I remember attending a Montreal meeting of the Fédération professionnelle des journalistes du Québec, around 1990 or so. The French journalist and author Jean-Paul Kauffmann came to thank us (I was a member of the FPJQ), for having pushed for his release as a hostage. He had previously lived in Quebec.

He told us how he was kidnapped by Hezbollah in 1985, on the way to the Beirut airport with sociologist Michel Seurat. They were held at first in an underground garage, and always forced to cover their eyes in the presence of captors, who would sadistically load and unload their automatic weapons nearby. They were transported in the trunk of a car, then forced into a metal box on a rooftop in Beirut while the city was under bombardment. His cellmate Michel Seurat died, apparently of cancer, seven months after the kidnapping.

While in captivity as a hostage, occasionally shunted from one place to another, rolled up in an Oriental carpet, or transported in a coffin, Jean-Paul Kauffmann had to work hard to maintain a sense of self. Who was the captor? Who was the captive? What did solitude do to you? He was eventually transferred to a Shi’ite family with young children in Sidon, where conditions improved.

In 1988, an article in the New York Times reported on his release from arbitrary captivity:

“‘We survived,’ Jean-Paul Kauffmann said today of his three years as a hostage in Lebanon. ‘We did not live.’ Dressed in fur-lined air force jackets, Mr. Kauffmann and two other freed hostages, Marcel Carton and Marcel Fontaine, stepped off a small jet to a somber reception at Villacoublay, an air base southwest of Paris.

“Greeting them were other former hostages, Prime Minister Jacques Chirac, Cabinet officials, army officers and a restricted number of journalists. Interior Minister Charles Pasqua, who oversaw the negotiations for their release, had joined them during a stop in Corsica.”

I went to talk to Jean-Paul Kauffmann after the Montreal meeting. His eyes were so tired, as if he were weighed down by the sufferings of the universe. He had come very close to becoming anonymous, an object, a non-person. But after his liberation, he risked being saddled with a new and unwelcome identity: people remembering him solely as a former hostage. He was now a spectacular other, with tales to tell. Curious people would gawk at him, and swing between almost envying the adventures he had lived through, and the urge to deny there could be any truth to it.

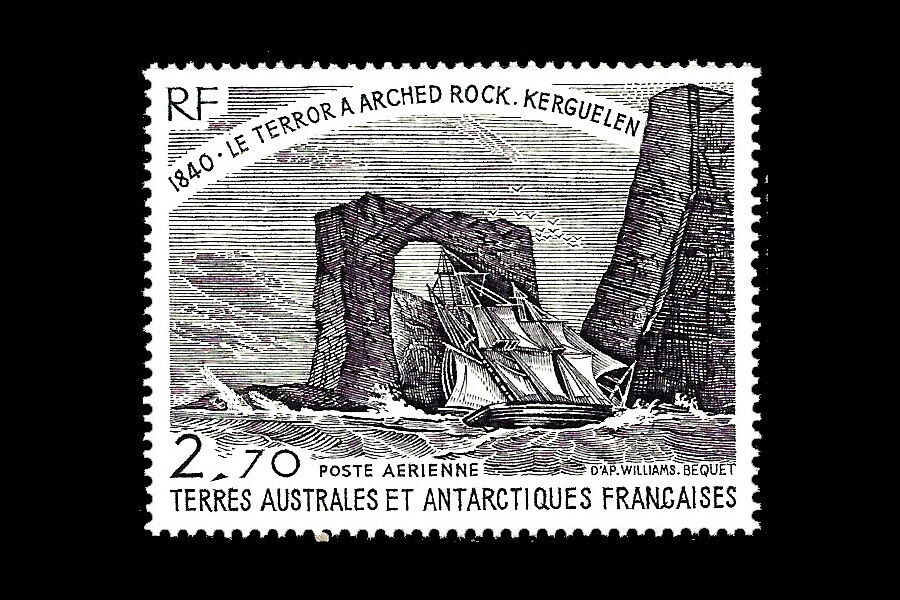

I have read several books of Jean-Paul Kauffmann’s since this time, and feel a sense of utter futility as he recounts his lonely quest to find the (fallen) Kerguelen Arch, and Napoleon’s exile on St. Helena, and journeys to nowhere else.

But one thing in particular struck me in the address he gave us in Montreal. And it has become a life lesson for me.

One sentence, actually, which I remember as: “vous êtes une victime lorsque vous vous laissez interpréter par les autres” … which can be translated into English as “you are a victim when you allow yourself to be interpreted by other people.”

There is a lot of wisdom in this short sentence.