Fear is “an unpleasant emotion caused by the threat of danger, pain, or harm,” according to the Oxford English Dictionary. We associate fear with suffering, distress, injury, illness and death; with deliberate trauma inflicted on us by other people; and even of being revealed to the world as we really are.

So is fear something to be avoided at all costs? Or can it play a constructive role?

At the end of the Lebanese Civil War, I remember interviewing a lady in Jounieh north of Beirut, whose son had been taken hostage by a Shi’ite militia. I was there on behalf of CBC-TV. We talked about her son’s fate. She learned he had been spirited away to Iran, and was being kept there as a slave running a shoe factory – a slave at gunpoint. She puffed her narguilé or water-pipe, then asked if I was afraid. “Yes of course,” I answered. “Good,” she said. “It’s only by feeling fear that you learn to be careful.” Ultimately it was not possible to bring her son back home safely, and he disappeared.

In recent Evidentia blogs, I have been thinking aloud about the role of fear in fairy/fantasy stories. For example, the Brothers Grimm often describe the fear of disappearing without trace, of being engulfed in the depths of Nature, of dying a miserable, cruel, forgotten death at the hands of witches.

Fear has also, for several centuries now, been associated with voluntarily exposing oneself to extreme danger, and the sublime, and the quest for absolutes in a world forsaken by God.

Overcoming fear is the driving force of many of our experiences. To overcome fear, you need first to name it, which is a way of taming it; then face it, forming an idea of the risks involved; then defy it; but you need above all to get home safely.

Fear can be a powerful motivator. According to the American test pilot Chuck Yeager: “I was always afraid of dying. Always. It was my fear that made me learn everything I could about my airplane and my emergency equipment, and kept me flying respectful of my machine and always alert in the cockpit.”

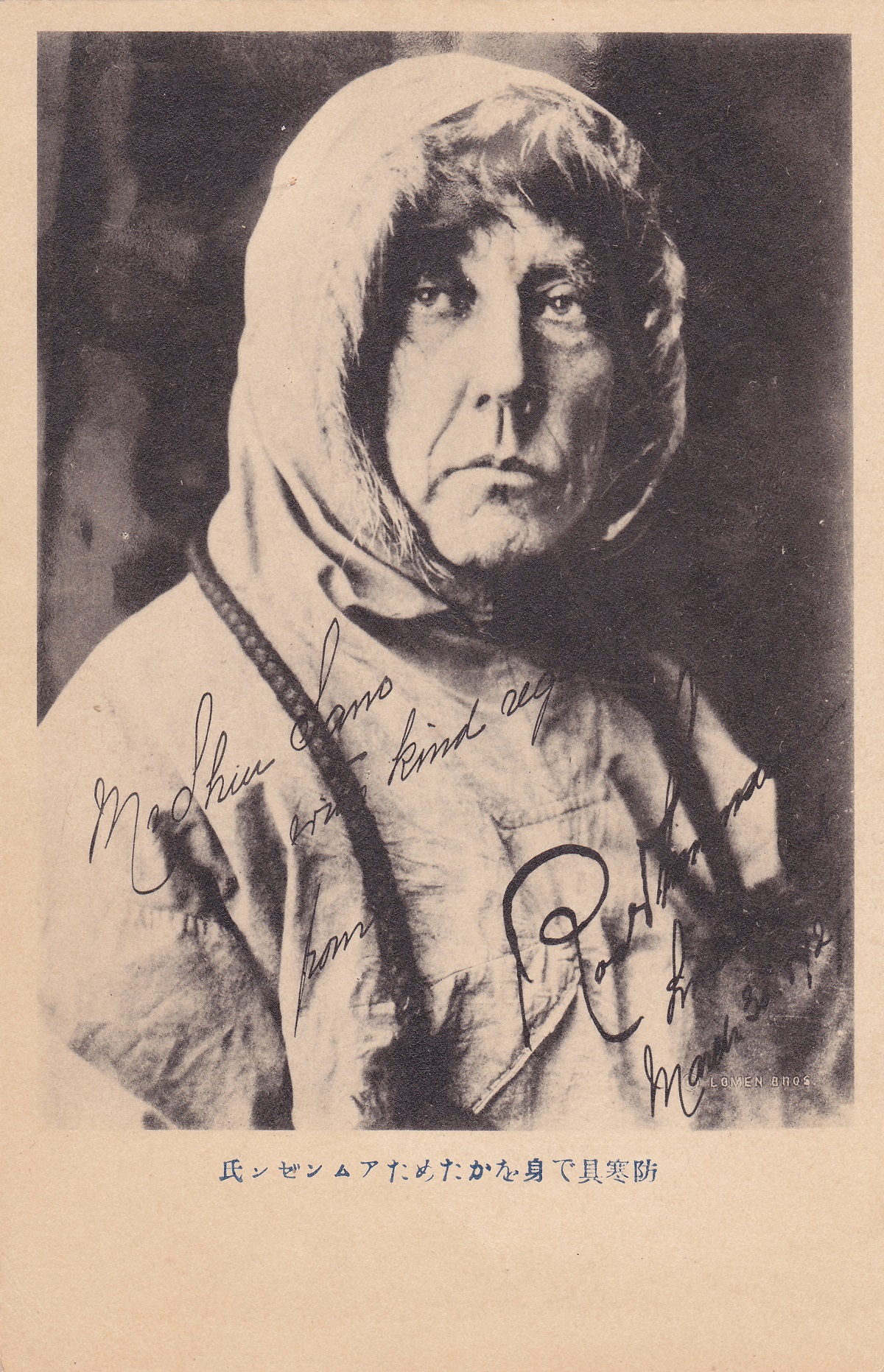

I am close to completing the feature film The Blinding Sea, a documentary dealing with polar exploration a century and a more ago, with a particular focus on the Norwegian explorer Roald Amundsen. In the course of making the film, I have shot footage of people and animals interacting in awe-inspiring landscapes in the Arctic and Antarctic. At one point, the windchill when I was filming got down to -68.3° C (or -91° F). No wonder my camera (and my fingers) froze. I am using visuals that fall under the genre of the polar sublime.

The polar regions sometimes remind me of the Sahara desert, as in the photograph at the top of this blog, which I took near Zagora, Morocco. Cold and hot deserts have that same quality of emptiness. Your lay yourself bare, and you come up so close to nothingness that it envelopes you.

My life experience, fairy/fantasy stories and the film have got me thinking about the difference between the sublime and the beautiful.

This was a subject of interest to 18th century philosophers.

For example, in 1757, the British philosopher Edmund Burke wrote A Philosophical Enquiry into the Origin of our Ideas of the Sublime and Beautiful. In this work, he states: “Whatever is fitted in any sort to excite the ideas of pain and danger, that is to say, whatever is in any sort terrible, or is conversant about terrible objects, or operates in a manner analogous to terror, is a source of the sublime; that is, it is productive of the strongest emotion which the mind is capable of feeling. I say the strongest emotion, because I am satisfied the ideas of pain are much more powerful than those which enter on the part of pleasure.”

And a little later on in the same work, Burke states: “No passion so effectually robs the mind of all its powers of acting and reasoning as fear. For fear being an apprehension of pain or death, it operates in a manner that resembles actual pain. Whatever therefore is terrible, with regard to sight, is sublime too, whether this cause of terror be endued with greatness of dimensions or not; for it is impossible to look on anything as trifling, or contemptible, that may be dangerous. There are many animals, who, though far from being large, are yet capable of raising ideas of the sublime, because they are considered as objects of terror. As serpents and poisonous animals of almost all kinds. And to things of great dimensions, if we annex an adventitious idea of terror, they become without comparison greater. A level plain of a vast extent on land, is certainly no mean idea; the prospect of such a plain may be as extensive as a prospect of the ocean; but can it ever fill the mind with anything so great as the ocean itself? This is owing to several causes; but it is owing to none more than this, that the ocean is an object of no small terror. Indeed terror is in all cases whatsoever, either more openly or latently, the ruling principle of the sublime.”

Burke notes that the beautiful, on the other hand, operates at quite a different emotional level: “We shall have a strong desire for a woman of no remarkable beauty; whilst the greatest beauty in men, or in other animals, though it causes love, yet excites nothing at all of desire. Which shows that beauty, and the passion caused by beauty, which I call love, is different from desire, though desire may sometimes operate along with it; but it is to this latter that we must attribute those violent and tempestuous passions, and the consequent emotions of the body which attend what is called love in some of its ordinary acceptations, and not to the effects of beauty merely as it is such.”

The German philosopher Immanuel Kant wrote Observations on the Feeling of the Beautiful and Sublime in 1764:

“The sublime moves, the beautiful charms. The mien of a man who is undergoing the full feeling of the sublime is earnest, sometimes rigid and astonished. On the other hand the lively sensation of the beautiful proclaims itself through shining cheerfulness in the eyes, through smiling features, and often through audible mirth. The sublime is in turn of different kinds. Its feeling is sometimes accompanied with a certain dread, or melancholy; in some cases merely with quiet wonder; and in still others with a beauty completely pervading a sublime plan. The first I shall call the terrifying sublime, the second the noble, and the third the splendid. Deep loneliness is sublime, but in a way that stirs terror. Hence great far-reaching solitudes, like the colossal Komul Desert in Tartary, have always given us occasion for peopling them with fearsome spirits, goblins, and ghouls. The sublime must always be great; the beautiful can also be small.” (The “Komul Desert” mentioned by Kant seems to be the modern-day Taklamakan Desert of northwest China.)

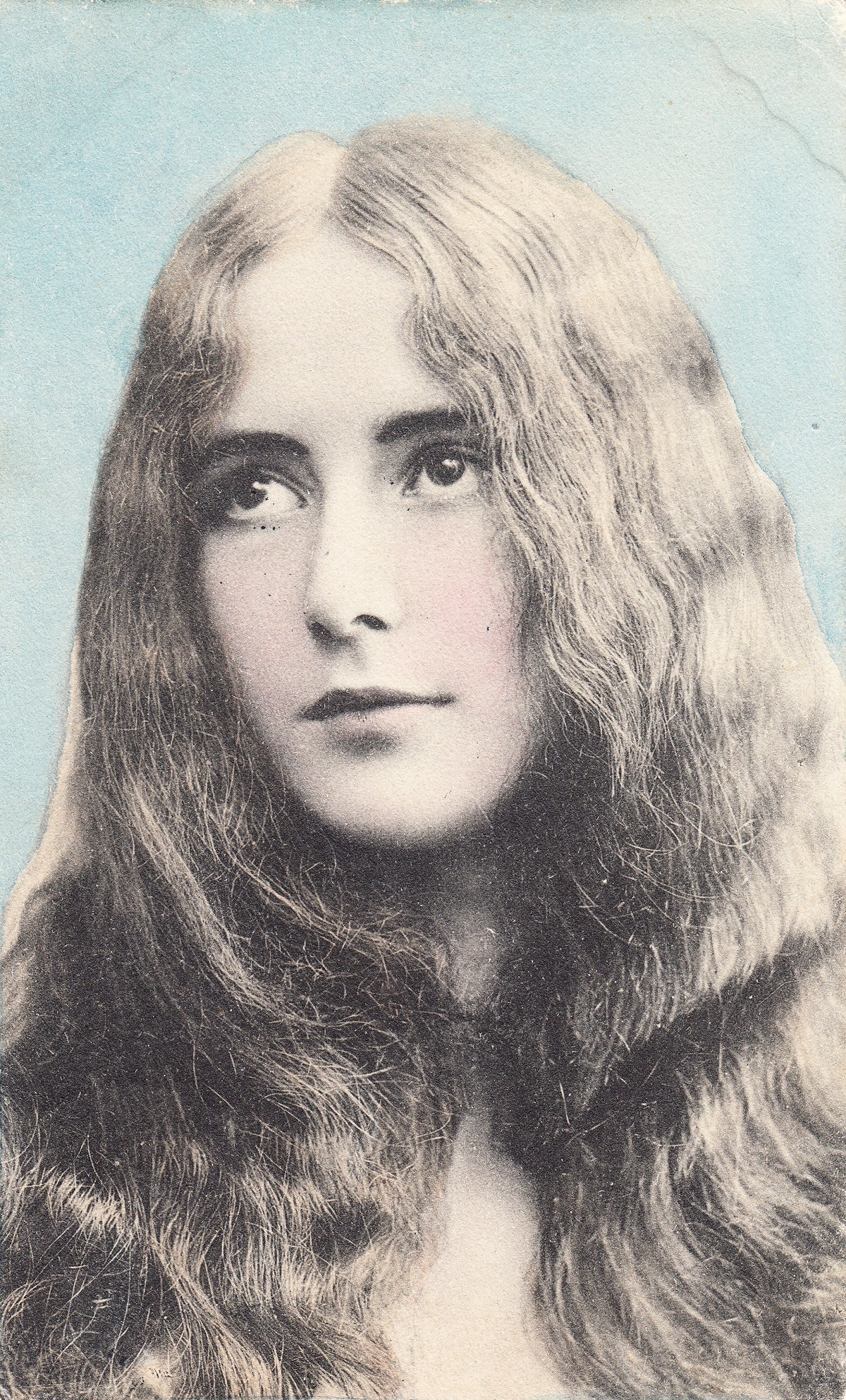

If Kant is right, then polar and Saharan landscapes move us because they are sublime, whereas Cléo de Merode charms us because she is beautiful.

Is there any psychological or esthetic reason for this fascination with the sublime?

John T. Goldthwait, the translator into English of Kant’s book, writes in his introduction: “Kant looks at his subject matter under the aspect of the four accepted classifications of the temperaments of men – melancholy, sanguine, choleric, and phlegmatic. He does not claim that the body humors actually cause the different temperaments, merely that there are noticeable types and that the inner feelings correlate with the other characteristics of each type. The melancholy man has a greater proportion of the sublime in his make-up; the sanguine, of the beautiful; the choleric, of the gloss or appearance rather than of the substance of sublimity; and the phlegmatic, neither factor to any discernible extent. Very importantly, the interplay of the sublime and the beautiful generates a description of our moral lives, accounting for the various human motivations including the motivation of moral principle.”

So, I wonder. If Goldthwait and Kant are right, then fascination with the sublime, the terrorizing and the dreadful may be a melancholy sort of obsession. But then, I am not a melancholy person. I believe the fascination with the sublime is sometimes part of a quest for absolutes, in a world forsaken by God. You voluntarily expose yourself to extreme dangers, and experience the thrilling adrenaline rush of facing the vast expanse of the wilderness. You realize you are utterly vulnerable and insignificant against the backdrop of hurricanes at sea and looming glaciers and jagged mountain ranges; you step right up to the very edge of nothingness; but then, hopefully, you stand back from fear, and return home to your normal occupations.

This is what gives such extraordinary power to Robert Falcon Scott’s evocations of Nature in the books he wrote about the Discovery and Terra Nova expeditions to the Antarctic: they are sublime, even to the point of being heroic. Scott was by all accounts a melancholy person. Amundsen’s writing is nowhere near as moving, so he may have been less fascinated by the sublime, and more of a practical person.

Fear is to be found in many kinds of story-telling. Journeys through fear are one of the great themes of art, from Orpheus to Dante, and war reporting to exploration narratives.

It is often said that Roald Amundsen and other explorers of his day got the “polar bug.” I have come to believe they felt compelled to return over and again to the polar regions, so they could defy death and melt into the pure whiteness, the utter stillness of the frozen land and sea. They were irresistibly drawn back to the polar theatre, so they could feel the thrill of fear, and use that fear as a springboard to achievement. Getting home safely may have been a secondary concern.