I left London yesterday for Annecy, in Upper Savoy, where I will shortly be screening The Blinding Sea and participating in a debate at the IAE Savoie Mont Blanc, part of the Université de Savoie. There are 35 IAEs or Instituts d’administration d’entreprise in France, which are also called Écoles Universitaires de Management.

So my talk in Annecy will focus not on the physics of polar ice, as at University College London, but rather on how to develop the best business strategies based on relevant data in difficult, complex and often uncertain contexts.

One thing strikes me first of all. Business plans thrive on stability, and yet we have faced massive destabilizing shocks in recent years, from the COVID pandemic to massive environmental destruction, and Russia’s invasion of Ukraine to current chaos on financial markets. Companies have to think fast, and one key to business success during this time has been finding the right knowledge to inform business decisions. But what do we mean by knowledge?

My film contrasts two approaches to knowledge.

The Blinding Sea is about polar exploration, which may seem a far cry from the business world. Yet polar expeditions are knowledge-intensive enterprises: they require effective leadership, management of financial resources, recruitment of skilled labour, application and adaptation of technologies, co-learning, and valuing the tacit knowledge of team-members.

It is not enough for polar expeditions merely to survive: they succeed or they fail, and failure can bring death.

The two approaches to knowledge can be presented a series of questions.

- Is knowledge dynamic, open-ended, self-correcting, based on experience and practice, subject to continuous analysis/questioning, and capable of combining observations from the executive suite with the tacit knowledge from the field (employees who have valuable knowledge of processes, the market, clients)?

- Or is knowledge something finite, limited, based on tradition and authority, that is anchored in books and summed up in conversations with experts, in the relative comfort of the executive suite?

To start with knowledge as dynamic, open-ended and self-correcting. First, in joining the Belgica Antarctic expedition in 1897-1899, Roald Amundsen thought he knew something about polar exploration, and while he experimented with different tools such as skis, snowshoes, tents and sleeping-bags, he ultimately realized he had to unlearn what he thought he knew. And so he embarked on a two-year apprenticeship with Inuit in Arctic Canada, from 1903 to 1905, during which they painstakingly taught him how to dress, eat healthy food, shelter himself from extremes of cold and wind, and travel over long distances via dog team. He had to spend several years studying this knowledge in person, then translating it into his own setting, since the Inuit then had an oral culture. He combined Inuit techniques with his own Norwegian polar knowledge of skiing and glacier-trekking. Amundsen used this knowledge to great advantage during his successful South Pole expedition in 1911-1912. The Inuit taught him most of all how to work with Nature, rather than against it.

Second, Robert Falcon Scott was handpicked by Sir Clements Markham to lead the Discovery expedition of 1901-1904, despite a lack of prior polar experience. He spent a good deal of time at the library of the Royal Geographical Society, acquiring book knowledge and speaking to experts. A first major error in his planning was to uphold man-hauling as an appropriate means of transportation over long distances in the Antarctic interior. Markham pushed him to do this, on the basis that British man-haulers had successfully covered long distances in Arctic coastal regions in the 1850s. But the analogy between Arctic and Antarctic had its limits, because expedition routes reached high elevations in the interior of Antarctica, where physical demands on crew-members were far greater. Even so, Markham opposed the use of dogs and skis.

A second major error arising from the first was that Scott boiled off the nutritional value of fresh food, making it lighter for the men as they trudged along on foot, dragging their sledges behind them. Scott repeated these errors during the Terra Nova expedition of 1911-1912, and particularly during the march to the South Pole, which proved fatal to him and his last remaining crew-members. Much as we may respect Scott’s determination to “stay the course” till the very end, he died of malnutrition, starvation and hypothermia, and this can only be considered an organizational failure.

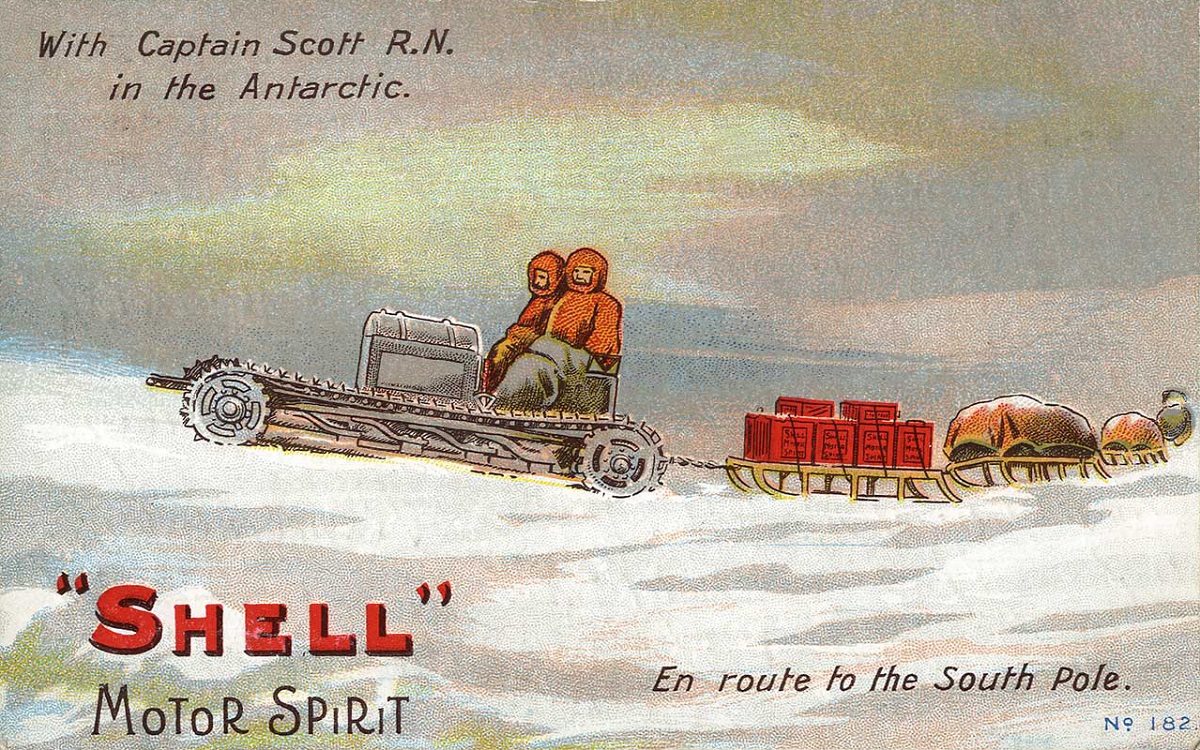

A third error lay in the Terra Nova expedition depending on experimental technologies, which had not been properly tested in real-world conditions (i.e. the motor sledges were tested in sub-zero weather in southern Scandinavia, not in Antarctica, where temperatures often dropped to -40°C).

It is clear from the historical record that Scott could have recruited Canadians and Newfoundlanders with proven polar experience, but he preferred recruiting Englishmen of the same culture and social background as himself, even when they were inexperienced gentleman adventurers. Also, he could have adopted the fur clothing of the Inuit, but opted finally for British wool, which was far less effective in extremely cold weather. He faced barriers to knowledge, including his own cultural barriers, and this was partly because his role was to affirm British leadership as a polar superpower, while showcasing British manufactured products, no matter how ill-suited they actually were to Antarctica.

I am looking forward to the event in Annecy this coming Monday. Faculty and students here are familiar with the world of snow and ice. On a good day, we can see Mont Blanc from near the town. I am sure our debate back and forth will be very stimulating.