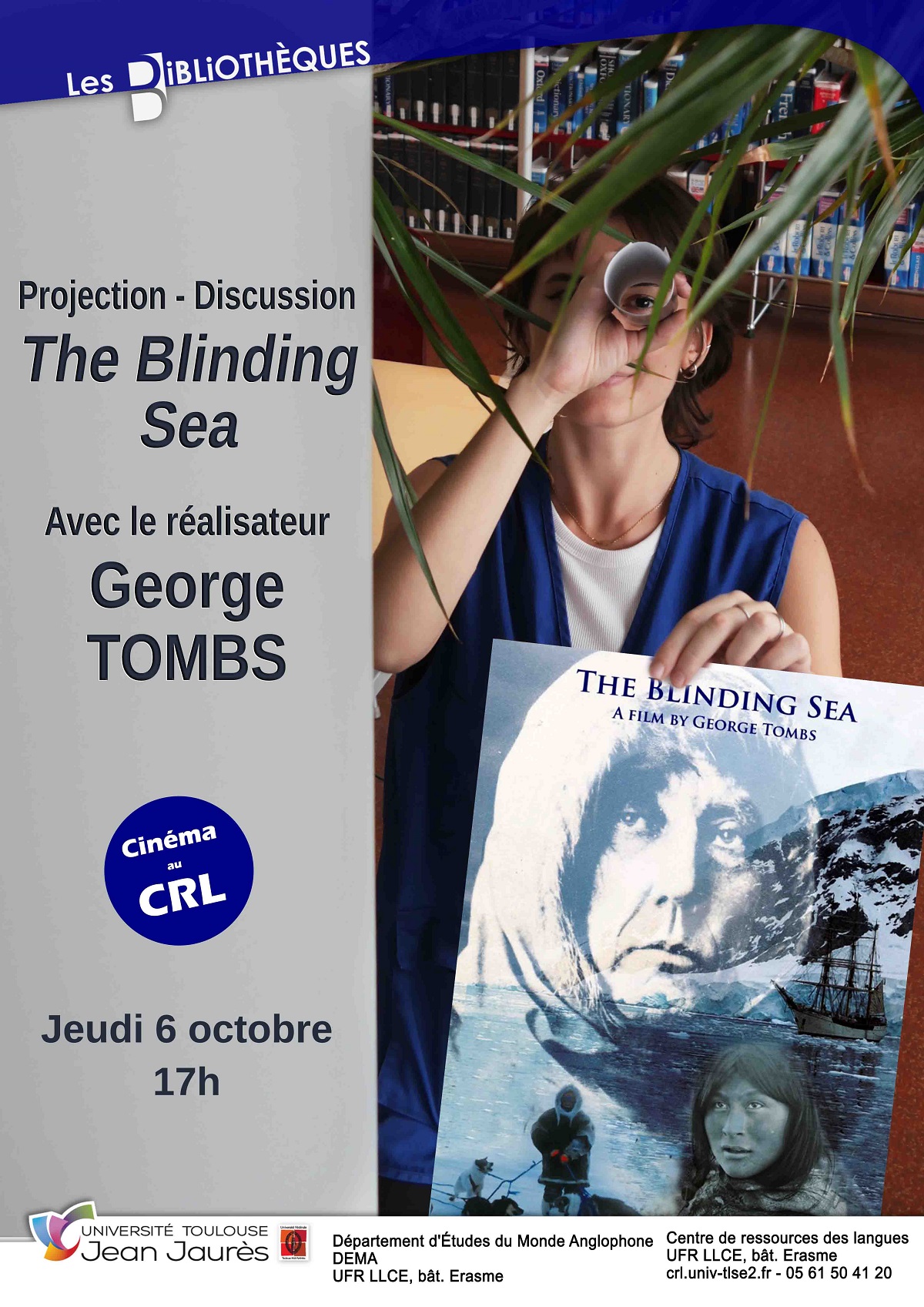

I just presented The Blinding Sea at the Université Toulouse Jean Jaurès, in southern France. This was the second time the film has been shown in this city. Professor Corinne Bigot, who specializes in Anglophone Studies, Commonwealth Literature and Canadian Studies, as well as her colleagues Myriam Yakoubi and Zachary Baque, had already seen the film last April, at the Toulouse Business School, a private institution. They made a point of inviting me back a second time.

We met in the library of the Centre de ressources des langues (Language Resources Centre). This library is unusual in that talking is encouraged (after all, students need to practice the languages they are studying)!

We watched the film together. The audience was particularly interested in Roald Amundsen’s interactions with the Inuit of Arctic Canada. During my presentation, I set the story in the context of Norwegian, British, southern Canadian and Inuit culture a century and more ago. I explained that Amundsen had no imperial or colonial ambitions in spending two years learning from Inuit, and he made no attempt to exploit Inuit. On the contrary, he interacted freely and respectfully with them, and learned from both Inuit women and men about the best polar techniques for healthy eating, building shelter, dressing properly to withstand the extreme cold and wind, and of course how to travel long distances by dog-team.

Myriam Yakoubi spoke about the Hudson’s Bay Company and its role in exploiting natural and human resources in northern Canada. Since she specializes in British imperialism in the Middle East in the early 20th century, particularly in Iraq and Jordan, she is well aware of the impact of the imperial mindset on subject peoples. She also spoke about the important role of women in transmitting knowledge, everywhere in the world.

I mentioned that Canada is not often considered to have colonized its enormous landmass. Colonialism is generally considered to consist in a metropolis, often in Europe, controlling far-distant colonies on another continent. However, as a journalist in the 1980s and 1990s, I reported on Canadian colonialism first-hand. I covered the forced relocations (deportations) of Inuit communities as well as the harrowing experience of an Inuk woman in a Quebec residential school, at a time when Canadian mass media were reluctant to report on the cultural genocide to which Aboriginal people were so obviously being subjected.

I also reported on the land claims process in the 1980s, the rise and fall of industrial projects, and the extraordinary push towards the creation of the Nunavut territory in 1999, which has given Inuit a real measure of power over their own destiny, as well as the tundra and sea where they have lived for thousands of years.

With The Blinding Sea I have wanted to pay tribute to the originality of Inuit knowledge, showing the mutual respect they and Amundsen showed one another, and also the vitally important role Inuit have played in the exploration of the circumpolar world.

This gives a particular flavour to the film. In European exploration narratives from a century and more ago, Aboriginal people often remained faceless, and were rarely named. For his part, Amundsen was willing and able to enter into the subjective world of the Inuit, to learn their language as best he could, to name each Inuk who had helped him during his two-year stay with Inuit, and to understand how Inuit investigated Nature in their own evidence-based way. This taught him that their tacit knowledge system was in many ways superior to what passed for science at the time. Amundsen was sometimes subject to sudden shifts in mood and strategy; he could act in a tactless and even heartless way. And yet he also had empathy.

The Blinding Sea is a work of research, but it is also a work of art, combining rigorous documentation, interviews with people directly related to the story, original cinematography on location, textured soundscapes all the way through, voyages at sea, journeys by dog-team, flights over glaciers and snow-capped mountains. I am working on an expedition biography of Amundsen, to be called WildTrekker, as well as articles in journals and magazines around the world.

Sharing the film with the audience at the Université Toulouse Jean Jaurès comes as such a thrill. Thanks so much to Corinne Bigot, Myriam Yakoubi and Zachary Baque for inviting me. À la prochaine!