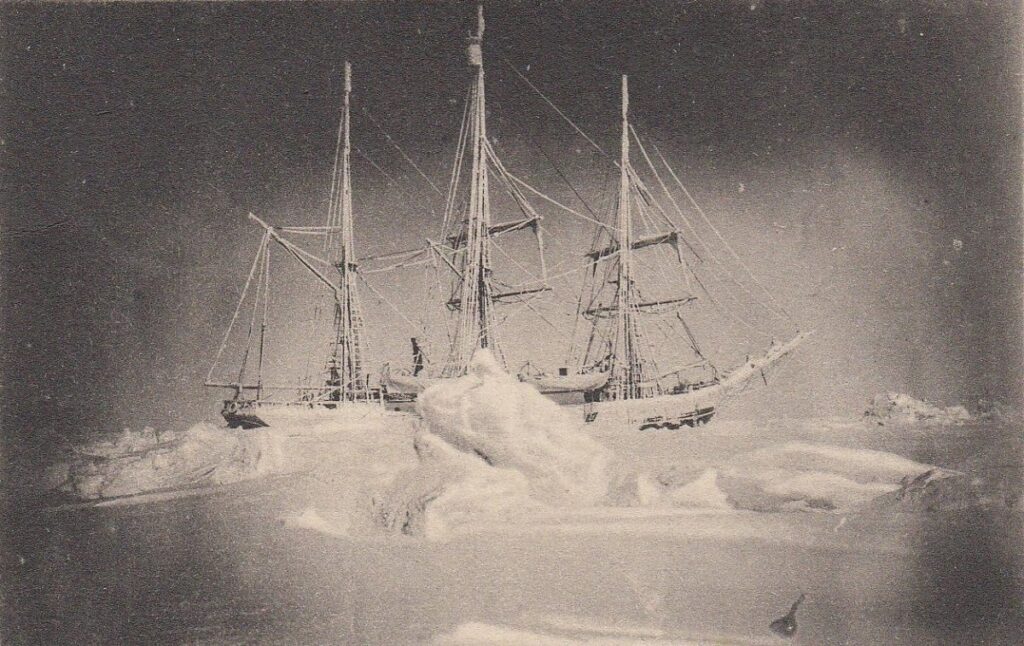

As a medical doctor from Brooklyn, Frederick Cook saved the Belgica officers and crew in 1898-99, by treating their scurvy with fresh meat, experimenting with light therapy as a remedy for depression and paranoid delusions, then urging expedition commander Adrien de Gerlache to hack the ship out of the ice-pack with axes and saws.

A talented photographer and painter, his images of the Belgica at night still strike us as remarkable today.

Cook had a genuine interest in the Greenland Inuit, and convinced Roald Amundsen during the Belgica expedition to learn first-hand from the tremendous knowledge system of the Inuit in Nunavut.

But it was not enough to be interested in Aboriginal people. Cook had to prove he knew more about Aboriginals than anyone else. During a brief layover of the Belgica at Harberton, Tierra del Fuego, he laid his hands on an unpublished Yahgan-English dictionary compiled by British missionary Thomas Bridges in Tierra del Fuego. Cook later tried to publish the dictionary under his own name, as if he could possibly have mastered 30,000 words of Yahgan during the three short weeks he spent ashore there, whereas he had only minimal contact with Yahgan Indians and couldn’t understand a word they were saying.

There was an infantile or ingenuous side to Cook, running parallel to his grandiosity: he fantasized about total success in childlike fairytale terms, which sounds to me like arrested development, unless it was a bizarre but conscious attempt to forestall criticism. I would call this “fairytale narcissism.” Strangely it ran alongside Cook’s obvious clear-cut accomplishments and abilities. Another possibility is that over time Cook developed a kind of Munchhausen syndrome.

He was a promising author, like a cross between Edgar Allan Poe and Jules Verne, with a special gift for Gothic purple. But his words, like a spinning whirlwind of impressions, delusions and fantasy, make me wonder why he needed to exaggerate, to dwell on altered states. Was he trying to shift the attention of readers to something he could control? It is true that these purple passages also contain medical observations:

For example, in describing the onset of the months-long Antarctic night: “The darkness grows daily a little deeper, and the night soaks hourly a little more colour from our blood. Our gait is now careless, the step non-elastic, the foothold uncertain. The hair grows quickly, like plants in a hot-house, but there is a great change in the colour. Most of us in the cabin have grown decidedly gray within two months, though few are over thirty. Our faces are drawn, and there is an absence of jest and cheer and hope in our make-up which, in itself, is one of the saddest incidents in our existence. There is no one willing to openly confess the force of the night upon himself, but the novelty of life has been worn out and the cold, dark outside world is incapable of introducing anything new. The moonlight comes and goes alike, during the hours of midday as at midnight. The stars glisten over the gloomy snows. We miss the usual poetry and adventure of home winter nights. We miss the flushed maidens, the jingling bells, the spirited horses, the inns, the crackling blaze of the country fire. We miss much of life which makes it worth the trouble of existence.”

Or again, in Cook’s My Attainment of the Pole: “Shortly after black midnight descended I began to experience a curious psychological phenomenon. The stupor of the days of travel wore away, and I began to see myself as in a mirror. I can explain this no better. It is said that a man falling from a great height usually has a picture of his life flashed through his brain in the short period of descent. I saw a similar cycle of events. The panorama began with incidents of childhood, and it seems curious now with what infinite detail I saw people whom I had long forgotten, and went through the most trivial experiences. In successive stages every phase of life appeared and was minutely examined; every hidden recess of gray matter was opened to interpret the biographies of self-analysis. The hopes of my childhood and the discouragements of my youth filled me with emotion; feelings of pleasure and sadness came as each little thought picture took definite shape; it seemed hardly possible that so many things, potent for good and bad, could have been done in so few years. I saw myself, not as a voluntary being, but rather as a resistless atom, predestined in its course, being carried on by an inexorable fate.”

I wonder whether this colourful language about polar desolation and inner turmoil was a form of mystification, a manipulative literary strategy intended to charm and deceive readers?

Frederick Cook had the gift of the gab, and sometimes the gab got the better of him. An aspiring mountaineer, he claimed to have reached the summit of Mount McKinley in 1906, and was later proven to have done no such thing.

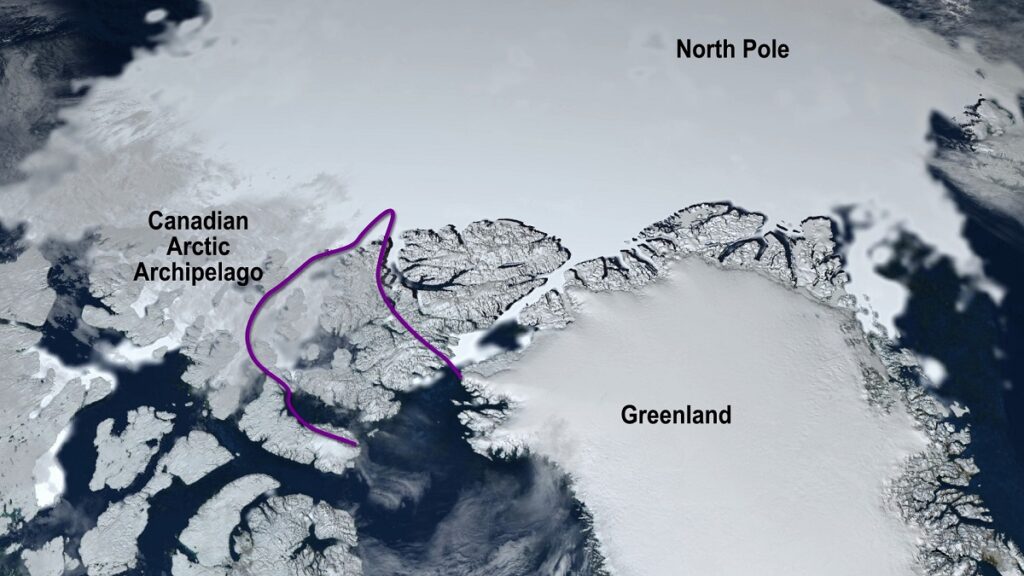

Cook is mostly remembered for his discredited claim to have reached the North Pole with two Greenland Inuit in April 1908. This immediately renewed his conflict with fellow American explorer Robert Peary, who presented a rival claim to discovery of the North Pole in April 1909. (They had already fallen out in the 1890s while exploring Greenland.) Peary had strong allies in the US Navy and the Congress, and this helped him send Cook running for cover. Actually, as Wally Herbert shows convincingly in Noose of Laurels: Peary, Cook, and the Race to the North Pole, neither Cook nor Peary could have made it to the North Pole. Whatever evidence they produced simply does not stand up to critical scrutiny.

I note that some Cook defenders resort to conspiracy theories to explain away all his deceptions not to mention self-deceptions. I have seen enough of criminal trials to know this is a common defence strategy. It also suggests to me that Cook’s defenders lack the evidence to present a solid case.

Once his exploring was done, Cook became a stock promoter in the oil business. He was convicted on fourteen counts of fraud and served seven years at Leavenworth Prison in Kansas, from 1923 to 1930. He received a presidential pardon shortly before dying. His old friend Roald Amundsen enraged Peary and the Washington establishment, for visiting Cook behind bars. But Amundsen was acting as a friend whose life Cook had once saved, not as a judge.

Was Frederick Cook a conjurer, an illusionist, a manipulator keeping his eye on the next hoax coming along? Was he a fairytale narcissist, unaware of his self-deceptions? I wrote a recent blog about Janus, the Roman god facing in two directions at the same time. All of us have our contradictions. But I have rarely come across a brilliant historical figure who was, at the same time, driven over and over again to sabotage himself.