I am reminded, in reading Maurice Merleau-Ponty, Paul Ricoeur and Charles Taylor recently, of what I would call “the composite approach to scholarship.” This consists in identifying snippets from notable thinkers, taking them out of context, and then painstakingly piecing them together to form patterns, building up a picture, highlighting contrasts, and giving the whole work a fresh narrative unity.

In fact the composite approach to scholarship becomes like a virtuoso performance, where an author like Taylor quotes in a short work from a wide range of thinkers over a 2400-year stretch of time – Plato, Aristotle, Saint Augustine, Descartes, Locke, Spinoza, Tocqueville, Nietzsche, Foucault and Derrida.

Reading Taylor is something like embarking on a journey through the history of philosophy – a journey in which we are tourists led along by Taylor, and we have tantalizingly short glimpses of what has been built on the shoulders of giants, although this journey ultimately leads us back to Taylor himself, to his intentions.

Now you may say that Merleau-Ponty, Ricoeur and Taylor are philosophers, not historians, so why worry? Surely, with so many philosophers taking the composite approach to scholarship, isn’t it an acceptable form of discourse? Is there some better way?

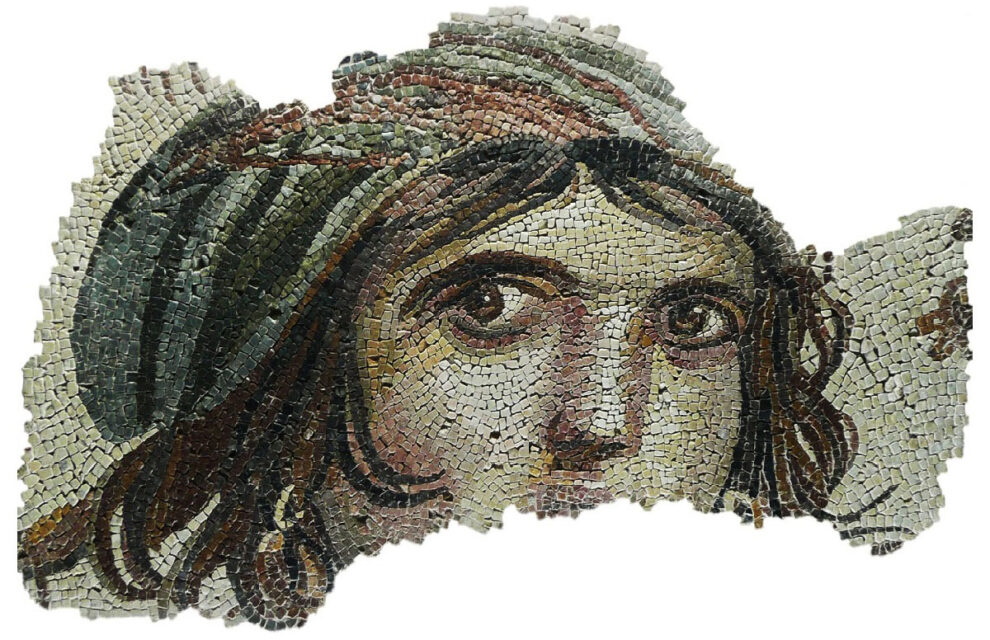

For me, the composite approach to scholarship is like a mosaic in Antiquity, hewn from multicoloured pebbles and pieces of marble. Consider the Gypsy Girl Mosaic of Zeugma in Anatolia, shown in the feature image at the top of this blog: this portrait of a maenad or female devotee of the god Bacchus is a 2000-year-old Hellenistic work. According to Stephanie Langin-Hooper, S. Rebecca Martin and Mehmet Önal: “She is oriented to the viewer’s right, although her large brown eyes stare directly out at the viewer. She has a full face with a narrow forehead and protruding cheekbones. A blue and black sakkos is wrapped around her long brown hair, beneath which are visible portions of two white and brown hoop earrings with round pendants. Her thick hair parts in the middle, curls falling onto the forehead and one cheek. Loose ends escape from below and fly over the front of the sakkos. She has bold black eyebrows and a straight nose. The lower part of her face was destroyed below the full upper lip. A thick brown line, surely part of the vine motif, intertwines with her hair and leads off the edge of the fragment at lower left. Part of what seems to be a flower is seen to the right of the mask.”

An amazing work of art in an ancient city in Turkey!

The whole picture of the mosaic is by no means contained or implied in each well-hewn pebble. A mosaic is not simply the sum of its parts, like in William Blake’s poem Auguries of Innocence: “To see a World in a Grain of Sand / And a Heaven in a Wild Flower / Hold Infinity in the palm of your hand / And Eternity in an hour.” Universes of meaning are not contained in each fragment of the mosaic.

In what way does the composite approach to scholarship resemble a mosaic? The composite approach is a creation based on fragments, chosen for their colour, texture and durability; these fragments are then “chiselled” by the scholar to fit into patterns, chosen and shaped for their evocative and dramatic power, and cemented together to form an original new work, which we take as a representation of something else.

The problem when scholarship resembles a mosaic? What works in the realm of art does not work so well in the realm of abstract ideas. A problem I see with the composite approach to scholarship is narrative distortion: the narrator yanks quotes out of context and then fits them into his or her own patterns of thought. I say this, having produced many documentaries which are like mosaics of meaning.

The composite approach to scholarship has sometimes been called “scissors and paste” history, for example by R. G. Collingwood, who notes this was the preferred approach during ancient and medieval times – it fact it was the only approach then known to historians. He writes: “There is a kind of history which depends altogether upon the testimony of authorities…. History constructed by excerpting and combining the testimonies of different authorities I call scissors-and-paste history. I repeat that it is not really history at all, because it does not satisfy the necessary conditions of science ; but until lately it was the only kind of history in existence, and a great deal of the history people are still reading to-day, and even a good deal of what people are still writing, belongs to this type.”

I feel uncomfortable about the composite approach to scholarship because of my training as a historian and biographer. This approach may be acceptable to philosophers, but it is unhistorical. After all, Taylor’s habit of quoting some intriguing feature of Nietzsche’s thinking, while neglecting to mention he was a proto-fascist, mysogynist, anti-Semite and, by 1887, a self-proclaimed nihilist, strikes me as unhistorical. (Taylor even seems to deny Nietzsche was a nihilist, on p. 60 of The Ethics of Authenticity: Nietzsche “used the term nihilism to designate something he rejected.”) Rather than seeing Nietzsche as the generator of ideas in the abstract, I would prefer a work that studies Nietzsche historically, alone, on his own terms, in the context of his own life and times.

A mosaic is a likeness that tells a story; the way the pieces are shaped says more about the intentions of the artist than of the raw materials themselves. Frankly, I love mosaics.

Composite scholarship – scissors and paste philosophy – is no less an invention, but in leaping from the decontextualized ideas of one authority to another, on the shoulders of giants, it risks falling short.

(On the other hand, Charles Taylor’s work Sources of the Self (Harvard University Press, 1989) is truly a work of genius.)