During this film tour, my live lecture-screening at University College London takes me back, inevitably, to the most amazing dream I had, during an artistic crisis I experienced while trying to complete The Blinding Sea.

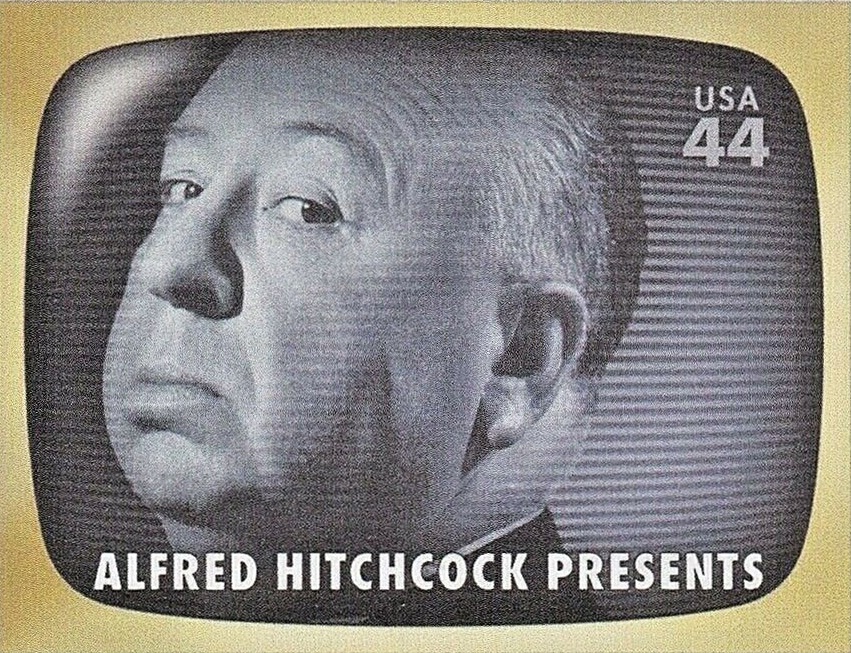

Suddenly, I had a dream. Alfred Hitchcock came to me in my dream and said: “You have elements in your film which remind you of me: Victorian iconography, dreams, Pre-Raphaelite portraits of women, haunted castles, Edgar Allen Poe, suspense, terror and vertigo, encounters with wild animals, elements from Gothic novels showing indescribably tiny people lost in grandiose landscapes, the tragic hero … Listen, I know you are unable to bring all of this together, to create a narrative unity. Your material is tremendous though. Would you accept that I take over direction of your film and pull it all together? I am good at that. Don’t worry: we can share credit as directors.”

This came as a huge surprise. I took notes as soon as I woke up in the morning!

Now, what is the connection between London, altered states and my film? Simply this. I found myself experiencing altered states as our three-masted bark raced across the Southern Ocean, in all weather. Apart from the technicalities of shooting action scenes, I noticed how different I felt to be thrusting myself into ever more demanding situations, where I risked not just my cameras, but my own life and limb as well. And this taught me to examine my main characters more closely – polar explorers who knew excitement, love, desire, fear, hatred, hunger, disgust, terror, thirst, pride and shame.

But if I could reveal elemental emotions of my own, could I not also conjure up the elemental emotions of characters in the film, by means of visuals, pacing, my tone of voice in the narration, sound effects and music?

Roald Amundsen also experienced altered states during the Belgica expedition (1897-1899), as he came to grips with how little he really knew about Antarctic exploration, and how he would have to unlearn what he thought he knew, if ever he was to succeed as an explorer in his own right.

Another person on the Belgica experienced altered states: the American medical doctor Frederick Cook, whose wildly exaggerated writings about his 1908 quest for the North Pole read like Edgar Allen Poe or Jules Verne, although Cook defended them as strictly factual … right up to the point he was publicly disgraced as a fraud. Maybe he should have written the Great American Novel instead!

I could not possibly have pulled together The Blinding Sea without following the example of Alfred Hitchcock, a Londoner and one of the greatest masters of cinema. So many of his works reveal elemental emotions, and I did my best to reveal some on my own.

On an imaginative level, after my dream, I felt as if Hitch and I were working on the film together, with Hitch coaching me. It was a demanding experience but also an enjoyable one, like an apprenticeship. I was no longer working in isolation. Dan Auiler wrote a great book called Hitchcock’s Notebooks, which quotes Hitch as saying: “The motion picture is not an arena for a display of techniques. It is, rather, a method of telling a story in which techniques, beauty, the virtuosity of the camera, everything must be sacrificed or compromised when it gets in the way of the story itself.” Hitch also says a film tells a story cinematically, through a series of images and settings and backgrounds. The way I read this is: the evidence you uncover supports the story – but a film is far more than just evidence.