Picture a two-year-old child at play. She puts on her five-year-old brother’s toy safety goggles, then crawls under a bed and pretends to be doing the breast stroke, pushing herself along at ground-level and laughing all the way.

In reading Paul Ricœur’s The Rule of Metaphor, and all the subtle introspective distinctions he makes, I realize there is a whole Western tradition of overintellectualizing that goes back to Aristotle.

At this point, in her world of make-believe, a two-year-old child speaks more directly to me about metaphors than Aristotle!

I have been thinking a lot about metaphors lately. I recently noticed a conceptual error in The Blinding Sea, and went back and fixed it. The error was to have used a metaphor-within-a-metaphor, which viewers found confusing.

In the initial version of the film, I alluded to Roald Amundsen and his intense relationship with the sea, using the dreamlike image of a red-haired woman in a skin-coloured bathing suit, swimming below the waves of a turquoise sea, as a way of illustrating that the sea was his mistress.

It took awhile for me to realize this metaphor-within-a-metaphor image was steering viewers off-course. If visual metaphors lead an audience imaginatively from one term to another, then my metaphor-within-a-metaphor was misleading the audience: they were looking at the young woman’s hair colour and slender physique and whether she was actually wearing a bathing suit at all. Whereas the point was Amundsen’s relationship with the sea, his mistress.

I therefore kept the narration and music at that point, but replaced the red-haired woman with a sequence of glittering, warm-coloured ocean waves as they build up then collapse on themselves – waves so hypnotic they practically cast a spell on you. This representation of metaphor is simpler and more to the point.

The English word metaphor comes from the ancient Greek μεταφορά, meaning “transfer” or “exchange.” Since Aristotle, and more recently Paul Ricœur, metaphors have been seen in terms of transference, analogy, resemblance, reference and substitution. To which I would add metaphors may be used as intuitive descriptions, as equations (or identities) between two terms, and as prescriptions of how things ought to be.

According to the Encyclopaedia Britannica, “The metaphor makes a qualitative leap from a reasonable, perhaps prosaic comparison, to an identification or fusion of two objects, to make one new entity partaking of the characteristics of both.”

I would like to draw out of this last paragraph the idea of crossovers, identification and fusion – three ideas that have to do with relationships between people and/or things, that have to do with imaginative movement from one term to another.

Now, you may ask: what is the possible connection between metaphors and fusions? According to one reputable online resource I found, “The world of family systems psychology identifies a dysfunctional process, called psychological fusion, which stems from insufficient self-definition by an individual and results in a dependency upon others to meet an innate need to feel accepted.” https://ieeexplore.ieee.org/document/272852

I see fusion as a process whereby a person-fusing, in a quest for self-definition, seizes on a person-to-be-fused and then treats that person not as real or tangible but rather as a symbol or metaphor, as if the role of that person-to-be-fused were somehow to complete the person-fusing, as if the person-to-be-fused were derived from the person-fusing.

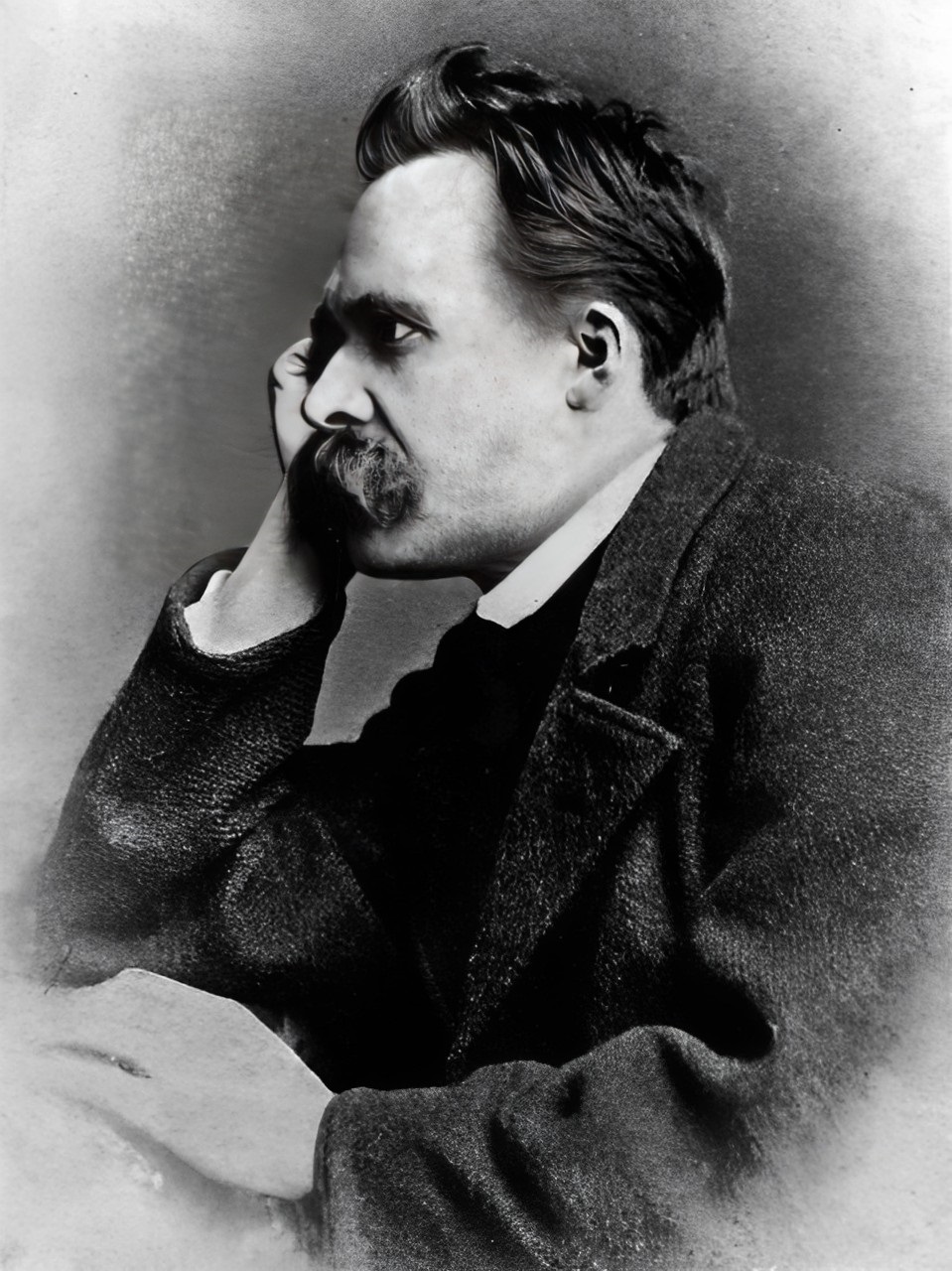

In philosophy, no better example of this process of fusion can be found than in the strange case of Friedrich Nietzsche. Here again, our Western tradition of overintellectualizing predisposes many historians of philosophy to indulge Nietzsche, to analyze his writings with subtlety, leaving aside his protofascism and misogyny, his anti-Semitism and contempt for the masses. But how can we forget Nietzsche wrote over and over again that he belonged to some exalted nobility of the mind, in a realm of atheism and naked power, well above the stupid rabble? How can we forget he held that the hallmark of the Übermensch or Superman was to act without regard for good and evil, as if his self-absorbed actions had no consequences for other people?

In casting himself as an Übermensch of the mind, Nietzsche strikes me as having been an extremely frustrated intellectual, who created an imaginative universe where he went from powerless zero to all-powerful hero, well above the rest of the population.

Nietzsche sought to refute the basis of morality, and also to better define himself, so he seized on the religious figure of Zarathustra, initiator of arguably the world’s first monotheistic religion and system of morality (in ancient Persia circa 1000-1500 BC). The Zarathustra of tradition believed in the cosmic struggle between good and evil. But Nietzsche transformed Zarathustra into someone who affirmed God was dead, and who upheld the view that the Übermensch demonstrates his superhuman capacities by rejecting the misguided and obsolete values of good and evil. This metaphorical fantasy of Zarathustra was therefore derived from Nietzsche himself.

I believe Nietzsche fused himself onto this imaginary Zarathustra, turning the Persian prophet from 1000-1500 BC into an improved version of himself, in the late nineteenth century. It didn’t matter who Zarathustra may have been in himself. As a person-to-be-fused, he was a creation of Nietzsche’s mind, that is, of the person-fusing. This was Nietzsche’s narcissistic, megalomaniac fantasy: a kind of make-believe whereby he created an exalted double of himself as secular prophet looking down on the world from the mountain-top, ignoring who Zarathustra, the person-to-be-fused, may really have been, according to Zoroastrian tradition.

I have always seen fusions as a weird misuse of metaphors, that involves transferring qualities from the person-fusing onto the person-to-be-fused, and back again the other way, equating these two people, and even defining how the person-to-be-fused ought to be.

For example, different persons-fusing, assuming (or hoping) I was the person-to-be-fused, have told me: “I am you … You are an improved version of me … I appropriate to myself what I like about you, and project onto you what I dislike about myself … I created you, and am therefore responsible for your achievements….”

I have found these various expressions of fusion disconcerting, and have rebuffed them. Actually, the person-to-be-fused is a creation of the person-fusing, in the sense that the person-to-be-fused is endowed with attributes he or she does not have in real life. The person-to-be-fused is a kind of make-believe, a psychological necessity even for the person-fusing. Which does not leave much room for the authentic self!

Over the years, I have seen people enter into fusional relationships involving both love and hate, that cause them a lot of suffering and confusion. Why? Because fusion is a two-way street, back and forth, and there is a lot of hurt, for the person-to-be-fused, to be subjected to the disorientation and transformation going on in the person-fusing’s mind.

I wonder…. In cases where two people accept to be in a fusional relationship, are they initially drawn together by some overwhelming, irresistible force? Are they unable to resist that force because they crave fusion with that other person, as a way of escaping loneliness or emptiness? Once they fuse, cleaving to one another and becoming one, it seems to me their love takes on an epic character, as if life were suddenly transformed into a thrilling passionate adventure, and they were no longer ordinary beings but had now become heroic lovers.

At first, the fusional relationship has its funny sides. Supposing the person-fusing and person-to-be-fused accept to play these roles? How can two people so different from each other suddenly begin looking, talking, walking and dressing like each other, as if one mirrored the other? Isn’t this mirroring a proof of their destiny?

As gratifying as mirroring may seem, I believe that effacing oneself just to please the other means that individual identity is now getting stifled.

Two people in a fusional relationship get used to living-for-another, maintaining the other, satisfying that other person’s aching hunger. The whole trend of their personality is to fuse with, blend into, merge into, disappear into the other, fade into the background, go unnoticed. There is never time or space to ask: “How do I see myself?” This question may even make them feel guilty.

Fusional relationships naturally seek to be total, absolute, unalloyed, unconditional. This is why they are self-defeating.

There always comes a breaking-point. The fusional relationship is blown apart with a destructive force as intense as the creative force that had initially brought it together in the first place. I have often seen people blow up one fusional relationship, then happily throw themselves into a second fusional relationship shortly after, not to mention a third … and a fourth. But I have also seen people destroyed by the break-up.

Well, Nietzsche went mad in January 1889, and never recovered. It is said his mental breakdown came when he saw a horse being whipped with great cruelty, on a street in Turin. Perhaps he was simply overwhelmed by the evil of violence, by the Zarathustra of his fantastic mind!

A person is always better off having a healthy, authentic self, and entering freely into relationships that leave space for identity … and laughter.

Like that little two-year-old girl playing make-believe, as she swims – metaphorically – underneath the bed.