Jean Potocki was a strange figure. A bundle of contradictions from the late 18th/early 19th century, he was a wandering scholar, a scientist after a fashion, and a remarkable novelist.

A count from one of Poland’s most powerful families, he was fluent in French yet barely capable of speaking Polish; he lived off the income from his estate and 5000 serfs at Uładówka (in what is now west-central Ukraine) while advocating greater liberties; he upheld Polish nationhood up till the final partition of 1795, then became staunchly pro-Russian to the point of drafting strategies for imperial Russia’s expansion across southern and eastern Asia; he pursued a programme of rational research while filling his fiction with ghosts, demons, corpses, debauched sirens, vampires, bandits, hooded inquisitors and scenes of shuddering frenzy in underground pleasure palaces, stables, wayside inns, torture chambers, as well as beneath gallows, on battlefields, and during long rambles on horseback.

On reading François Rosset and Dominique Triaire’s remarkable biography of Potocki (published by Flammarion in 2004), I have come to realize there was a peculiar kind of logic in Jean Potocki’s life (which ended in suicide).

The Polish aristocracy formed a caste in society, and like castes everywhere was self-referential although not self-sufficient. Europe was then a strategic chessboard, with invading armies sweeping east and west across it. The Polish aristocracy in occupied territory had to strategize in order to hold onto the source of its power and rank – forming alliances with other like-minded aristocratic families from the same caste, and holding onto vast landed estates (the seat of palaces, castles, manors etc.). This was after all, the era of Polish partitions, between 1772 and 1795, during which Russia, Prussia and Austria gobbled up the Polish-Lithuanian Commonwealth, depriving Poland of independent nationhood. After which came the Napoleonic Wars and yet more uncertainty….

Some aristocrats, like Jean Potocki, periodically switched sides, finding new masters to serve.

Potocki’s French writings range over many subjects, from the ancient origins of the Slavic peoples to travels in Morocco, Egypt, Turkey and Chechnya, and from political pamphlets to plays. But the most interesting of his works is without doubt Manuscrit trouvé à Saragosse (The Manuscript Found in Saragossa, in the Penguin Classics translation by Ian Maclean).

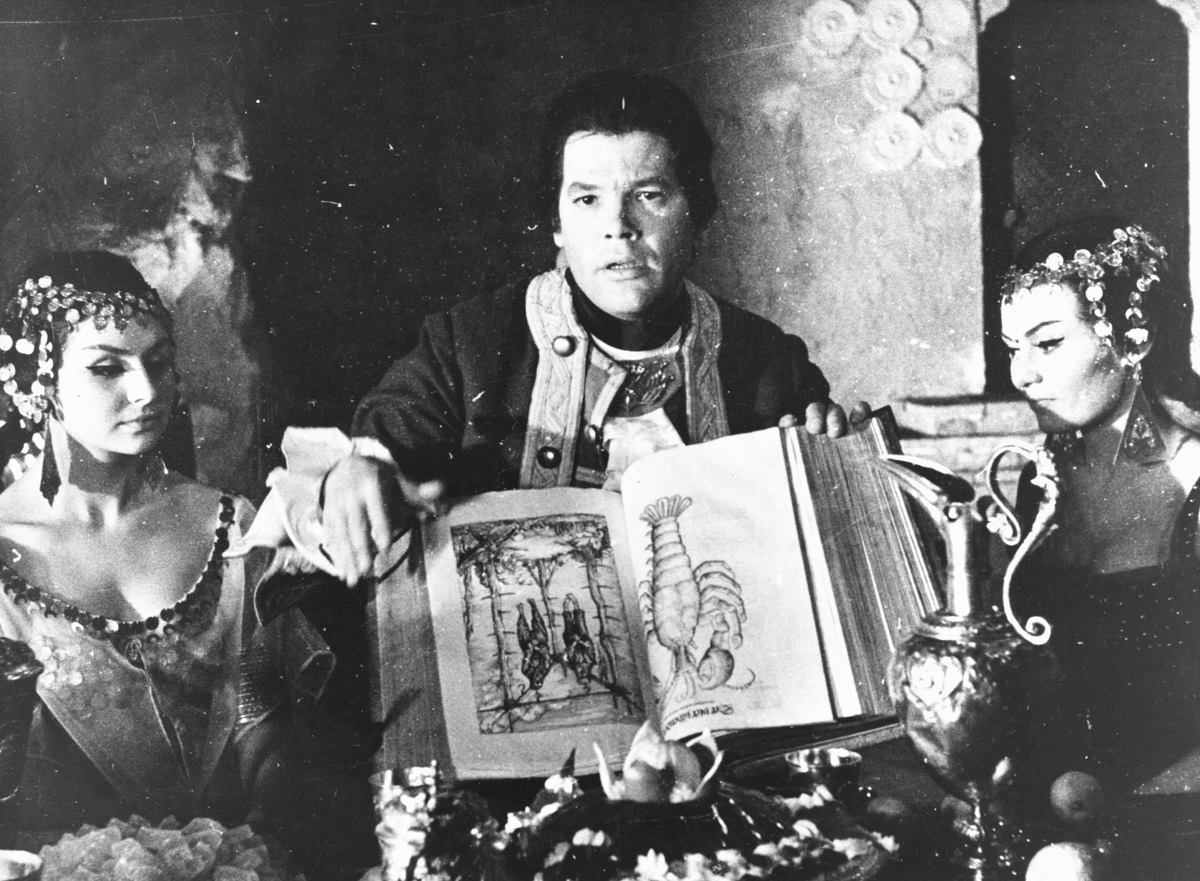

I am not going to retell tales already told and retold by Potocki, but I will mention a few aspects of the novel and of the film Rękopis znaleziony w Saragossie directed by Wojciech Has in 1965.

The Manuscript tells the story of Alphonse van Worden, who chances across a leather-bound esoteric volume during a battle in Spain. He believes the manuscript holds the key to his destiny. By turns picaresque and occult, this frame-tale novel containing stories within stories, spread over sixty-six days, sees van Worden drawn into a troubling but gratifying relationship with two Tunisian princesses (and also sisters), Emina and Zubeida. He often finds himself sharing nights of passion with them both. These sexual encounters are implied rather than described explicitly.

The narrative is full of shimmering, trembling imagery, and characters changing identities before our eyes. The theme of a man enjoying the sexual favours of two women at the same time is repeated throughout the novel (e.g. with Camilla and Inesilla, then the gypsy chief’s two unnamed daughters, then Antonia and Marita, then Quita and Zita, and finally the Duchess of Avila and her purported sister Leonor, who is really the duchess herself, in disguise).

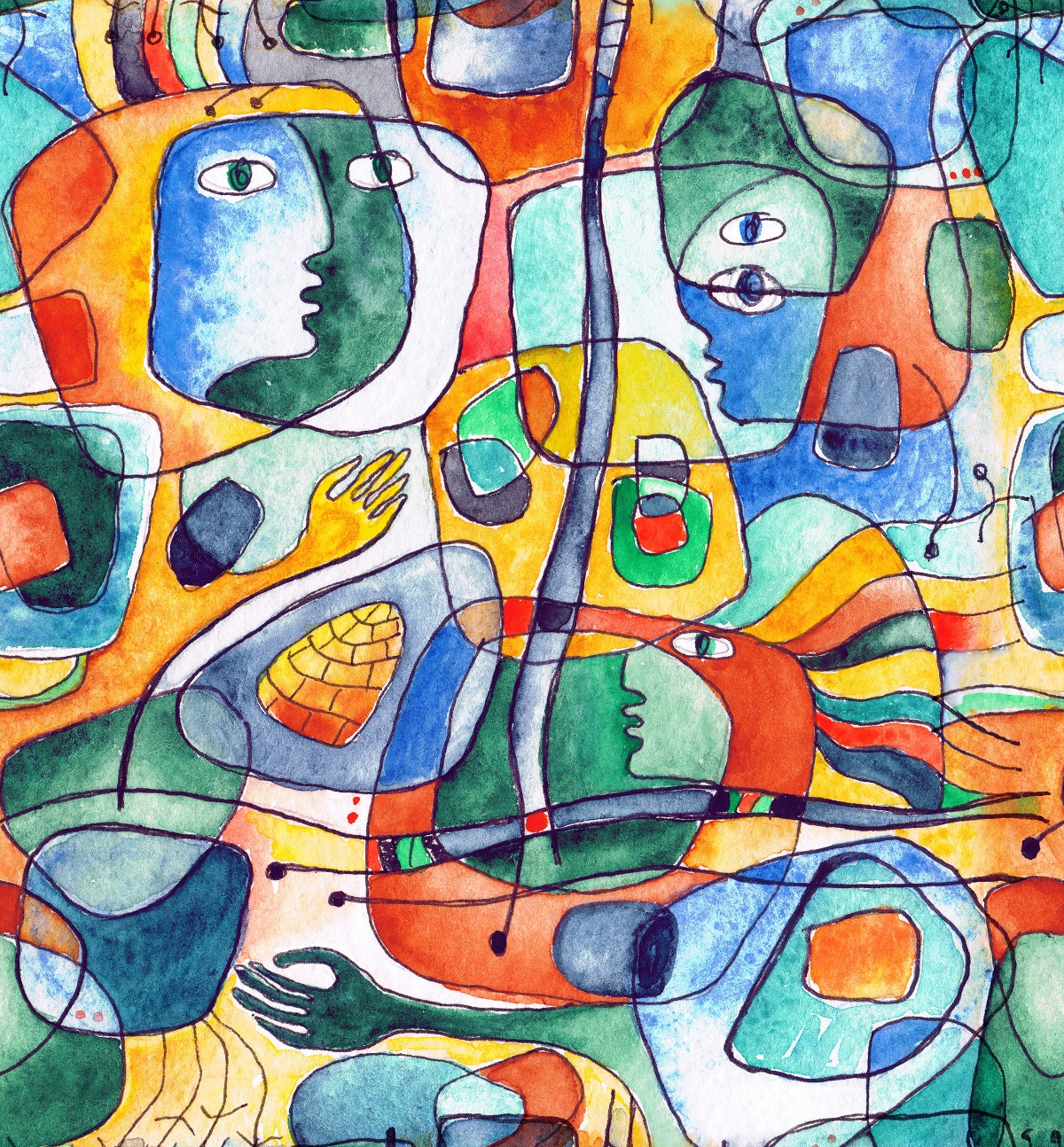

Each story is told by a different character, but it eventually becomes clear that the stories are often one and the same, and are being retold from a new perspective, like characters facing every which way in a Cubist painting. This is one of the most striking features of the Manuscript.

The main character van Worden, like Potocki, is a wandering scholar. He is on an existential quest, knows moments of angst not to mention sheer horror, is drawn constantly into new situations, and understands nothing. The novel is located in a kind of dreamland between Judaism, Catholicism, Islam and pagan culture, flipping from one tradition to the next as the characters deceive, seduce, betray and occasionally get to know one another.

Perhaps the most interesting feature of the Manuscript is the way reality is contrasted with ghostly apparitions, delusions, paranoid frenzy – the way ineffectual self-defeating noblemen remain loyal to lost causes (like honour), yet along the way discover their own shifting loyalties and (incestuous) family secrets. It is a novel of ambiguity, of ambivalence, of shattered identities.

Two big differences between the novel and the film by Wojciech Has are the portrayal of character:

In the novel, Don Roque Busqueros is a dark, scheming figure. But in the film, he becomes a comical rogue and intriguer – almost a stock character.

And in the novel, Doña Rebecca Uzeda is a fair-haired Jewish cabbalist with a mind of her own and the courage to look into mirrors and penetrate new dimensions of spiritual reality. But in the film she becomes an ever-smiling, discreetly sensuous, entrancingly voluptuous beauty, as if she were a Polish noblewoman of the late 18th/early 19th century. In fact, the role of Beatrice is played in the film by Beata Tyszkiewicz, a countess.

Zbigniew Cybulski, the actor playing Alphonse van Worden, met with a fate worthy of Jean Potocki: while playing a daring game of jumping on and off trains in motion, he slipped between the wheels of his train in 1967, and was crushed to death.