I have devoted some of my professional life to studying power.

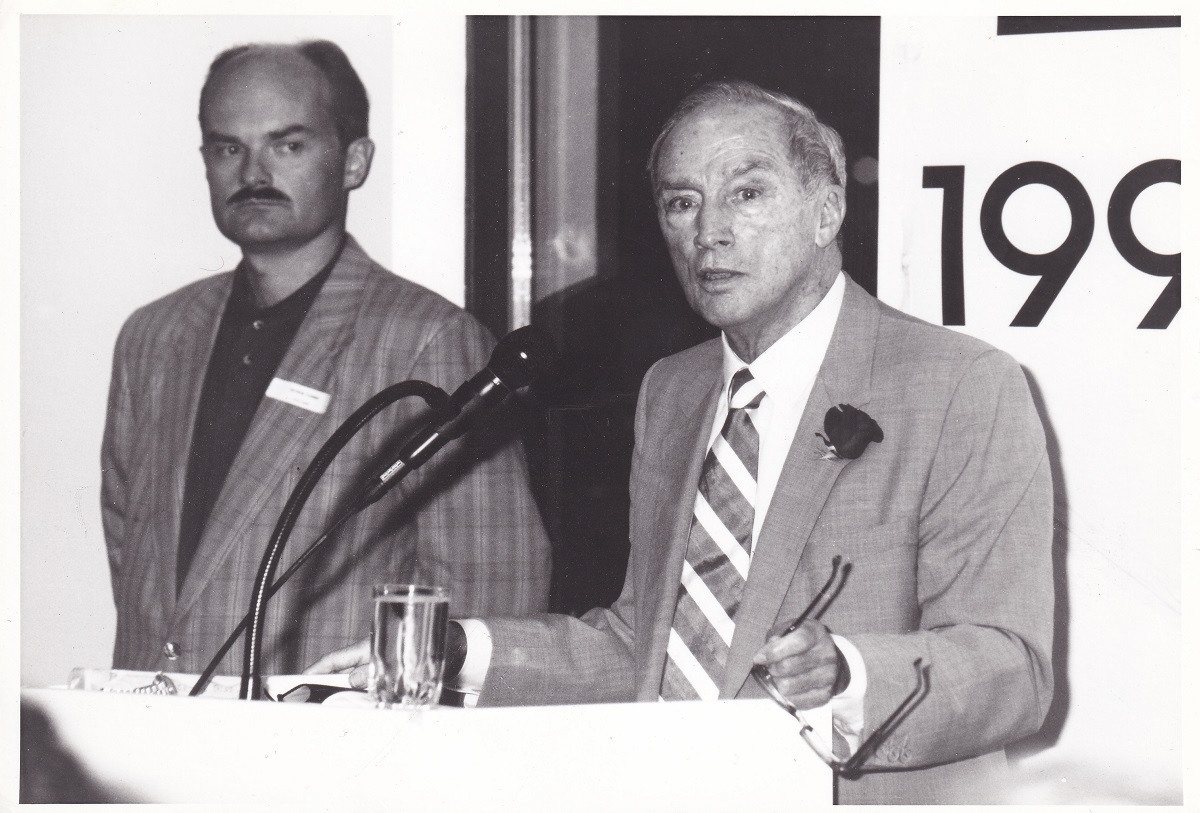

For example, in October 1992, I served as master of ceremonies the evening former Canadian prime minister Pierre Trudeau astonished everyone with a single-minded demolition of the Charlottetown constitutional reform proposal at the Maison Egg Roll, a Chinese restaurant in a working-class district of Montreal.

That evening, I saw first-hand what it means when someone fearlessly uses the power of words before an ambivalent audience, which he is determined to win over. I disagreed with much of what he said. His whole speech came as a defence of his personal legacy, as if he equated himself with Canada. But I acknowledge the impact – the power – of his eloquence, which followed the rules of classical rhetoric, contained a few colourful literary references, combined appeals to the emotion as much as the intellect, ultimately delivering a message about federal power and individual rights going right to the jugular of his political opponents.

In just 48 hours, I translated the speech and Q&A period afterwards (including comments from people who disagreed with Mr. Trudeau). Coming to 76 pages, this was my first book translation. It was clear to me Mr. Trudeau had written out his speech in advance, and memorized it. He just loved listening to the sound of his own voice.

Over the next few years, I remember interviewing Henry Kissinger and John Kenneth Galbraith, a succession of Canadian prime ministers, Quebec premiers, high-level British, French and American politicians, billionaire tycoons and a Middle Eastern warlord. Along the way, I got to know the head of a major Irish crime family. All of these people had an intimate understanding of power, although their methods and objectives were different.

And of course, two decades as a journalist taught me about the power of the media to reveal as much as to conceal.

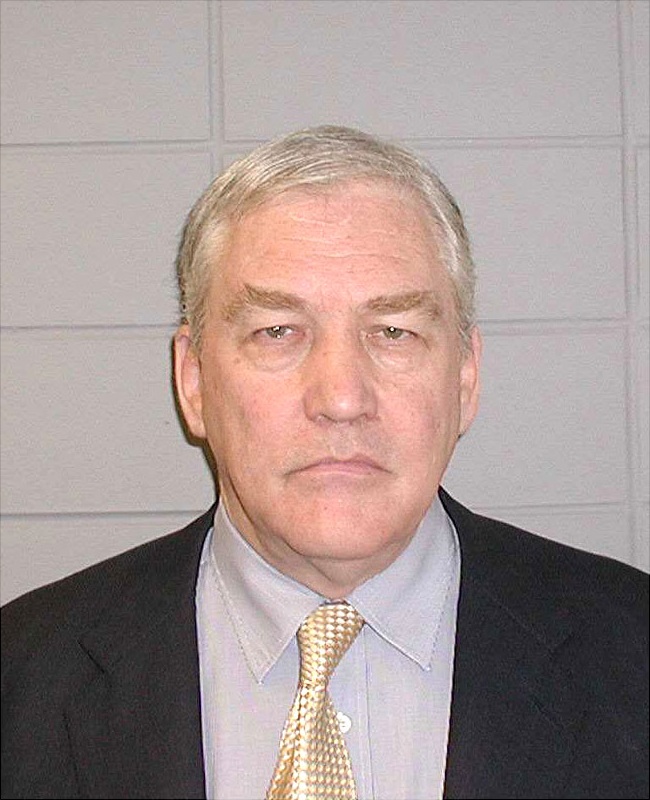

Then again, in writing Robber Baron, an unauthorized biography of fallen press baron Conrad Black which came out shortly after his criminal conviction in 2007, I was struck how deluded Mr. Black seemed during interviews with me, when he waxed poetic about his own understanding of power, quoting Machiavelli, Darwin, Nietzsche and Spengler. I wondered: if he really understood power so well, how could he end up behind bars at Coleman Low, where he was better known as Inmate No. 18330-424? Was it because he had surrounded himself with yes men who had never dared challenge him?

More recently, in following the ongoing constitutional disasters in the United States and the United Kingdom, I realize we are caught up with the concept of tyrannies warring against democracies.

Political power is less something one individual wields, tyrannically – whether Donald Trump or Boris Johnson – and more a matrix or complex of relations involving large numbers of insiders who are privy to information and advantages unavailable to other people.

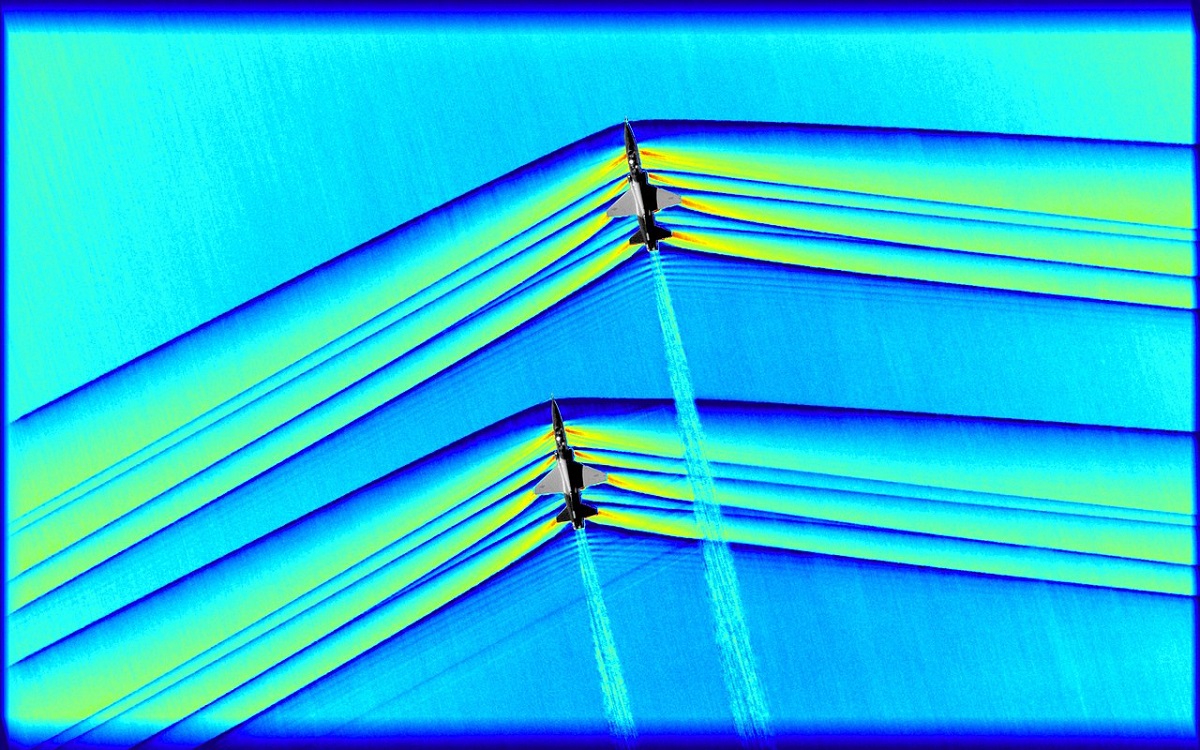

The power matrix is something like a power grid, distributing electricity back and forth. It generally has a lead insider, at the centre, and a network of lesser insiders, in supporting roles, branching out in all directions.

The matrix distributes power, in a regular flow. But the matrix exists to shield insiders and their leader from threats, while divvying up advantages and opportunities among a shadowy, tightly-controlled like-minded community. And these advantages, we have learned, may be financial, social and even sexual.

Examples are: influence peddling (selling access), kickbacks for government financing, skimming public funds, collecting finder’s fees, drafting laws and regulations specially (and secretly) for the benefit of particular companies, granting golden parachutes to politicians once they leave office (for services rendered while they were in office), and illegal financing of political parties – all very pervasive practices in Western democracies. Once a political party or government accepts illegal financing, it becomes vulnerable by offering leverage to interest groups or individuals behind the scenes. Each insider in the matrix is well aware how much is at stake, because at every moment the web of interests in the matrix is targeted by political opponents and other outsiders.

When insiders act like yes men, they are above all saying yes to their share of power. They are more concerned with maintaining the matrix and their part in it than with the legality of their actions in the name of the matrix or the impact of those actions on outsiders – anyone beyond the matrix. Problems are perceived as shock waves exerted on the matrix.

Lawyers, fixers, bullies and cleaners can always be called on, to scrub incriminating scenes and keep serious problems out of sight. Many people within the matrix are in the know. Many are therefore complicit. Obstruction is the name of the game.

This is why I find public discourse about liberty and democracy in the Western world out of whack nowadays.

On the one hand, the electorate expects to see values in action … or at least actions driven by values they agreed upon and voted for. The electorate boots out one party, weakening the power matrix in place. In so doing, the electorate chooses another political agenda, delegating power to a second party poised to launch a new matrix of its own.

On the other hand, insiders maintaining the power matrix are working day and night to pursue their own private interests and agendas, while making it seem those agendas are actually in the public interest. Which is why we hear so frequently nowadays about conflicts of interest in governmental circles.

Public virtues don’t often coincide with private vices. The gap between the two is opening wider these days. Here again, public discourse is out of whack. In polarized situations, partisans only find fault with the opposite camp: they turn a blind eye to conflicts of interests within their own power matrix. They treat corruption within a matrix as a purely partisan issue: Liberal vs. Conservative, Canadian federalist vs. Quebec separatist, Democrat vs. Republican.

And yet…. at a certain point, even the most elaborately-structured power matrix comes tumbling down to the ground, under the impact of shock waves, or the forces of gravity.

To use an analogy: I remember the ice storm in Montreal in January 1998, when two weeks of freezing rain led to the collapse of the electrical power grid in southern Quebec. I was without electricity at home for three weeks.

There comes a point where power matrices collapse like hydro-electric pylons under a thick coating of ice. They are vulnerable. They can no longer be sustained. It makes for a nasty spectacle. Things can end so suddenly in the political world.