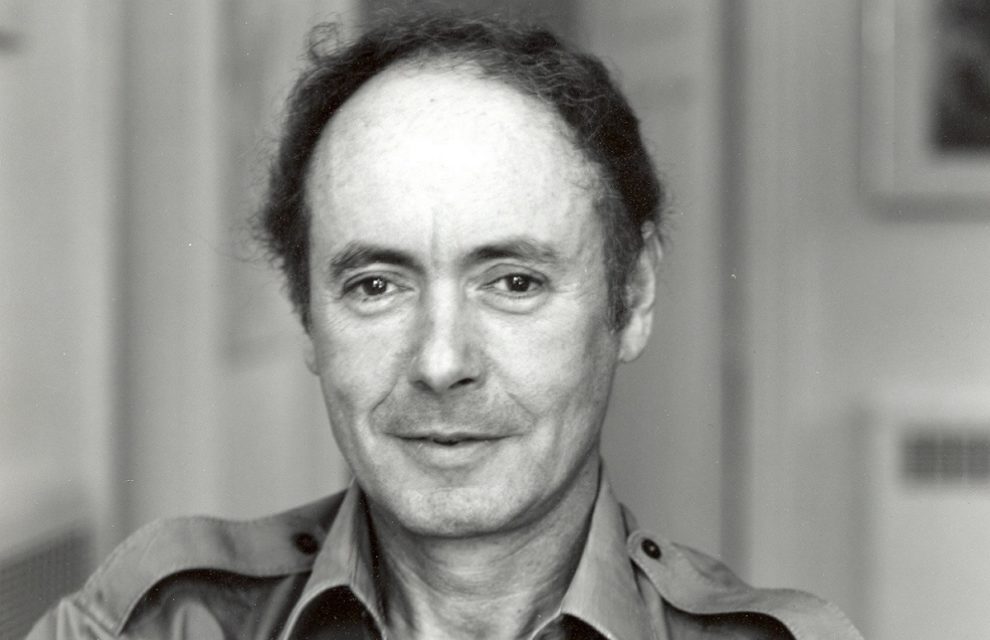

I was fortunate to know Valentine Boss, a History professor at McGill University, for many years.

As an undergraduate, I took his courses on the History of Russia, and the History of Science. It wasn’t so much the subject matter that interested me as the way he taught it: here was a rigorous historian, someone with a beautiful, effervescent command of language and a phenomenal memory, a man who had started his career in Canada in the theatre and therefore had the mind of an artistic creator.

https://archive.macleans.ca/article/1956/12/22/a-moving-new-portrayal-of-the-nativity-story

He also had experience of the world, including personal trauma during Stalin’s purges, when he and his mother were lucky enough to flee Moscow for Murmansk and then take a convoy to Scotland, in January 1942. His father was assassinated on Stalin’s orders. This event fell like a shadow over his life, although his happy relationship with his mother mirrored my relationship with my own mother.

History was a domain of knowledge without borders. Any conversation with Prof. Boss was like a voyage of discovery in the realms of art, literature, philosophy, science, religion and languages. I can’t say this was due to his degrees at Cambridge or Harvard. He took a personal interest in … well, everything … and had a rare ability to make connections, bringing things together in a brilliant synthesis. I think Cambridge and Harvard were lucky to have him as a student.

And his approach in the classroom and seminars was Socratic. It was never about him – it was always about the students, whom he would guide along, one question at a time, as they put together their own answers. Even so, I remember now – and it just makes me cringe – that he did occasionally take the mickey out of the more rambunctious or arrogant students, by putting them on the spot in class, asking them tough questions about abstruse concepts. I managed to avoid eye-contact with him, at moments like that….

When it was time for me to do a Master’s degree in the History and Philosophy of Science, I naturally chose Prof. Boss as thesis advisor. By this time, I was very gradually beginning to call him “Valentine.” He understood that I was a mature student with a full-time job and a full-time family. He gave me a lot of latitude. And I worked hard on my thesis, although he noted with a twinkle in his eye that I had only plowed through hundreds of books, whereas I cited no scholarly articles. (In fact, I had a hard time understanding how to access scholarly articles on JSTOR!)

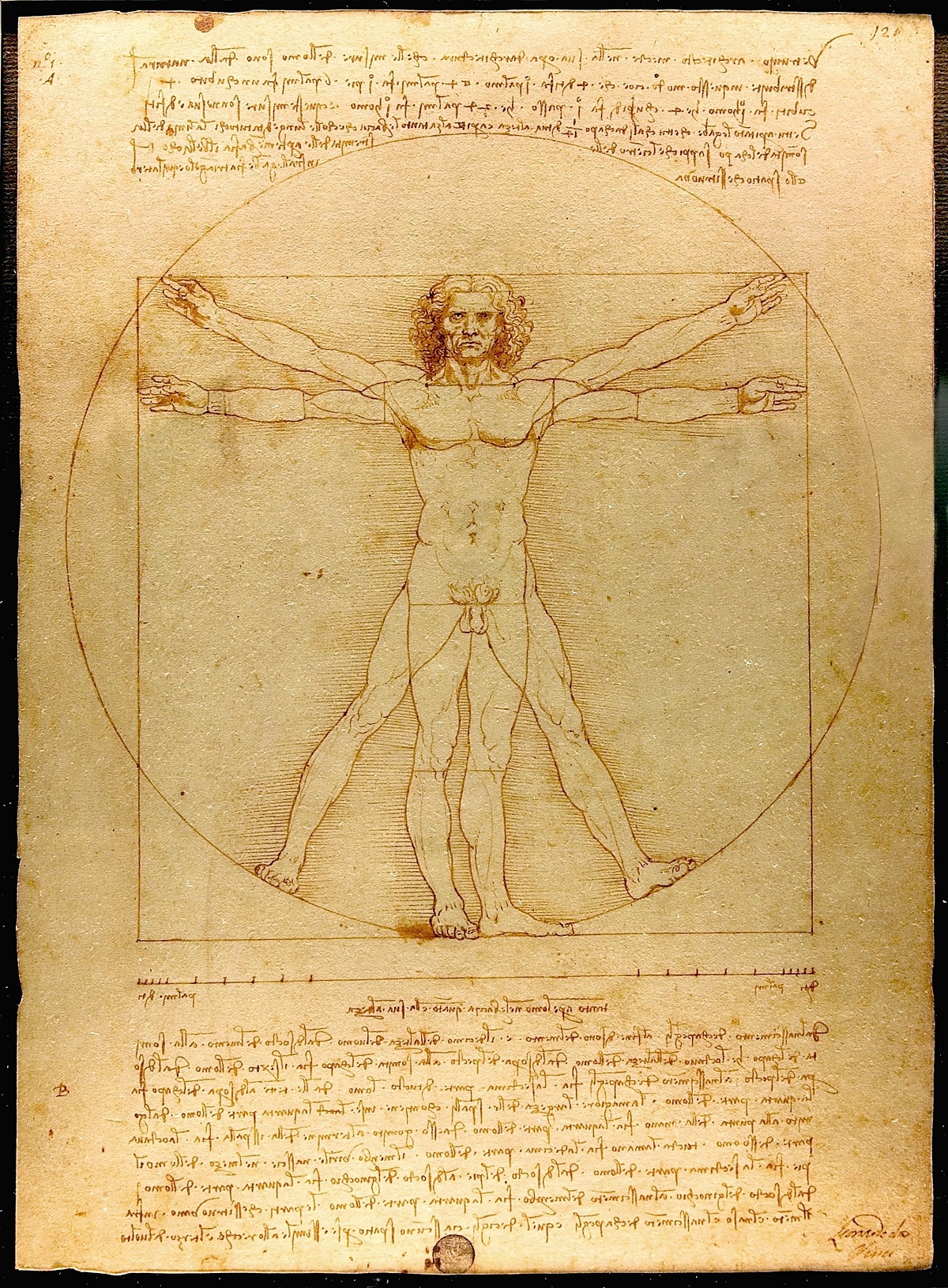

The subject of my thesis was one of the main transitions of modern times, from essentially a faith-based culture to more of a secularized knowledge-based culture. Valentine knew all about prophecy, spiritual magic and demonic magic, through his work on John Milton and Sir Isaac Newton. He understood that a historian of science needed to know the Bible, and the way it was interpreted at various times. He acknowledged that many of the leading lights of the early modern scientific revolution – Paracelsus, John Napier and Isaac Newton – were also men of their time, with a view of the world rooted in religious and hermetic beliefs which we would categorize nowadays as superstitious.

European culture was so saturated with a religious mindset that many of its features survived into the emerging scientific mindset. The transition (or paradigm shift) was gradual. According to the new way of thinking, it was no longer credible that God or Satan caused hurricanes, comets, pestilence, war, famine, disasters and mass deaths. For some, this was a traumatic transition. It made people anxious to realize humans were not God’s chosen species living in a closed world created in 4004 BC: we were just one of many species living on a pale blue dot in an infinite universe. And of course this realization was dangerous, given all the pressures the Church brought to bear on free-thinkers.

Valentine was comfortable with my thematic approach, which owed more to French history-writing than to the facts, dates and great men of conventional history-writing. Indeed, la nouvelle histoire has to do with cultural history, the history of representations and the history of mentalities. Art as a form of representation plays a vital part in our understanding of the world.

He saw it as perfectly normal that I should explore Lucretius, the Bible, St. Augustine and Leonardo da Vinci as much as Sir Francis Bacon, Galileo Galilei, René Descartes and Blaise Pascal, in seeking to explain the transition from a faith-based culture in a closed world to a knowledge-based culture in an infinite universe.

He accompanied me during the Master’s degree, and subsequently my Doctorate, as I made a transition of my own. I now saw spirituality as a strictly private matter, a dimension to be lived rather than talked about. And I saw the work of the historian as examining all the connections running through culture, from the myths and metaphors of art to the ever-expanding world of scientific knowledge.

Anyway, along with Valentine, I explored different formulations of the scientific method from the Renaissance onwards, and attempts either to harmonize science with religion, or to avoid harmonizing them altogether. For example, Bacon insisted it was wrong to wish to harmonize religion and science in every respect, since natural philosophy would end up teaching us about God’s power in any case. Galileo claimed that an empirically demonstrated scientific hypothesis was literally true. Descartes suspended belief (including religious belief) until rigorous self-questioning, based on carefully laid-out rules of rationality, could establish its validity. Pascal tightly circumscribed reason itself, thus removing religion from the purview of reason altogether. By the 19th century, some advocates like Auguste Comte and Ernest Renan sought to transform science into a new religion, which was like indulging in the either/or worldview.

Valentine offered many insights, many suggestions of avenues to pursue and sources to read. By the time I completed my doctorate, we had become friends. He joined in some of our family fun over the years – parties, concerts, book launches. My eldest daughter took his History of Science course at McGill. Valentine occasionally invited me to give guest lectures on things I was doing. I certainly modelled my own teaching, as a university professor, on what I had experienced with him.

I am very grateful that his wife Militsa Krivokapich should invite me over for frequent visits, during his declining years. I was surprised how lucid he was, even with prostate cancer and Parkinson’s Disease. We spoke about all the subjects that interested us – that is, history, art, literature, philosophy, science, religion and languages. We also spoke about the future of education. He told me – as he had never told me before – about his mother and the work she had done as costume-designer on films like The Red Shoes and The Tales of Hoffmann. He forgave me for never quite managing to explain Gottfried Wilhelm Leibniz and his theory of monads!

And in those visits, we laughed about life. In fact, Valentine and I laughed most of our way through my undergraduate years, my Master’s and my Doctorate. That is how I remember him, now that he is gone.

Thanks to Militsa Krivokapich for the photo at the top of this blog, taken by David Miller.