While shooting The Blinding Sea, I flew in a Cessna 205 prop plane over the Kaskawulsh and other glaciers in the Yukon Territory, and I use this footage as a stand-in for glaciers in Norway and Antarctica. To get better shots, I opened up the little rectangular window next to me, and stuck my camera through it, into the howling March wind. (See my feature photo, above.) The air temperature at 10,000 feet that day was -30°C; our speed was 145 knots; according to the wind chill calculator at NOAA, the wind chill was therefore -62°C. Bad enough to get serious frost nip, so I had to be careful.

I remember thinking at the time: polar expeditions take a lot of preparation – you don’t just start acquiring knowledge once you get there. If someone parachuted me onto the glacier above, especially in winter, this would come as a death sentence to me. The polar environment is unforgiving, so knowing how to live there takes a lot of knowledge.

After a screening last year at the Université Grenoble Alpes, I discussed the film at length with Sir Muir Gray, to validate some of my thinking – once the film was completed. He is a Professor of Surgery at Oxford University and co-founder of Evidence-Based Medicine and Evidence-Based Healthcare. I got to know Muir initially when running a medical research association. I then did a postgraduate year in Medical Sciences at Oxford, where he lives, so we got to meet up again periodically.

A lot of research went into making this film: I was guided by intuition much of the time, whether in the direction my research took, or in the craft of film-making itself, as I brought together many different strands of the story as well as video, still images, interviews, textured soundscapes and music. This discussion with Muir helped me better understand the film!

Many polar biographies read like Comic Book History – tales of adventure and heroism at the ends of the Earth. They place the accent on rivalries whether personal or national, and they moralize after the fact about what, surely, ought to have been done, from the comfort of an armchair, with hindsight.

Polar biographers also have cultural limitations. Many English-speaking biographers cannot read French, so they are unable to understand the importance for Amundsen of the Belgica expedition; few polar biographers have a background in health sciences; fewer still have bothered to get to know the Inuit. In validating knowledge during the research phase for the film, I even came across self-anointed “polar experts” who had never been to the polar regions.

In discussing the film with Muir, I asked whether I am right in presenting a ship’s crew as large and contained enough to be considered a community or population from the public health point of view? Muir said yes, this was very important.

I asked whether Amundsen’s venture to the South Pole can be seen as an example of knowledge translation? What if the best evidence comes out of another (i.e. Inuit) knowledge paradigm, and is not even written down? Muir said a distinction should be drawn between tacit and explicit knowledge in healthcare, both of which furnish evidence. Tacit knowledge is practical and subjective, is rarely published and may sometimes not even be written down. Tacit knowledge states how to do it. Amundsen painstakingly acquired tacit knowledge from the Inuit. Explicit knowledge, meanwhile, is created by researchers and is published in scientific journals. It states what to do.

This distinction reminded me of Michael Polanyi’s work The Tacit Dimension, according to which we can know more than we can tell.

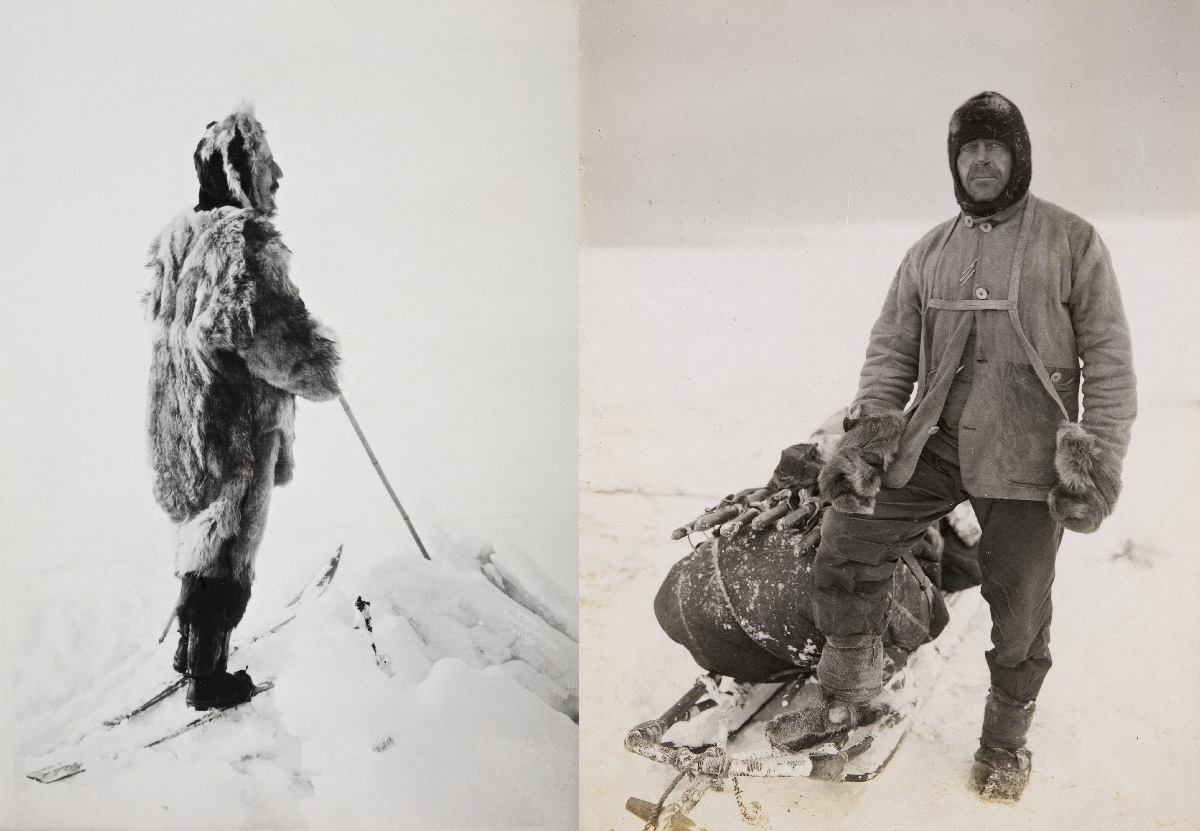

Tacit knowledge, experience and knowledge translation played a huge part in Amundsen’s polar career – not only in building up his knowledge base during the two-year apprenticeship with Inuit in Nunavut, then applying it, but also in remaining silent (tacit) about his plans to head for the South Pole, whereas Robert Falcon Scott made everything as explicit as possible. Of course, Amundsen also acquired explicit knowledge, studying all polar exploration narratives he could lay his hands on, and drawing on Norwegian knowledge of polar travel and how to avoid scurvy. For example, in the early 1890s, Amundsen studied medicine at the Royal Norwegian Frederick University of Christiania (modern-day Oslo), and this period is often written off by biographers as a waste of time, during which he learned nothing. It is interesting to note one of the professors of medicine there was Axel Holst, a pioneering researcher on scurvy, who correctly understood scurvy is a deficiency disease, although Vitamin C was only discovered in 1912 and isolated in 1928. Amundsen and Holst tacitly held the same positions on nutrition.

I asked Muir if I was correct in the medical interpretation I give of the cumulative effects on Scott and his remaining crew-members of malnutrition, hunger, frostbite, gangrene, scurvy, etc? Muir said yes, this interpretation is correct. I asked whether the body “shuts down” as it approaches death, one bodily function after another? Yes again, he said. Even if Scott had been found while still alive, I said, he was 260 km. from the base camp, and might have needed amputations due to gangrene. It would have taken 10-15 days, at best, to haul him back. Would he have survived long enough in -40°C weather? Would he have survived amputations without antiseptics? Muir said that Scott and his remaining crew-members would have been very unlikely to survive in these conditions without antiseptics.

If we take Scott out of the noble/brave/honourable mode and ask what he lived as a person, I said, then he was subject to unbelievable suffering, imposed on him by a system that just couldn’t learn, and that drove men to harrowing avoidable death. Yes certainly, said Muir. Stress, combined with Scott’s inactivity would increase inflammation; starvation would lead to metabolic trauma; by the time he and his remaining two companions sheltered for nine days in their tent, in March 1912, they were past the point of recovery.

Finally, I asked Muir whether Edward Atkinson, the expedition surgeon who found Scott’s remains on November 12, 1912, could have told, simply by looking at Scott’s desiccated and mummified body, whether he had suffered from scurvy? Muir said that at that point, Atkinson could not tell at all, given the scarring and discoloration of tissue.

To come back to the anecdote at the beginning of this blog, about flying in a Cessna over glaciers in Kluane National Park. Amundsen and his crew spent close to a decade, preparing rigorously for their South Pole expedition. Scott and his remaining companions give me the impression they were parachuted onto the Antarctica Plateau, without adequate preparation. Man-hauling on starvation rations, at such a high altitude, so late in the season, with no safety margins, came as a death sentence.