I just streamed The Blinding Sea for a week to members of the British Association for Canadian Studies, following which we had a Zoom debate over this past weekend, hosted by Tony McCulloch, President of BACS and Associate Professor of North American Studies at the Institute of the Americas, University College London. The discussant invited to provide a critique of the film was Annis May Timpson at Cambridge University.

In the words of Tony McCulloch, “The Blinding Sea is not only a fascinating film about the polar expeditions of Roald Amundsen: it is also a very significant documentary that underlines the role of the Inuit in teaching the legendary explorer how to survive the extreme climate and terrains with which he was confronted. George Tombs is to be congratulated for producing and directing such an important work and for discussing it so openly and cogently with BACS members at our annual conference.”

Annis May Timpson gave a well-considered critique of the film, drawing on her own extensive knowledge and experience of Arctic Canada. She noted that Roald Amundsen named the Inuit who had made huge contributions to his polar education, including Teraiu, Talurnakto and the Owl. She mentioned the socioeconomic background of polar explorers, whose ships, advanced technologies and financial advantages made them men of power once they arrived in the North, no matter what their intentions may have been. She said the exclusively male aspect of polar exploration a hundred and more years ago was limiting, since it left little room for women and their accomplishments, including Inuit women.

I said that women are vectors of knowledge in every society in the world, and are even the main vectors of knowledge. By all accounts, including Inuit oral traditions, Amundsen had respectful friendships with a number of women in Nunavut – women who had a major impact on him during the weeks and months he travelled with them and their families.

James Kennedy at the University of Edinburgh asked whether Scandinavian explorers were more likely than British explorers to be aware of Aboriginal knowledge. I said we should be careful not to generalize about Britons, since some British explorers, such as Sir John Ross, his nephew Sir James Clark Ross and also Dr. John Rae, were able through long years of interactions to learn from Aboriginal knowledge systems, whereas other British explorers, such as Sir John Franklin and Robert Falcon Scott, were clearly unable to learn from Aboriginals. Also, Ernest Shackleton is considered British in Britain but has, with the passage of time, come to be considered Irish in Ireland. I mentioned that some explorers were hampered a century and more ago by the view that European science was at the very top of a hierarchy of knowledge, which considered Aboriginal knowledge as marginal or peripheral, whereas expeditions in the polar regions stood to benefit from access to the knowledge systems of polar peoples. I cited Amundsen as an example of someone who placed Aboriginal knowledge on an equal footing with science.

The conversation moved to the behaviour of characters in the film. I described Amundsen as a driven person, capable of empathy and understanding, but also someone with a harsh and selfish streak in his personality, as evidenced, for example, by the way he summarily sent two Chukchi girls he had adopted back to Siberia after going bankrupt.

We discussed the research I undertook for the film, as well as the experience of getting to know polar families, filming in the Arctic and Antarctic, and pulling such an enormous mass of material together. I enjoyed this gracious and frank sharing of views during the debate at the BACS Conference, which was my first back-and-forth event with a knowledgeable British film audience.

Annis May Timpson made some positive suggestions for further research, which are all the more valuable now that I am writing WildTrekker, an expedition biography of Amundsen, which I will eventually co-market with the film.

Then she asked a very insightful question, which took me a moment to answer. What could I say about the last line of the credits … in which I dedicate the film to Marie Frenette? I have to say, it is very unusual for someone in the audience to read through the film credits with such care!

I explained Marie sings beautifully on the soundtrack of the film. Marie also helped me in every way possible during the production: she provided wisdom on how to manage situations, led sessions with jazz musicians, and offered untiring technical support in her audio-recording studio. In fact, Marie helped me through thick and thin during the making of The Blinding Sea. Without her, I could never possibly have completed the film, so it is natural that I dedicate this work to her.

+++

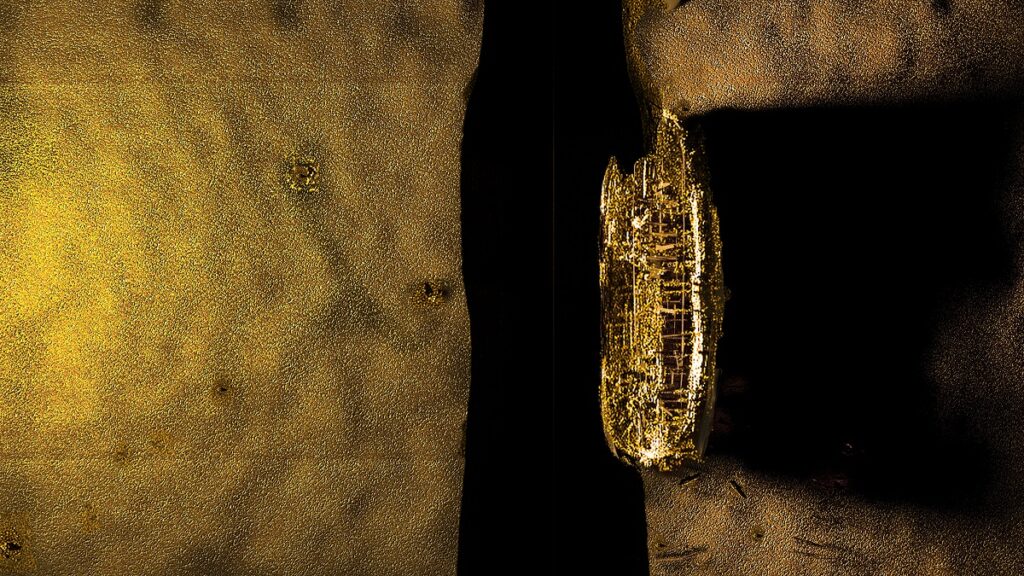

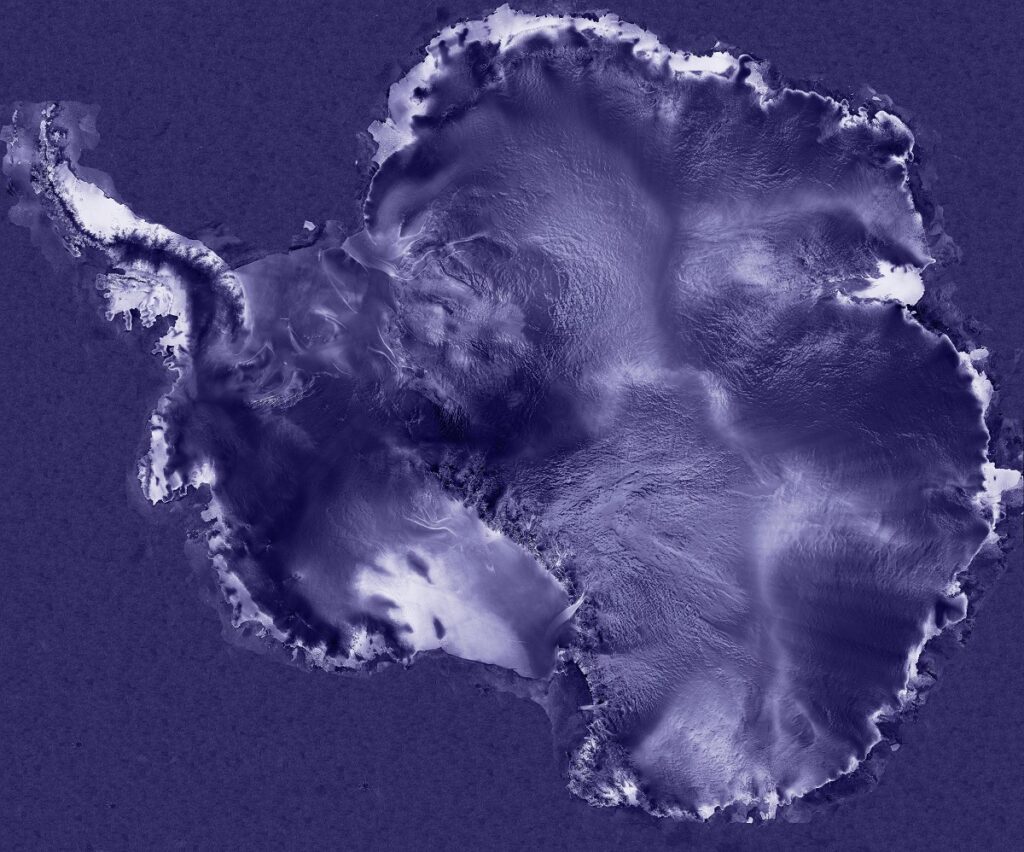

The featured image at the top of this blog shows, on the left, Roald Amundsen in furs, and on the right, his rival Robert Falcon Scott mostly in wool. The two men went head-to-head in the 1911-1912 race to the South Pole.