During the current pandemic, the question of how to reach public audiences with properly validated information about COVID-19 is daunting.

On a daily basis, we hear often contradictory guidance from political leaders, public-health authorities, pharmaceutical companies and other opinion-makers. We read or watch journalism that highlights weaknesses, threats and harms more often than strengths, opportunities and benefits. Some people indulge in conspiracy theories and other disinformation on the web, which quite deliberately feed paranoia about mass deaths and dying, unwanted side effects of vaccines, and the nature of COVID-19 in the first place.

Public information campaigns need to keep the public on course to overcome the pandemic through a combination of knowledge, vaccines and concerted, responsible behaviour. We all have a stake in survival.

This situation reminds me of an assignment I did a few years ago at Oxford University, in the MSc programme in Evidence-Based Health Care (EBHC). Unfortunately, the MSc programme was abruptly shut down after my first year. Life moved on, and I did not pursue the degree, once the programme started up again several years later.

My assignment focused on public information campaigns and their need to acknowledge the gap between health science and journalism. I drew on my own experience as a print, radio and television journalist ever on a quest for knowledge.

I have long been concerned how to raise standards of information in journalism.

Back in 1919, Walter Lippmann wrote that journalism was being practised by “untrained accidental witnesses” who needed more of “the scientific spirit… There is but one kind of unity possible in a world as diverse as ours. It is unity of method, rather than aim; the unity of disciplined experiment… It does not matter that the news is not susceptible of mathematical statement. In fact, just because news is complex and slippery, good reporting requires the exercise of the highest scientific virtues.”

Journalists work in a context without clearly articulated rules of evidence. Yet they often use rules of thumb grounded in their values, even if these rules operate at an intuitive level.

Journalists reach vast public audiences through the mass media. Can they play a useful role in disseminating Evidence-Based Health Care information and in critically appraising medical literature? The problem is, they face several structural challenges: the quest of the newsworthy, the temptation to hype health stories and highlight anecdotal aspects such as human interest at the expense of scientific evidence, and finally market pressures which often dictate editorial policy.

The mass media are eager to tell “the greatest story ever told,” in the narrative mode. Story-telling is all-important. But in order to play a useful role in disseminating Evidence-Based Health Care information, journalists need to be properly engaged, trained, motivated and supported, in order to become true “knowledge translators” and/or “knowledge brokers.”

And this means learning how to create compelling narratives based on valid evidence. It also means that journalists need to understand that science is a public, self-correcting enterprise.

Whereas the public craves certainty, the pandemic has taught us more about scientific uncertainty than any other event in recent memory.

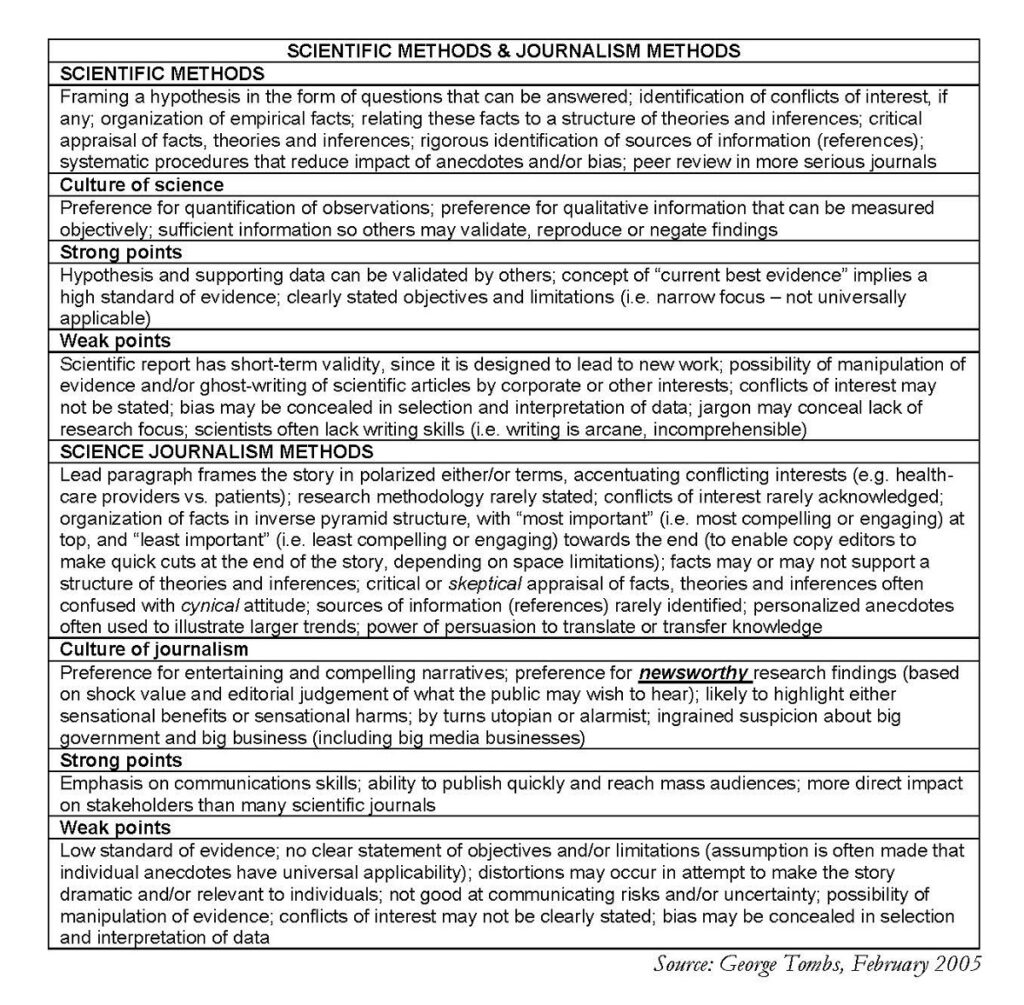

I developed the following table for the assignment at Oxford, as a way of contrasting the methods of evidence-based science and journalism:

Meanwhile, Evidence-Based Health Care researchers produce important information. Yet this information is not disseminated as widely or as effectively as it deserves to be. EBHC information is sometimes unable to compete in the wider media marketplace, given the power of the mass media to inform and sometimes to misinform. Some health care researchers also resort to hype!

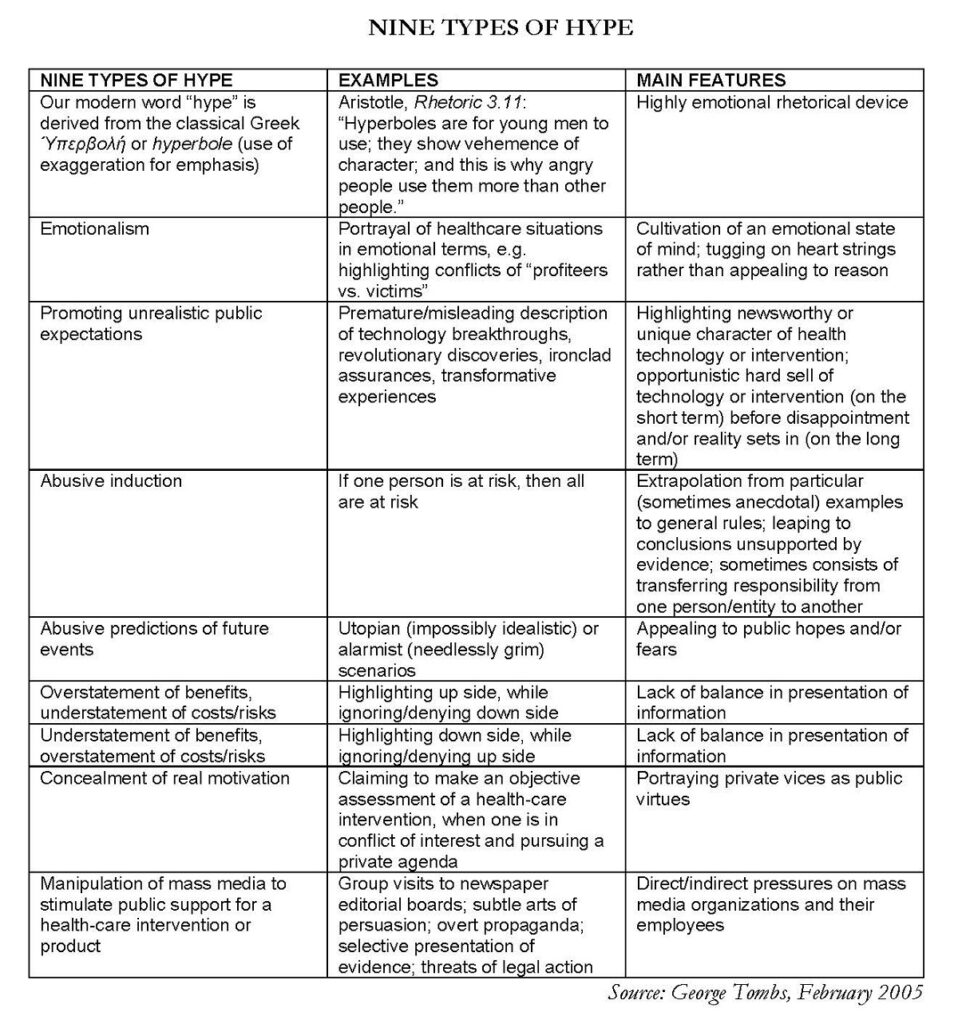

Actually, hype comes in all shapes and sizes, as the following table shows:

Some health care researchers have undertaken studies of mass media interventions in health campaigns. From the perspective of the health research community, these studies are highly regarded. But they represent the mass media essentially as distribution technologies, while understating the professional perspectives and agendas of journalists. Health care researchers need to develop a realistic understanding of journalism, in order to support the activity of journalists as potential “knowledge translators” and/or “knowledge brokers.” This involves preparing “translations” of evidence within health care and health research institutions, which lead to (a) further interpretation by trained journalists outside of these institutions, and (b) institutional writing in direct competition with mass media journalism.

Actually, the first step in producing properly-validated health information for the mass media is to recognize the large methodological and cultural differences between health care researchers and journalists.

Evidence-Based Health Care literature strikes me as being in the logico-deductive mode, whereas journalism is in the narrative mode. These are different forms of representation, with distinct ways of framing information, and of highlighting what is significant and considered valid.

Even so, EBHC and journalism share some features:

In the mass media, the leading criterion for publication is whether something is “newsworthy” or not. If the definition of newsworthy is based on shock value and an editorial judgment of what the public may wish to hear, then “hype” can be understood as a way to make things appear more “newsworthy” (emotionally compelling, revolutionary, unique, risk-free, utopian, alarming, etc.) than they are in reality.

In scientific literature, “newsworthiness” is also an important criterion. Prestigious medical journals like the New England Journal of Medicine have sometimes made premature announcements of breakthroughs, which later turned out not to be safe. This would certainly qualify as “hype.” Moreover, medical authorities sometimes make confident predictions about the “promising benefits,” “promising approach,” “exciting new possibility” and “promising strategy” of new therapies, even when the mixed results obtained from these same therapies are explicitly acknowledged.

Presenting research as newsworthy gets it into the headlines, attracts the attention of government, puts it on the public agenda. What if scientific hype is motivated by the desire of research scientists to publish unique or positive results, to stake intellectual property rights to discovery of particular diagnostics or therapies, or to position a research group for future funding?

In addition to the gap between scientific and journalism methods, and the problem of hype, evidence itself – the very core of Evidence-Based Health Care – presents enormous problems. Healthcare professionals and journalists both use evidence, but they use it in a totally different way.

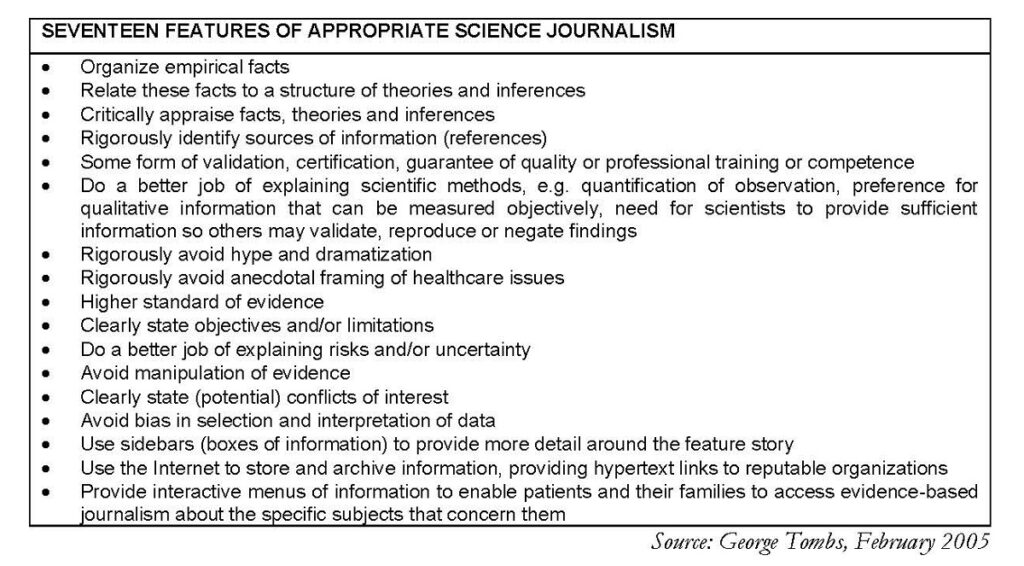

I believe an explicit model of journalism is needed, that reflects the principles of EBHC and is based on a realistic understanding of the methods and professional perspectives of journalists. This model would encourage journalists to become “knowledge translators” and/or “knowledge brokers,” while encouraging health care researchers to form a more realistic view of the possibilities and limits of the mass media and of journalism itself.

I came up with this last table (above), to chart the way towards a model for mass media, when reporting on health science.