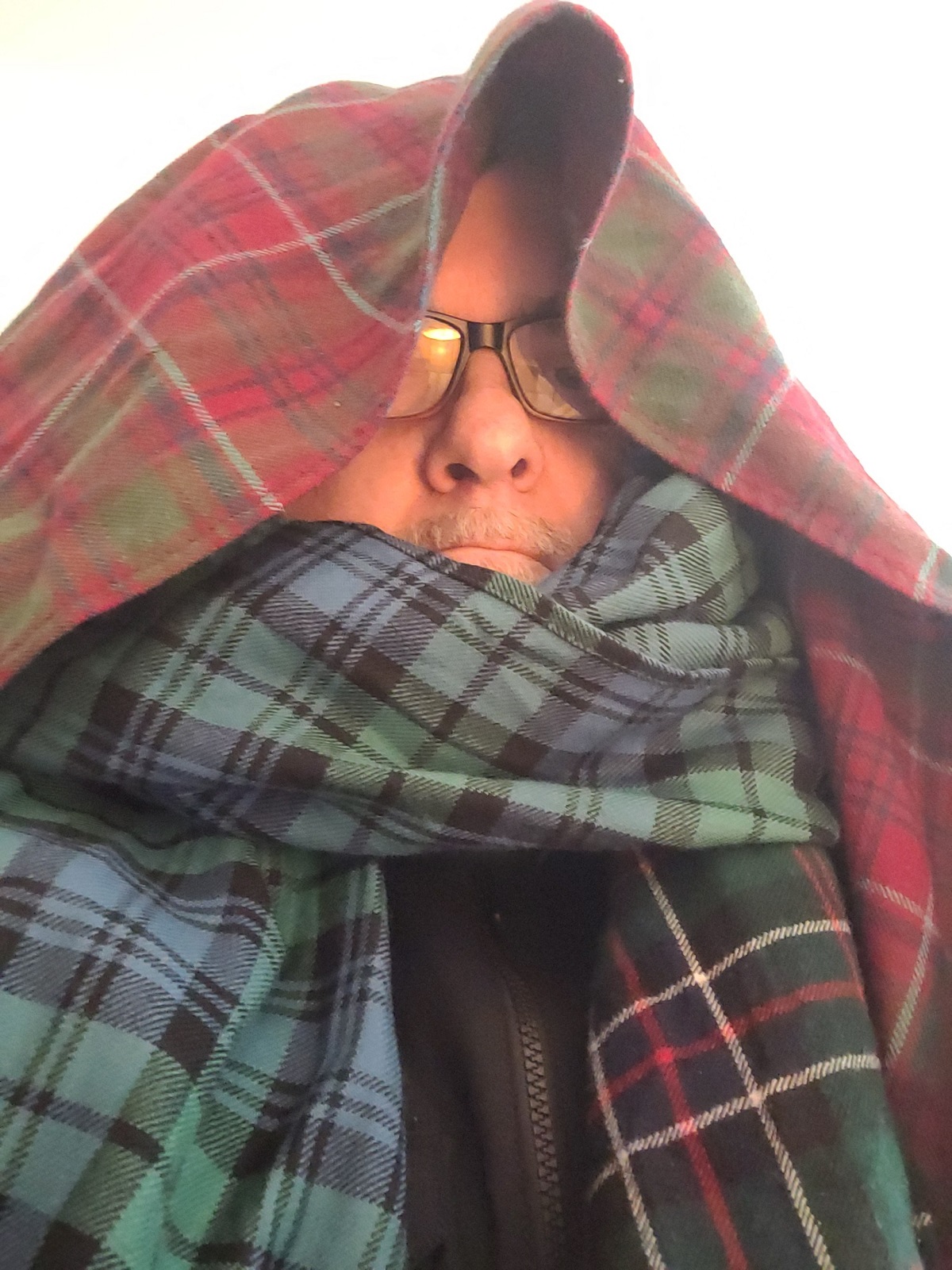

I loved it when my grandfather told me stories about his boyhood in Appleton, Wisconsin and his young adulthood in Evanston, Illinois. These stories have never left me. In fact, he was a born storyteller. His voice is still a daily presence in my life. In the feature image at the top of this blog, taken in 1972, I have just given my grandfather a Karen Bulow wool tie made by Inuit in Pangnirtung, Baffin Island, and he has just given me a Grant tartan wool scarf.

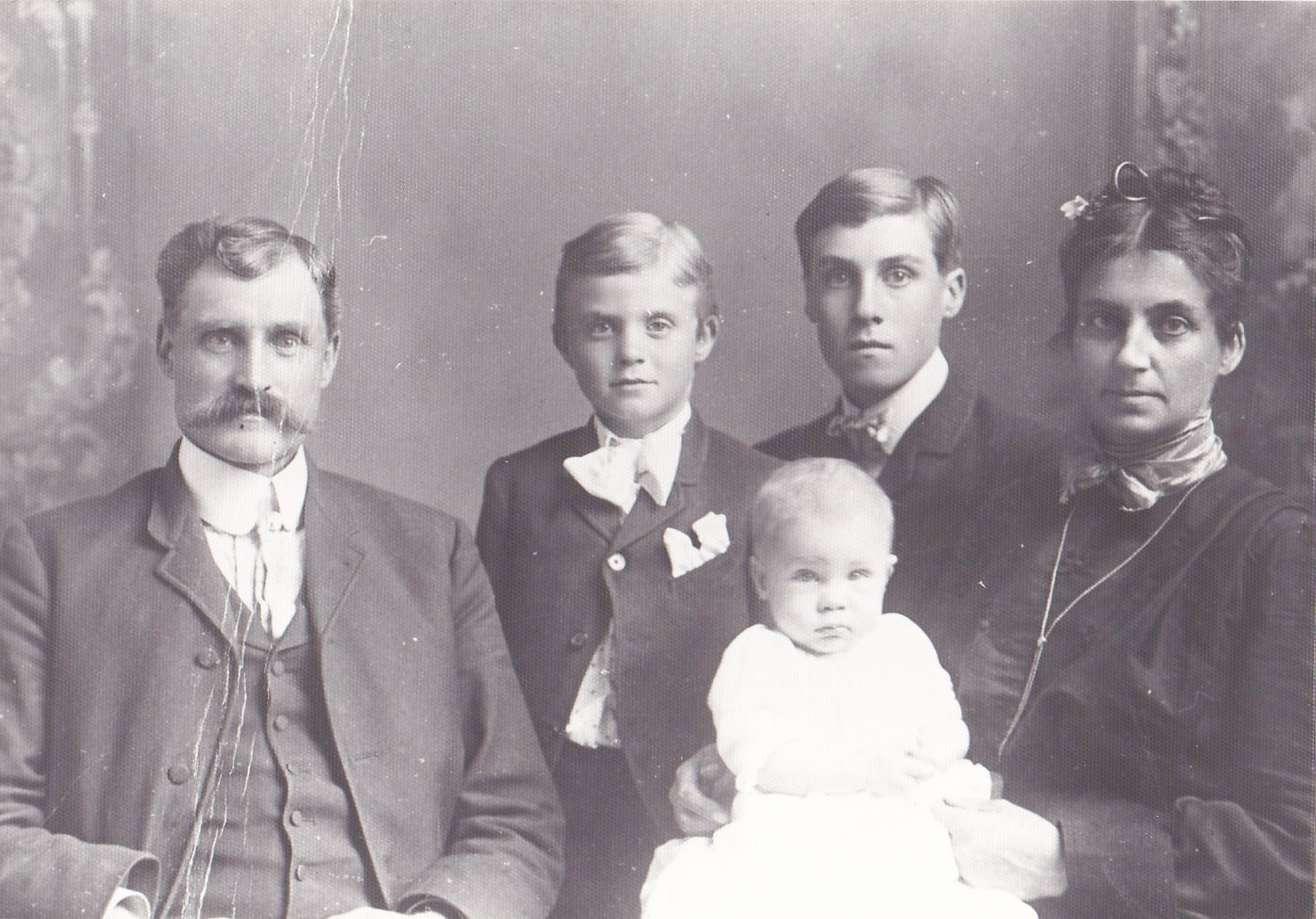

The most moving story Frederick told me went back to 1892, when he was an infant. The story involved his mother Anna Lois Jack Grant, a flock of sheep and a spinning wheel.

I remember, when producing and directing my feature film The Blinding Sea, and letting the camera teach me how to see people and situations properly, that I often thought of my great-grandmother and her spinning wheel. My cameras and her spinning wheel helped both of us create works, reach out to other people, and offer the best of ourselves.

To tell you the truth, I don’t know a great deal about my great-grandmother. I know she and my great-grandfather crossed Canada and America from New Brunswick to Wisconsin, driving their oxen and their cart; I know in the Midwest they discovered they had been completely cheated, because no farm awaited them there, so they headed back to New Brunswick; but then, finding themselves cheated there as well, they returned on muddy trails to Wisconsin. I know she settled in a wood cabin (without a roof) on a farm hemmed in by the forest of Wisconsin; she had some sheep and a barn; and she occasionally met Oneida, whose nation had been deported there from upstate New York in the late eighteenth century.

But now her infant child Frederick, my grandfather, came down with whooping cough, which was often fatal in those years. Anna Grant had provided mutton and wool bedspreads and clothing to nearby native Americans the previous winter, helping them to survive. Suddenly, a medicine man emerged from the forest and offered herbal medicine to save my grandfather’s life.

I picture Anna Grant in her cabin, late at night, with the wind howling outside, just as it is here, this evening in Quebec. We are in the midst of a blizzard. She didn’t just happen to have piles of wool coverings lying around, as if she were running a warehouse. She was a resourceful woman and always kept busy, making woollens herself. One of her prize possessions was the spinning wheel, which enabled her to spin wool from her flock, and clothe and protect her family.

This story was a leitmotiv throughout my youth – yet I was haunted by the feeling that some important details were missing.

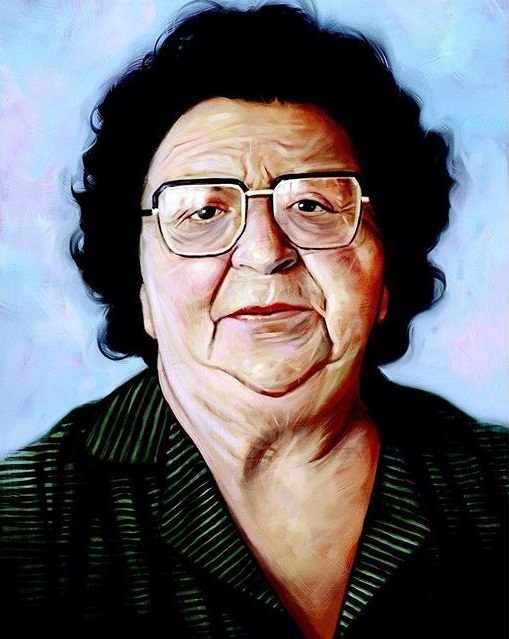

In 1984, ten years after my grandfather died, something happened quite by accident. When interviewing Mary Two-Axe Earley, the Haudenosanee (Mohawk) women’s rights advocate in Kahnawake, near Montreal, I asked all the questions CBC Radio wanted me to put to her, about the 400th anniversary of Jacques Cartier’s first voyage of exploration up the Saint Lawrence River. Then I turned off the tape-recorder and asked her a last question – one just for me.

“Mary, I have always wondered about my grandfather and the way a medicine man saved his life in Appleton, Wisconsin using the roots of plants from the forest.”

She asked me to tell her everything I remembered, in detail.

Her eyes lit up. Then, to my astonishment, she said, “George, I am half-Oneida. My mother was Juliette Smith Two-Axe, an Oneida nurse who died during the Spanish Influenza epidemic. It is clear the medicine man you refer to, in those years, in that part of Wisconsin, was my grandfather, Jacob Smith. The Oneida reservation is about 12 miles from Appleton. Grandfather took me many times into the forest, to show me medicinal plants. What you say conforms exactly to what he showed me in his medical practice. My Mohawk father and grandfather were also medicine men.”

Mary suddenly became a powerful connection to my grandfather, part of the chain of being, and their combined stories connected me to my great-grandmother.

I wrote a poem about what she said, in French, as if she herself were telling me the entire story from a new perspective. (I write interchangeably in French and English.) Here is the poem, in French. If you don’t understand it, please scroll down to the English translation underneath:

Vieille Marie

« Il y a longtemps », dit Vieille Marie aux yeux ardents,

« Il y a longtemps, lorsque l’émouvante plainte du huard s’est arrêtée,

et le caquetage des oies des neiges a disparu vers le Sud,

et les premiers doigts de glace hivernale

sifflaient et craquelaient, s’agrégeant en plaques à travers le lac,

recouvrant sa surface bleue-songe d’un silence aux flèches mortes,

Eh bien Grand-père a émergé doucement des ombres de la forêt en mocassins.

Il connaissait l’histoire de ton peuple :

comment vous aviez marché, fouettant le boeuf,

depuis le grand océan jusqu’au Wisconsin, six lunes durant.

Aviez troqué une ferme dans l’Est contre une vague promesse

dans l’Ouest : une cabane sans toit, ni terre autour.

Il comprenait que ton peuple, tout tremblant de stupeur et de rage,

était reparti rejoindre le grand océan, toujours à pied,

pour subir, impuissants, un échec devant la justice.

Il voyait le nombre de lunes qu’avait pris le retour,

lorsque crasseux, affamés, toujours à pied, vous aviez laissé l’océan,

pour faire une troisième traversée de l’Amérique et regagner la cabane sans toit.

Il voyait que cela vous avait donné peur des ours et loups,

de tout danger invisible.

Du clapotis des vagues bleues. De la foule muette de pins.

De la terre des Oneida,

illuminée la nuit par les feux de mon peuple.

Vous aviez peur de nous aussi, de nos cheveux noirs.

De nos rêves et amours chuchotés. De nos espoirs

Vous aviez peur de nous aussi, de nos cheveux noirs.

De nos rêves et amours chuchotés. De nos espoirs.

« Eh bien Grand-père voyant ton propre grand-père,

ce nouveau-né sifflant, secoué par des convulsions de toux :

voilà l’étrange chant qui annonce le silence de la mort.

Le médecin blanc à lunettes, qui sortait sa futile science

d’un cartable noir rempli d’instruments divers,

qui haussait les épaules et attribuait

cette coqueluche à d’obscurs parasites issus de l’Indien,

disant qu’il ne restait plus rien à faire, sinon prier.

Anna qui sanglotait dans son fauteuil à bascule,

serrant ce bébé agonisant contre son sein,

ce bébé pour lequel elle aussi avait vécu l’agonie.

« Eh bien Grand-père a émergé doucement des ombres en mocassins.

Il était grand et noir comme le corbeau. Il était fort. Il était sage.

Il connaissait le veuf et sa petite fille,

et pourquoi l’ours n’a pas de queue,

Il savait quels lacs n’avaient jamais fait de mort,

et quels lacs avaient noyé et pourquoi.

Comme il pouvait pénétrer le futur,

dans son coeur il pleurait déjà le destin des Oneida.

Mais plus encore, il connaissait les pouvoirs secrets de la Terre

que je ne puis dévoiler : les flûtes, les tambours,

les charmes sacrés qui doivent accompagner la réduction des os

et les remèdes des plantes.

«‘Je viens de faire un songe’ », dit Grand-père à Anna.

Sa voix tremble d’émotion :

il voit que la mort glacée avance sur le petit bébé.

‘Vous êtes arrivés dans la forêt,

dans cette cabane sans toit.

Lorsqu’enfin, à force de lutter, vous ne manquiez de rien,

vous êtes venus jusqu’à notre camp nourrir mon peuple,

nous offrant vos couvertures. Mais là, vous êtes dans le besoin.

Je vois que le médecin de ville n’a rien fait.

Voulez-vous faire confiance à ma médecine ’?

Le moment de vérité est arrivé.

Anna doit choisir :

entre l’orgueil de l’homme à lunettes

et la sagesse des anciens.

La dureté de la vie dans cette terre à outrance lui semble insoutenable.

Faiblement elle fait signe que oui.

« Eh bien Grand-père rejoint doucement les ombres en mocassins,

Arrache les herbes et racines que connaissent seuls les sorciers.

Il revient marmonnant mots et incantations que je n’ose répéter,

afin de refaire l’unité de la Terre.

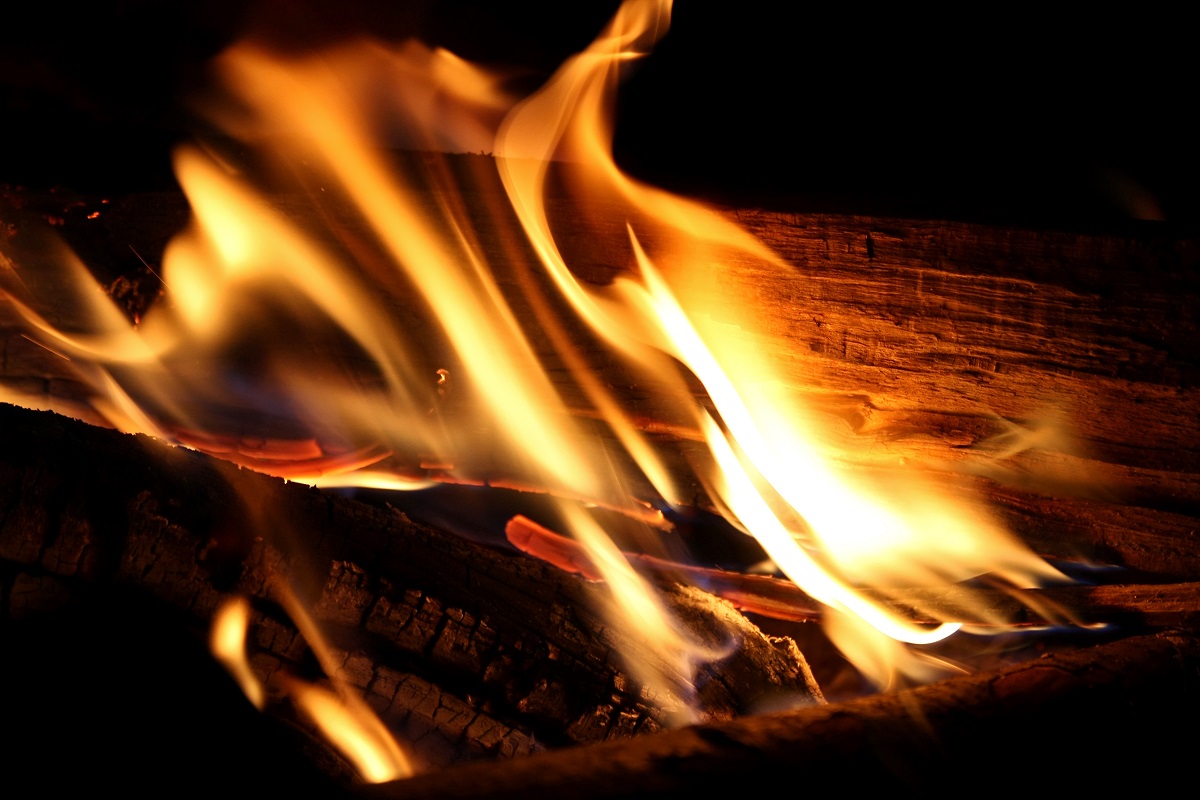

Il bâtit un feu, dont les flammes crachent des étincelles bleues

jusqu’en haut des pins sentinelles.

Il prépare un bouillon d’herbes et de racines,

se mettant à nu, exposant sa poitrine aux flammes,

se tenant le plus près possible.

Puis il serre le bébé dans ses bras, lui versant du bouillon dans la gorge.

Les nuits d’hiver sont longues.

Grand-père se penche près des flammes, et verse du bouillon dans la bouche de l’enfant,

serrant son petit corps jusqu’à ce que les hurlements s’estompent enfin vers

l’aube.

La fièvre a baissé. C’était il y a longtemps.

« Il y a longtemps », dit Vieille Marie aux yeux ardents.

« Il y a longtemps, un bébé a appris le sacrifice et l’amour.

Voilà un don que tu as reçu des Oneida. Ce don habite ton sang et tes os.

Raconte à tes enfants d’où ils viennent,

avant de rejoindre à jamais, à ton tour, les ombres de la forêt ».

Old Mary

“A long time ago,” said Old Mary with the fiery eyes,

“A long time ago, when the rippling laughter of the loon fell silent,

and the cackling of snow geese disappeared southwards,

and the first fingers of winter ice

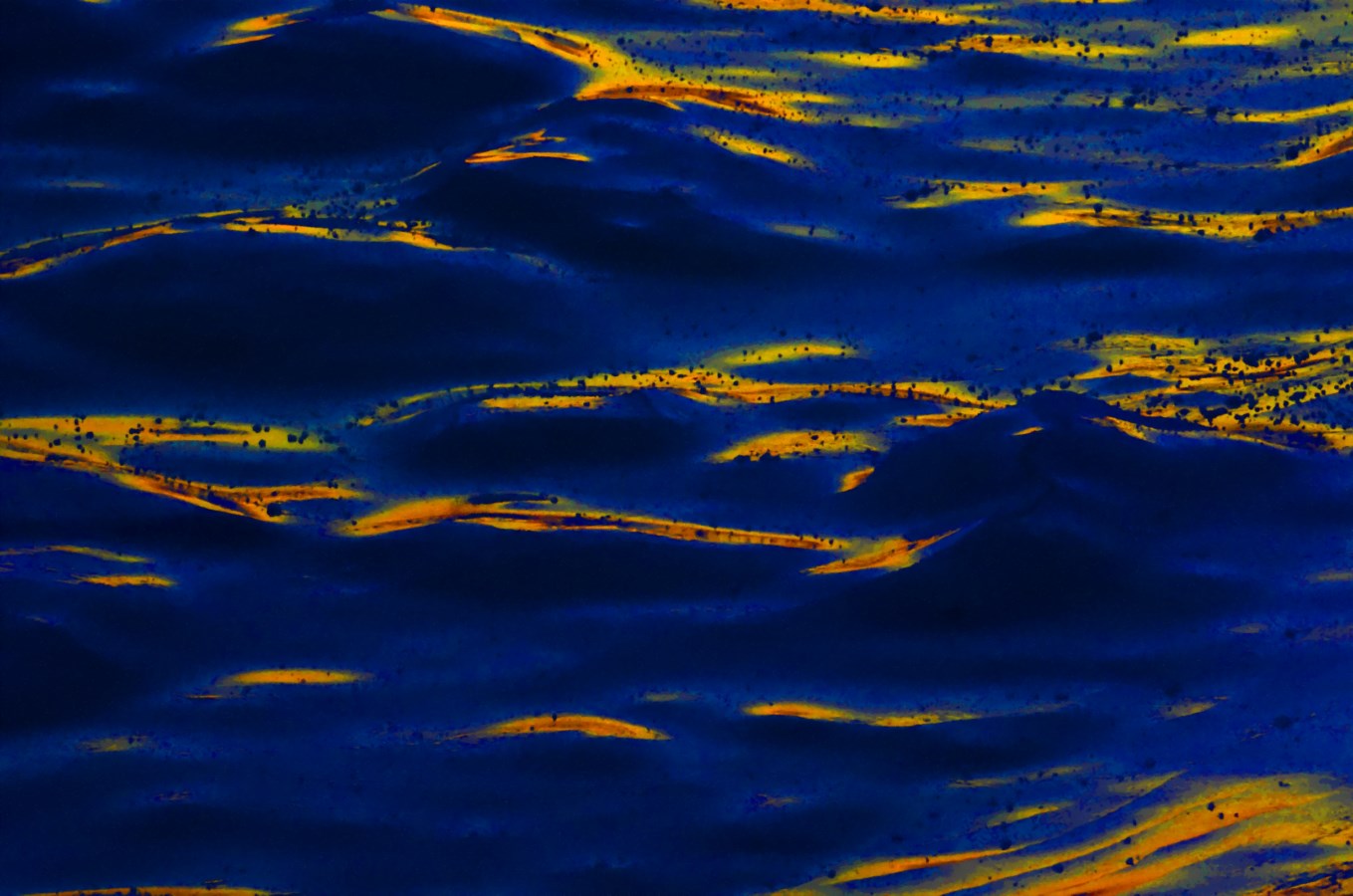

whistled and crackled, forming plates across the lake,

covering its blue-dream surface with a silence like dead arrows,

Well, Grandfather slowly emerged from the shadows of the forest in moccasins.

He knew the story of your people:

how you had walked, whipping the oxen,

from the great ocean to Wisconsin, during six moons.

How you had traded a farm in the East against a vague promise

in the West: a cabin without a roof, on a small parcel of land.

He understood that your people, trembling with stupor and rage,

Had headed back on foot, all the way to the big ocean,

to be cheated once again, powerless, before a judge.

He saw the number of moons it had taken took for you to return,

filthy, hungry, trudging on foot, leaving the ocean behind,

to make a third crossing of America, to reach the cabin without a roof.

He saw you were afraid of bears and wolves,

of all invisible danger.

The lapping of blue waves. The mute crowd of pines.

The land of the Oneida,

Lit up at night by the fires of my people.

You were afraid of us too, of our black hair.

Our dreams and whispered loves. Our hopes.

“Well Grandfather seeing your own grandfather,

this newborn baby wheezing, shaken by convulsions of coughing:

a strange song before the silence of death.

A white doctor with spectacles, who confined his futile science

to a black bag filled with various instruments,

who shrugged and said,

this whooping cough was caused by parasites borne by Indians,

and there was nothing left to do, except to pray.

Anna sobbing in her rocking chair,

Clutching the dying baby against her breast,

this baby for whom she too had lived through agonies.

“Well, Grandfather slowly emerged from the shadows in moccasins.

He was tall and black like the raven. He was strong. He was wise.

He knew the widower and his little girl,

and why the bear has no tail,

He knew which lakes had never brought death,

and what lakes had drowned and why.

He could see into the future,

And in his heart, he was already mourning the fate of the Oneida.

But even more, he knew the secret powers of the Earth

that I can not reveal: flutes, drums,

the sacred charms that must accompany the reduction of bones

and the remedies of plants.

“‘I just had a dream,’ Grandfather said to Anna.

His voice trembling with emotion:

he saw icy death creeping over the little baby.

‘You arrived in the forest,

Reaching this cabin without a roof.

When finally, through hard toil, you had enough for yourselves,

you came to our camp to feed my people,

offering us wool blankets. Now you are the ones in need.

I see the city doctor did nothing.

Are you willing to trust my medicine?’

“The moment of truth has arrived.

Anna had to choose:

between the pride of the man with spectacles

and the wisdom of the elders.

The harshness of life in this land of extremes was hard to bear.

Slowly she nodded yes.

“Well, Grandfather slowly walked into the shadows in moccasins,

Collecting the plants only medicine men know.

He came back mumbling words and incantations I dare not repeat,

Restoring the unity of the Earth.

He built a fire, whose flames spit blue sparks

to the top of the sentinel pines.

He prepared a broth of herbs and roots,

Stripping his chest bare, and exposing it to the flames,

standing as close as possible.

Then he squeezed the baby in his arms, pouring broth down its throat.

Winter nights are long.

Grandfather leant near the flames, pouring broth into the child’s mouth,

squeezing its little body until the screams finally subsided just before

dawn.

The fever went down. This was a long time ago.

“A long time ago,” said Old Mary with fiery eyes.

“A long time ago, a baby learned sacrifice and love.

This is a gift you have received from the Oneida. This gift dwells in your blood and bones.

Tell your children where they come from,

before you vanish, in turn, into the shadows of the forest.”

***

Oneida historian Gordon McLester told me this medicine man’s name was likely Jacob ‘Doc’ Smith. I recently researched medicinal plants used by the Oneida Nation in Wisconsin to treat whooping cough. One plant stands out because of its antibiotic properties: Goldenseal or Hydrastis canadensis.

It is possible the plant that Jacob Smith used to save my grandfather was Goldenseal (shown above), which is called Hydraste du Canada in French.

This plant also grows in Quebec, where I live. The healing presence of the medicine man and this plant may explain why I am here today. The chains of being across generations also explain why I made The Blinding Sea, which is a film about crossing cultural barriers, with respect, and learning vital knowledge.

My grandfather Frederick told me other stories about his youth. His father Frank Avery Grant was stationmaster in Appleton, and had high hopes of working a farm, in order to give the family more opportunities. But my grandfather told me how the barn once caught fire, and his father’s horses raced into the barn and burned to death. So, it was back to being stationmaster. Perhaps the flock of sheep were an episode in his life.

Another story my Frederick told me was how his parents bought a set of encyclopedias for him, sometime around 1900: he read all the volumes straight through from A to Z, three times. No wonder he would later master eight languages, write twenty books and translate thirty more!

And then there were the race riots in Chicago in July 1919. My grandfather was a minister serving at Trinity Episcopal Church in South Chicago: he brought several black women directly into the sanctuary of the church, and prevented a howling white mob outside from murdering them.

My grandfather, great-grandmother and Mary Two-Axe often visit me in my dreams, and with their soothing voices offer me wisdom.

On the subject of wool, my experiences film-making in Antarctica and Nunavut taught me the meaning of cold. I am not sure I have recovered yet!